Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Monday, 14 June 2021 00:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Since the pandemic has brought in far-reaching social, political, cultural, and economic impacts on affected countries, the bank regulators cannot remain in a closed silo displaying obliviousness to these changes

Excerpts of a presentation made before the English Language Club of the Bangladesh Bank

A new normal code for human behaviour

A new normal code for human behaviour

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in several waves in almost all the countries in the world has codified a new normal for human behaviour. This code of relationships entailing social distancing, wearing face masks plus face shields, frequent hand washing, and keeping a record of first-hand contacts for later follow-up is going to stay with the world for several years.

It has also changed the approach which bank supervisors and regulators should adopt when dealing with banks under their charge to ensure stable financial institutions and systems. Since the pandemic has brought in far-reaching social, political, cultural, and economic impacts on affected countries, the bank regulators cannot remain in a closed silo displaying obliviousness to these changes.

The complete lockdown of the countries

To prevent the spread of the pandemic, the standard tool used by authorities had been a complete lockdown of the countries for prolonged periods. That was a necessity because the virus was transmitted from person to person via human contacts. To keep it under check, all human contacts had to be kept at a minimum. China, the epicentre of the pandemic, demonstrated its success by preventing people in the affected regions from even moving out of their homes.

It was a draconian measure but considered essential because of the extremely high cost which the pandemic inflicted on human lives. When it comes to choosing between life and any other thing, modern societies always go for the former since life is considered invaluable. But the prolonged lockdowns disrupted a significant part of economic activities involving production and distribution.

Need for reviving battered economies

It caused economies to move down from their normal growth paths generating in most cases a shrinkage of the total output accompanied by an increase in unemployment. Thus, an urgent requirement that arose was the need for reviving the affected economies. The full burden of this revival devolved on the governments which could through their sovereign powers mobilise resources for this. But there were two issues which had handicapped the governments in performing this job.

One was that some governments did not have a sufficient budgetary leeway to undertake a massive expenditure program due to high budget deficits, committed expenditure for maintaining public services, and meeting debt servicing commitments. The Government of Sri Lanka is a case in point.

The other handicap was the shrinkage of the tax base due to the shrinkage the economies involved and inability of tax authorities to reach out to taxpayers due to economic lockdowns. As a result, there was a resource constraint for many governments. This was to be filled by getting the central banks to print new money and relax their monetary policy stances. Thus, in the final analysis, the actual burden of reviving the economies have fallen on central banks.

Central banks’ new challenge

Central banks throughout the globe have risen to this new challenge with a host of measures. In the first place, they have resorted to the main weapon they are having, namely, the ability to print money. Using this weapon, they have funded the governments to finance their cash deficits and provided liquidity to the economic system through specially established refinance windows.

A central bank would be cautious to use this weapon in normal situations. That is because it would derail their monetary policy targets by increasing reserve money and through that increase, the final money supply in multiple terms. That is because commercial banks are able to create new money by using this reserve money as seeds, based on the size of the money multiplier in the system.

In Sri Lanka, the money multiplier stands at about 10 at present and hence, every rupee created by the central bank as reserve money will eventually increase the money supply by about 10 rupees. Since economic growth is either negative or low due to the pandemic, such an increase in the final money supply will put pressure for prices to rise. But the present pandemic has forced central banks to revisit their monetary policy objectives.

A central bank normally goes by the notion that inflation is the public enemy number one. But the pandemic has obliterated this because the public enemy number one now is the loss of human life. If life is not saved, there is no purpose of controlling inflation. This is in fact re-prioritising the policy objectives considering the specific dangers faced by respective countries.

Policy stimulus introduced by central banks

The other policy measures taken by central banks to support economic revival are maintaining low interest rate regimes, promoting private sector credit expansion, and extending loan moratoria to borrowers affected by the economic downturn due to the outbreak of the pandemic. The objectives of the first two measures are increasing investment, stimulating the economy, promoting economic activities, and generating employment. The last measure, namely, extending loan moratoria, will help businesses to survive through the difficult time periods and commence their business activities once the system has returned to normalcy. What this means is that banks have been forced to bear the full burden of the economic revival.

Problems of bank regulators

Problems of bank regulators

These measures are supportive of economic activities, but they create problems for bank regulators. That is because they require banks to relax their normal loan sanctioning conditions, and thereby, accommodate even unviable customers. The corollary of this free attitude is the elevation of the non-performing loans – loans that are not repaid on time – eventually. It would erode the capital bases of banks. Since bringing new capital is a remote possibility under the pandemic situation, regulators would be faced with a situation in which most banks are distressed and needing support. In the case of state banks, due to the fiscal constraints, the governments are unable to recapitalise them, as necessary. They cannot raise new capital from the capital markets due to objections of employee unions and parties which are opposed to privatising state banks. When a few of systemically important banks are distressed in this manner, bankers are like people sitting on a volcano that might erupt at any time with far-reaching consequences. Banking regulators cannot, and should not, tolerate this.

Balancing economic revival and financial system stability

This is a challenging task requiring bank regulators to strike a proper balance between economic recovery and avoidance of distressed banks. There is no predetermined set of guidelines for them to follow. A pragmatic approach is to give priority to economic revival, while keeping a watchful eye on developments in individual banks. There, the challenge faced by them is to resolve the conflict between the two regulatory approaches they normally follow, namely, the micro-prudential regulation and macroprudential regulation.

Protecting the system or protecting the banks?

In normal situations, these two approaches conflict with each other. Bank regulators are mandated by their legislations to maintain the financial system stability and not the stability of individual financial institutions. However much a regulator is competent, it is impossible for him to protect every financial institution in the country. That is because they are not homogeneous, and differ significantly from each other with respect to capital base, management competency, risk appetite, specific market conditions, etc.

Hence, when one bank may do well, another may fail. The failing bank, if it cannot be recovered, is like a parasite that must be removed to save the main body of the financial system. Thus, the regulators are concerned about individual banks only to the extent they are systemically important, and their failure would damage the whole financial system.

This aspect of protecting individual banks comes under micro-prudential regulation and it directly conflicts with macroprudential regulations.

Since the stimulus packages introduced by central banks to fight the pandemic might propel bank failures, regulators are now required to pay attention micro-prudential regulation as well. Hence, while the financial system is kept under a watchful eye, regulators must be more concerned about the performance of individual financial institutions in this pandemic situation.

Onsite examinations becoming defective

Regulators use two tools to keep individual banks under their watchful eye. One is the examination of their books and accounts periodically by visiting bank offices, known as onsite examinations.

The other is a remote-control measure under which banks’ detailed data are continuously assessed under a system called offsite examinations.

The onsite becomes ineffective under the New Normal Codes of the pandemic situation because, visiting examiners are required to maintain social distancing, wear face masks and face shields, wash hands frequently and keep a record of the people whom they have come to contact while visiting the place. These cumbersome chores do not permit visiting examiners to do a thorough job.

Banks, when they know that examiners cannot do a thorough job, have incentives to misrepresent the facts that cannot be discovered early. Because of this defect of onsite examinations, regulators should strengthen the offsite examinations with a new approach. That new approach is the digital monitoring of banks by connecting them in real time to the ICT system of the regulators.

Need for digital monitoring

In this digital monitoring system, regulators should establish early warning triggers of emerging distresses in banks. This will move regulators from past-looking or post-mortem examinations to forward looking or future oriented examinations.

The present system is a post-mortem examination because the bank regulators examine past data and make judgments about the bank concerned based on them. The past is not even a good guidance for the present, let alone for the future.

That is because systems are fast changing, on one side, and subject to unexpected external and internal shocks frequently, on the other.

This was evident from both the Asian financial crisis of 1997-8 and the global financial crisis of 2007-8. No banking specialist was able to predict them accurately because the good past data had blinded them totally. In this sense, the COVID-19 pandemic which has forced regulators to move for forward-looking monitoring of banks can be regarded as an unintended blessing.

Early Warning Indicators

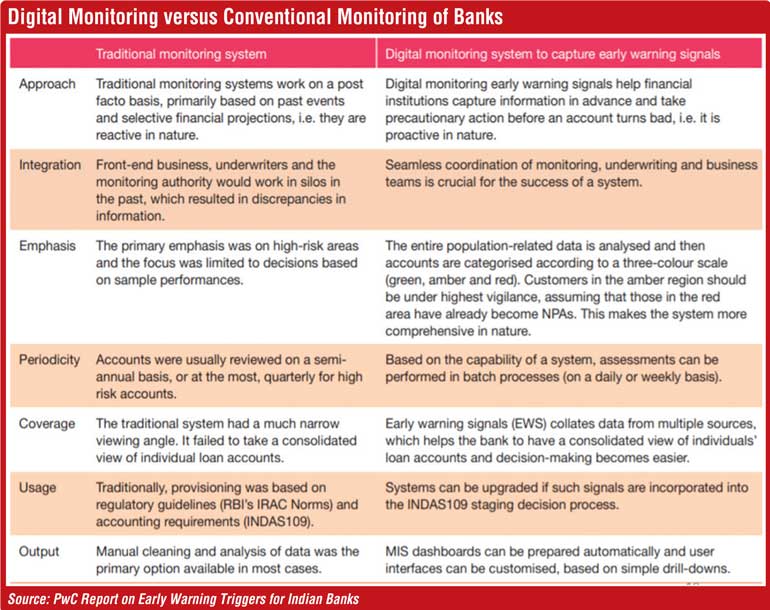

The Early Warning Indicators or EWIs which PwC has designed for Indian banks in a digital era comes handy for bank regulators desirous of introducing digital monitoring of banks (available at: https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/consulting/financial-risk-and-regulations/early-warning-signals-in-a-digital-era.pdf ). Table 1 extracted from the PwC report highlights the difference between the conventional monitoring and digital monitoring with respect to some key parameters. They are the approach, integration, emphasis, periodicity, coverage, usage, and output.

The approach is moving from the past as done in conventional monitoring to the future. Hence, it is not a post-mortem examination but a future projection. In the conventional monitoring, key players and the regulators work in separate silos resulting in the discrepancies in the information flow. But in the digital monitoring, all these key players are connected digitally and, hence, are able to know of developments on a real time basis. The conventional monitoring is based on sample analyses covering only key risk areas.

But the digital monitoring enables the regulators to look at the entire data set, known as big data, and use numerous apps available to analyse them instantaneously.

The conventional monitoring is periodic, maybe quarterly or half-yearly, but the digital monitoring that gives regulators access to data in real time can be done immediately. As against the conventional monitoring, the coverage of the digital monitoring is the entire population.

Digital monitoring will also enable regulators to use the data very widely.

The output in conventional monitoring was done manually but in the digital monitoring it is arrived at by using advanced management information systems. Given these advantages and the specific problems created by the COVID-19 pandemic, it behoves both banks and regulators to move to digital monitoring as a priority. But it requires both banks and regulators to get connected to each other digitally.

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the rules under which both banks and regulators should play the game. But it has forced the regulators to move into the future rather than playing with the past. That is an unintended blessing which the COVID-19 pandemic has brought in to the banking sector.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)