Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Tuesday, 17 December 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka became famous/notorious for shutting down Facebook in 2018 and then on a larger scale in 2019. But our neighbour India is the world’s champion in shutting down the internet, and sometimes and in some places entire mobile networks. Nepal in the time of the former King Gyanendra shut down all forms of electronic communication.

It is one thing to write about shutdowns; but quite something else to actually experience an Indian shutdown. I experienced it in Assam and Meghalaya in the North East of India (on the other side of Bangladesh) the last few days.

Before leaving Kolkata, I tweeted: “I am leaving W Bengal for Assam where internet will be shut down from midnight today. Hopefully I will get to Meghalaya before that and my location will not affected.”

Cyberspace and physical space

When the Air India flight landed an hour late at the Guwahati airport the tension was palpable. Some said the networks were already down. But my roaming phone was working. I was thinking the fuss is all about cyberspace; physical space seemed fine. Lots of vehicles were in the parking lots and on the roads. A colleague and I set off on the two plus hours journey to Shillong.

Physical space was being shut down before cyberspace. The main highway was blocked by gangs of men burning tyres. My friend was searching for alternative routes on his smartphone. Failing that he looked for a place to stay overnight. Google maps to the rescue. We got off the highway and found a hotel which had rooms.

Absence of internet

Another group that landed after us also got stuck. By the time they learned the highway was closed, the internet was out. No way of finding shelter. No maps. But voice calls were possible. They made their way to our hotel guided by our driver. Where would we all be had we not found food and shelter before the switch was thrown?

In the early morning we managed to get to Shillong. Even rioters have to sleep.

The shutdowns continued for the next few days, but not uniformly and completely. My roaming phone would catch a 4G network sometimes and I would have a few minutes of connectivity. The fixed  connection in my guest house worked, but slowly and erratically. I was able to send and receive SMS, but my Indian colleagues could only receive texts, some times. Smartphones had been converted to dumb phones with cameras and flashlights.

connection in my guest house worked, but slowly and erratically. I was able to send and receive SMS, but my Indian colleagues could only receive texts, some times. Smartphones had been converted to dumb phones with cameras and flashlights.

Internet is a precondition

Some attendees were calling their offices and families, trying to reschedule flights. But each option had a missing piece. If a ticket was bought by the office located where the internet was working, how could that be sent to the traveller stuck in Shillong, who would need a printout to get into the airport? Other options required one-time passwords (OTPs) sent to registered numbers. With SMS blocked, that was not a possibility. And even if tickets could be had, where to find taxis willing to brave the bandh?

Only a few locations which had fixed connections via BSNL allowed access to Internet. The shutdown was being enforced on the mobile operators only. I would sometimes get connected because of priority routing for international roamers.

Skirting boulders on roads and driving past remnants of burnt tyres, we got to within walking distance of the Guwahati airport on Saturday morning. Physical space was open; traffic was moving; some shops were open. But still no Internet; still no SMS. Just voice calls. Credit cards payments could not be made in most places. The much-vaunted mobile payments promoted by the government were dysfunctional. Some were short of cash because ATMs were not working.

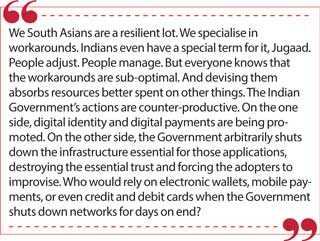

Shooting ourselves in the foot, but limiting damage

We South Asians are a resilient lot. We specialise in workarounds. Indians even have a special term for it, Jugaad. People adjust. People manage. But everyone knows that the workarounds are sub-optimal. And devising them absorbs resources better spent on other things.

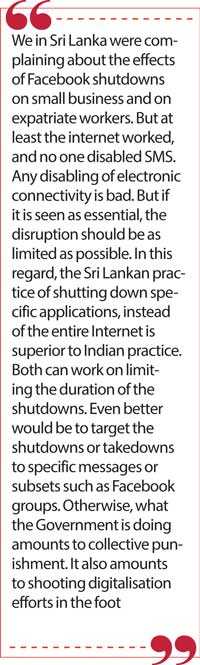

The Indian Government’s actions are counter-productive. On the one side, digital identity and digital payments are being promoted. On the other side, the Government arbitrarily shuts down the infrastructure essential for those applications, destroying the essential trust and forcing the adopters to improvise. Who would rely on electronic wallets, mobile payments, or even credit and debit cards when the Government shuts down networks for days on end? We in Sri Lanka were complaining about the effects of Facebook shutdowns on small business and on expatriate workers. But at least the internet worked, and no one disabled SMS. Any disabling of electronic connectivity is bad. But if it is seen as essential, the disruption should be as limited as possible. In this regard, the Sri Lankan practice of shutting down specific applications, instead of the entire Internet is superior to Indian practice. Both can work on limiting the duration of the shutdowns. Even better would be to target the shutdowns or takedowns to specific messages or subsets such as Facebook groups. Otherwise, what the Government is doing amounts to collective punishment. It also amounts to shooting digitalisation efforts in the foot.

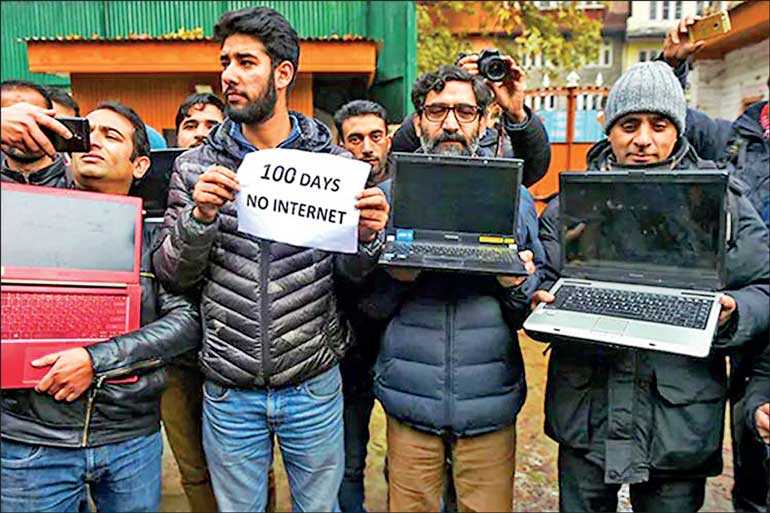

This is actually what has been going on in Kashmir now for over four months. The difficulties I experienced for a few days are nothing compared to the continuing difficulties faced by the people still deprived of basic connectivity in Assam and Meghalaya. And those are minuscule compared to what is being experienced in Kashmir and Iran right now.