Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 8 September 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Pakistan Army is a paradox. On the one hand, it is a professional outfit run along professional and ‘bureaucratic’ lines. But on the other, it is a highly politicised organisation in as much as it exercises decisive control over Pakistan’s political system whether it is in the seat of power as a result of a coup or it is in the barracks with civilians holding the reins of power.

“This is a highly ‘professional’ army in some respects, and remarkably ‘unprofessional’ in yet others. The very same individuals perform both its military – technical and political – interventionist activities,” say Paul Staniland, Adnan Naseemmullah and Ahsan Butt in their recent paper entitled ‘Pakistan’s Military Elite’ (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402390.2018.1497487?scroll=top&needAccess=true&).

This is achieved by the fusion of internal bureaucratic discipline with placement of recently retired elites in positions of civilian power, the authors say. The accent is on ‘recently retired officers’ because their ties with the military are the closest. They can be counted on to promote the army’s interest in the civilian institutions they are working in.

The Pakistan army is thus different from armies of many other countries, especially the Western democracies, where the army is not only under tight civilian control but is in no way involved in exercising any civilian authority.

Sure, the Pakistan army has been in and out of power. But it has never ceased to count politically. It has always seen that the ‘national interest’, as conceived by it, is served by civilian governments. A recalcitrant government would be overthrown.

Bureaucratic institution

Staniland and his colleagues say that there is “strong evidence of high levels of bureaucratic institutionalisation and professionalism within the Pakistan Army.”

“The rules within the organisation seem to be generally followed, with limited factionalism and consistent promotion pathways. There is a stark contrast between this cohesive, rational-bureaucratic organisation and other political militaries racked by internal fratricide, plagued by factional rivalries, or vulnerable to divide-and-rule strategies by ruling elites, like those in 1960s Nigeria, 1970s Bangladesh, or 1990s Indonesia.”

The Pakistan army’s image as a well organised, internally consistent and stable force is one of the sources of its political credibility and strength. In the midst of political chaos and infighting in Pakistan, the army stands out as a unique institution, a model which other institutions will do well to follow.

This gives the army moral authority among Pakistanis. Though the people have, from time to time, rejected military regimes and struggled for civilian democratic rule, they have also not been averse to letting the army set the national house in order in times of chaos.

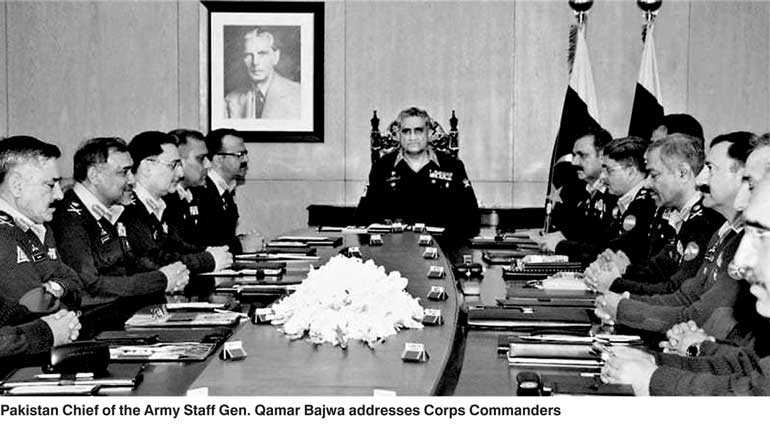

Corps Commanders

The Corps Commanders, headed by the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), constitute the core of the Pakistan army. It is this body which makes all the key decisions, both military and political. Its membership is not based on the Chief’s personal fancies but on bureaucratic principles.

The path to the post of Corps Commander is well laid out and traversed consistently as in a bureaucracy. The qualifications have changed with changing needs but the path to it is well set and predictable at any given time.

As a social group too, the Corps Commanders are well integrated. At the time of Staniland’s study, 55% were from Punjab and 21% from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). Only 3% were from Sindh, 3% from Kashmir, and 2% from Balochistan. Age-wise too, the Corps Commanders are a homogenous group largely between 54 and 58. They also retire more or less at the same time.

“The general clustering of the retirement age suggests an institutionalised organisation. In personalised or factionalised militaries, we would expect much higher variance, with favoured officers – the son-in-law of the dictator, members of the dominant faction – being promoted early and often,” Staniland points out.

The Corps Commanders have more or less the same service background. 66% are from the infantry, 15% from armour, 14 % from artillery, and less than 5 % from engineering or from air defence. This blend has not dramatically changed over time.

And the Pakistan army is basically an infantry army. Eight of 10 army chiefs came from the infantry. This reflects the composition of the Pakistan military as whole. Presently, the army has 25 divisions, of which 21 are infantry divisions.

Good retirement benefits

Good retirement benefits

A key reason for the stability of the institution at the top level is the assurance of good retirement benefits, the researchers say. Retired Generals and other senior officers are seamlessly accommodated in government institutions and in the many ‘Fauji’ or army-owned commercial enterprises such as Mari Gas, Fauji Fertiliser, Fauji Cement, Askari Cement and Askari Bank. Over 60% of Corps Commanders worked for the government immediately after retiring. Personnel in these positions change roughly every three years, providing opportunities for the newly retired.

The Fauji enterprises are owned by the Army Welfare Trust administered by the GHQ. But they are public limited companies listed in the stock exchange. They are as much part of the army structure as they are part of the civilian structure and represent the military-civilian linkage. Close and continuous involvement with civilian activities contribute to the army’s influence over civilian life.

“The placement of retired elites has not shifted much across periods of military and civilian rule since the late 1980s: Even when back in the barracks, the army has deep reach into the economy and bureaucracy,” the authors point out.

Land and housing

The Pakistan army is involved in acquisition of land both to provide retiring officers with residential property and to participate in the lucrative property market in Pakistan, the researchers say.

“Retired officers often own more than one property; the pyramidal structure of the Army is operative when it comes to land perks. After 15 years of service, officers are entitled to one residential plot, after 25 a second, after 28 a third, and after 32 a fourth.”

“Thus, selling or renting housing to civilians is a common practice, and military officers and civilians commingle in most of the ostensibly military housing companies, which have become some of the most elite locations in urban Pakistan

The stability the military system and its consistent and lucrative links with civilian Pakistan through commercial activities obviate the need for entering politics to make a living after retirement, the authors contend.

Education

Pakistan army lays great emphasis on the education of its officer cadre. Corps Commanders are either graduates or post graduates. Commandants of the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) and the Command and Staff College often become Corps Commanders. And this is increasingly so because the modern army needs leaders with skills other than those acquired on the battle field.

“Of the 54 officers who left service in or prior to 2000 about whom we have prior command data, 35% held a General Head Quarters (GHQ) staff position; 33% held a combat formation command, and 15% commanded an army school. By contrast, of the 96 retirees after 2000, GHQ positions accounted for 48% of pre-corps positions, heads of army schools for 16%, and a combat formation command for only 11%,” the paper says, showing the increasing importance being given to academic attainments post-2000.

The post-retirement jobs in the Fauji companies also need qualifications as these are commercial enterprises and answerable to shareholders.

Inter-Services Intelligence

Even the shadowy Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the main intelligence arm of the Pakistani State, is as bureaucratically organised as the rest of the military and is inextricably linked with the army structure. It is not a closed and autonomous unit as ISI officers enter from other units and exit to join combat or staff units.

Like the rest of the army, the ISI is also a Pashtun-Punjabi outfit. But the ISI commanding elite are more broadly spread across army units than the Corp Commanders: 41% are from the infantry, 23% from artillery, 18% from armour, and 18% from engineering or signals.