Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 23 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

An unfulfilled promise of reforming the tax system

In the first economic policy statement, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe made a number of pledges related to taxes and tax reforms. One was that the Government would review whether the tax concessions given to investors have really delivered the expected outcome. Instead of tax concessions, he promised to put in place a low tax regime which would be enjoyed by all investors, whether they were local or foreign.

Another was to improve the tax revenue of the Government commensurate with the increase in the country’s Gross Domestic Product or GDP. In the past, that ratio had fallen disappointingly from around 18% in 1980 to 10% in 2014.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe

A third was to change the tax structure from the current 80-20 shares in indirect and direct taxes. Since the indirect taxes place a bigger burden on the poor, the ratio would be changed to 60-40 so that the rich will pay more taxes. A fourth was to rationalise the tax policy by doing away with imposing taxes on past earnings. A fifth was to impose taxes only on income earned in Sri Lanka and not outside. Although these pronouncements were short of a comprehensive tax reform policy, they at least sought to address some of the burning issues in taxes.

In the subsequent policy statements made in October 2016 and also in October 2017, there was no mention about these tax reforms though there were references to reducing the budget deficit and the country’s debt levels. In the Vision 2015 released two months ago, the Government had reiterated its commitment to change the tax structure  to source 60% from indirect taxes and 40% from direct taxes.

to source 60% from indirect taxes and 40% from direct taxes.

Finance Minister ignoring the promises made by PM

His Finance Minister was supposed to take note of these and many other policy wishes pronounced by the Prime Minister and design a budgetary policy to accomplish them. Instead, what was presented in the budgets for both 2016 and 2017 were policies that would reverse the Government’s expected reforms.

Instead of a promised low tax regime, the businesses continued to be taxed at the same high rates as before. Instead of reducing the reliance on indirect taxes, their share went up to 87% in the first budget which was reduced marginally to 84% in the second budget. Sri Lankans were required to pay taxes on incomes earned both here and abroad.

Contrary to the promise that no taxes would be imposed on past incomes, a special levy was imposed on state banks to transfer funds to the Treasury which amounted to taxing them on past earnings. The only accomplishment was the increase in the tax revenue as a percentage of GDP from 10% in 2014 to 12% in 2016.

Book on tax policy released by IPS should be guide for new Finance Minister

Hence, the new Finance Minister needs guidance as to how he should reform the tax policy. Such guidance is now found in a volume titled ‘Tax Policy in Sri Lanka: Economic Perspectives’ edited by the late Dr. Saman Kelegama and released by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) recently.

It contains nine papers authored by an array of Sri Lanka’s leading economists who have interest in the subject.

Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera

Sri Lanka’s failed attempts at reforming taxes

In fact, Sri Lanka is known as a country which does not have a consistent and logical tax policy. Throughout its history, Sri Lanka had used taxation to attain narrow political objectives and taxes that have been imposed by one administration following the logic of taxation had been abolished by another. Several taxation commissions had been appointed by various governments and reports, prepared after careful deliberations, had also been submitted. But none of the recommendations were implemented though in some cases the reports were released to the public domain.

The latest of such episodes had been the report, released in 2010, of the Presidential Taxation Commission of which Kelegama was a member. In his introduction to the volume, Kelegama admits that the report was limited in coverage. Hence, the purpose of the volume he edited was to fill the gap.

Sri Lanka’s competitive populist politics

An ominous feature of Sri Lanka’s taxation has been the decline in tax revenue as a percentage of GDP as was also noted by the Prime Minister in the Government’s economic policy statement. There have been times in the early 1980s when tax revenue was as high as 18% of GDP. But over the years, the Government’s efficiency of raising tax revenue has fallen drastically to a level of around 10% of GDP by 2014.

Though it increased to 12% in 2016, the current challenge is to sustain that better performance and improve it further in the coming years. Kelegama has diagnosed that the ailment has been due to “unplanned ad hoc tax incentives in the form of exemptions, tax holidays, reliefs, duty waivers, etc.”

These are all unsound political decisions which Sri Lanka could have avoided. Yet, government after government has resorted to the same tactic which Kelegama has called “competitive populist politics” to please voters even when there has not been an adequate resource base to accommodate them.

Ministry of Finance

It in fact vindicates Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s assertion some time back that Sri Lanka was a country which auctions unearned resources. But Sri Lanka has continued to do so and is still doing so.

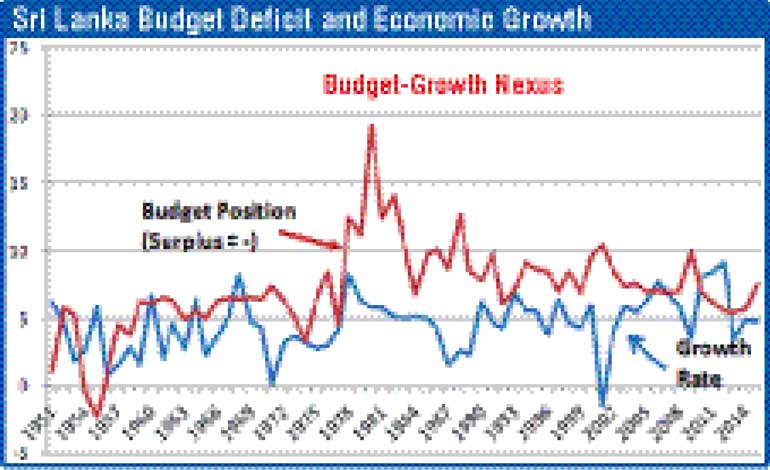

This policy is based on the popular belief that Government expenditure programs are better than private expenditure programs and could therefore deliver miracles for an economy. However, the past data, as shown in the graph, have shown that budget deficits and economic growth rates have moved in the opposite direction.

Present Government is committed to reforming taxes

The present Government, according to the pledge it made to the IMF when securing the Extended Fund Facility in mid-2016, is committed to reforming the tax system to generate adequate revenue while maintaining equity in taxation. In this context, all regressive taxes where the poor have been called upon to pay more taxes in terms of their income relative to the rich have to be abolished.

Kelegama notes in the introduction that the significance of direct taxes in the total tax revenue has declined, while that of indirect taxes has increased. Yet all available research has shown that indirect taxes are highly regressive and should be reformed to ensure equity in taxation without compromising its ability to generate a good income. These are known facts. But the present Government, which is committed to reforming the tax system, appears to be repeating the same mistakes.

The volume is divided into four parts: how macroeconomics has been influenced by taxes, economic perspectives of tax revenue, how taxes affect the production base and how to ensure equity and assess elasticity in taxation.

Taxes creating macroeconomic instability

The macroeconomic side of taxation has been handled by Dushni Weerakoon and Kithmina Hewage in a paper titled ‘Fiscal Policy, Growth and Macrostability’. A salient finding by Weerakoon and Hewage has been that, contrary to the popular belief of policymakers, economic growth has occurred during 2011-2015 due to private consumption and not due to public expenditure programs.

Hence, money spent excessively during this period through public expenditure programs has not been translated into output but has caused inflation, pressure for the exchange rate to depreciate and augmentation of the debt stock. Hence, they have recommended that the budget should be consolidated via an increase in revenue, the curtailment of expenditure, reduction in the deficit and lower addition to the debt stock. These recommendations are in line with the visions of the Vision 2025 document released by the Government recently. What it should do now is pursue a concrete plan to convert words into deeds.

Need for changing the tax structure

Three papers authored by D.D.M. Waidyasekera, Kopapillai Amirthalingam and Mick Moore have dealt with the economics of taxation and the falling tax revenue as a percentage of GDP. With historical data, they have concluded that the current tax level is not the optimal level and it should be increased to gain the maximum benefit for the Government.

It is a policy point at which there is consensus among the Government policymakers, international agencies and researchers. Further, the three writers have drawn the need for changing the tax structure which is heavily oriented towards indirect taxes to a system with more revenue from direct taxes. This is also one of the visions in Vision 2025 and needs to be pursued consistently and steadily.

Tax incentives have not promoted FDIs

The volume contains two papers one by Anushka Wijesinha and Jayani Ratnayake highlighting the impact of taxation on foreign direct investments (FDIs) and the other by Anushka Wijesinha and Raveen Ekanayake on taxes and small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

The first paper has found that though generous tax incentives have been given to FDIs, the actual realisation of same by Sri Lanka has been dismal as revealed by FDI inflows since the early 1980s. This is disappointing since FDIs have been termed the saviour of Sri Lanka today. It is also not surprising since tax incentives are not an integral element in the decision-making parameters of a foreign direct investor. They would value government policy consistency, stability of the government, quality and talented labour and the regulatory structure of the country more than the tax incentives offered.

Wijesinha and Ratnayake have argued that the best structure for a country is a low tax regime and both local and foreign investors should be given the same tax treatment. But they have warned that the elimination of tax incentives should be done cautiously over a period of time.

SMEs are to be incentivised through structural support and not through tax exemptions

Wijesinha and Ekanayake have produced their paper on SMEs and taxation based on a field survey conducted. SMEs are important for any economy since they constitute the largest segment of enterprises, provide employment to the majority of workers and contribute a sizeable volume to the country’s national output. Though there is a general belief that tax incentives would cause to promote SMEs, Wijesinha and Ekanayake, through their survey, have found that about 93% of SMEs in Sri Lanka do not pay taxes. Hence, tax incentives are immaterial to them. Since the future role of SMEs is to be a part of the larger global supply chain, it is better to incentivise the large manufacturers who outsource their products from them.

Tax reforms should not compromise social security concerns

Nisha Arunatilake and Priyanka Jayawardena, in a paper titled ‘Accounting for Social Effects of Tax Reforms’, have argued that any tax reform to be introduced should take into account how it would affect the vulnerable groups and there should be a social security system to alleviate their misery.

They have used a model to estimate the incidence of taxation across households, impact on tax revenue and welfare of people. In the empirical findings, they have found mixed results, implying that all tax reforms should be carefully thought out.

Statistical validation of low tax yield

Yuthika Indraratna has estimated the tax elasticity in Sri Lanka using the data from 1960 to 1994 in her paper titled ‘Measurement of Tax Elasticity: A Times Series Approach’. She has found that the tax elasticity during this period has been less than 1, meaning that tax income of the Government has not increased at the same rate as the growth in the income.

The main culprits for the poor results, according to Indraratna, have been tax exemptions, duty waivers, tax incentives, low compliance and the emergence of non-tax paying vibrant sectors in the economy. All these are shortcomings of policymakers who have failed to follow a consistent and logical tax policy. However, the statistics used by Indraratna are somewhat dated and it will be useful if she or some other researcher tests her model against the data from 1994 to ascertain whether it is a continuous phenomenon in the country’s tax system.

A book worth being read by all policymakers

Overall, the present volume edited by Kelegama is a good attempt and it certainly adds knowledge and helps policymaking. Thus, Kelegama should be posthumously congratulated for bringing out this volume. However, these policy prescriptions will remain mere policy prescriptions on paper if they are not used in public policy. Sri Lanka’s public policymakers are known for ages for working in isolation from the rest of the free thinkers in society. Hence, it is useful if policymakers, especially those at the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Economic Affairs, devote some time to study these policy recommendations and adopt them for the betterment of the country’s economy.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])