Monday Mar 09, 2026

Monday Mar 09, 2026

Wednesday, 13 May 2020 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

SL apparel industry at a glance

Sri Lanka is one of the best and most ethical garment manufacturing destinations in the world. We have proven that international labour standards and high-quality management processes are being followed as evidenced in the slogan ‘Garments without Guilt,’ which demonstrate how ethical practices are at the root of the industry's success.

Why is the apparel industry important to Sri Lanka?

Apparel is the single largest industry generating a revenue of $ 5.5 billion which contributes to 44% of Sri Lanka’s merchandise exports with over a 500,000 workforce (15% to the total workforce), whilst the second largest contribution comes from the tea industry contributing to 12% of total merchandise exports. Moreover, 85% of the workforce comprises of women and any negative impact to their jobs will have spillover effects on the country’s sociocultural factors.

SL reports a negative trade balance of $ 8 billion (2019) and as a result the rupee is being depreciating throughout. SL is having subnational loan amount of $ 73 billion (87% of GDP) to payoff. Therefore, we need to protect and develop this ‘cash cow’ to overcome the challenges we are currently facing. It is evident, that we cannot only depend on the service sector anymore due to its prevailing sensitivity.

Retail market outlook (post-COVID-19)

The overall apparel business is becoming increasingly competitive, and this was seen even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. High labour cost, trade barriers and aggressive competition from low cost destinations in the market are just a few reasons. However, the world has started to move towards destinations offering agility and scale. So, whoever can offer “faster, cheaper and better” solutions will win the battle.

In the wake of COVID-19 pandemic, people have already lost or are in the process of losing their jobs and we cannot expect the same buying behaviour from our consumers. Basic needs have now become the priority with people spending more on food and essential products, while the least priory would be given to fashion. The market is expected to behave in this manner at least for the next six months.

Industry cost structure

Industry cost structure

The apparel industry generates money from its capacity. However, 70% of the total cost comes from raw materials (variable cost) and only a ‘contribution margin’ of 30% is available to cover all other expenses and secure profit. The average salary and wages costs around 18% to the sale value, which is around $ 900 m per month for the industry (based on $ 5 b export value), however the Sri Lankan Government’s bailout package for the ‘entire country’ is only $ 270 m [Rs. 50 b], which is not sufficient to rescue any industry.

The question, therefore, is how can manufacturers afford this cost? The only option is Government intervention to grant term loans schemes with an interest rate of 3% to 4% which can be paid up to two to three years with a grace period in the first six months.

Best practices from regional players

Cost of sale is around 70% in the industry where all purchases were done under LC at sight or 30 days differed payment upon receiving the goods. This means manufactures have to block this money to open LCs, while customers take the benefit of paying after an average of 60 days to manufacturers (now extended up to 120 days due to COVID-19).

In addition, with the average of 30 days manufacturing lead-time, an average cashflow of 180 days (six months) is created. Therefore, manufacturers will have to fund this by default, which is one of the main drawbacks of having a few key players in Sri Lanka. In this situation ‘cash’ is key and let’s see how other regions manage this challenge.

How do other regions manage cash flow with government support?

In Bangladesh, exporters are entitled to obtain a facility called ‘Export Development Fund (EDF),’ which intends to provide financing facilities for the procurement of raw materials. How does this work?

Each manufacturing company is eligible for $ 25 m worth of funds, where exporters can procure the direct raw material (fabric and accessories) without holding their reserves. This fund will act as collateral for the pending export payments. This enables the exporters to have a maximum of 180 days as credit period for settling the EDF loan to their suppliers, with an interest fee of LIBOR+2.5%.

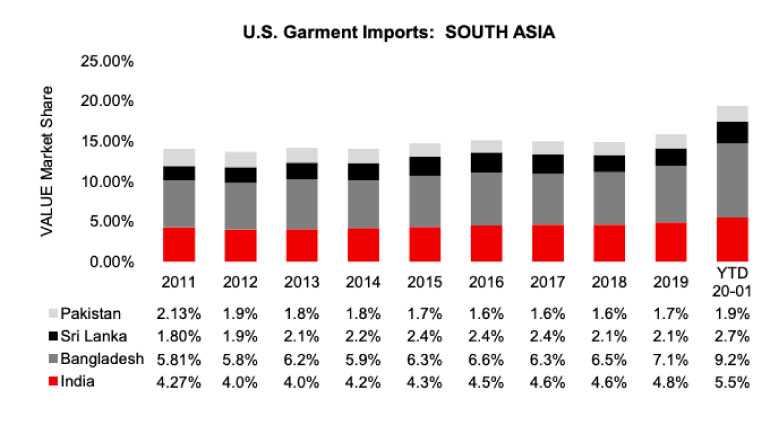

It is also important to note, that due to contraction in demand after COVID-19, the repayment period has been extended up to 360 days. As a result, Bangladesh has a steady growth in apparel exports in comparison to Sri Lanka.

Regional sourcing strategy

While Sri Lanka generates revenue of $ 5.5 b, the net contribution is around 55% [$ 3 b] Sri Lanka relies extensively on its raw materials from other regions, where 40% of fabric and accessories are imported from China, even though they are known as an expensive hub with wage costs being twice as much as Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile, other regions have successfully built end to end verticality to increase the value creation within themselves. It is important for the Government to revisit its import strategies and control vital categories; one being cotton fabric, as Sri Lanka has the know-how in manufacturing them. Thus, propagating and providing financial assistance to encourage investments on vertical supply chain is key.

Target on non-traditional markets

While other manufacturing destinations are targeting the US and EU markets it is important that we also explore other new markets.

The Ministry of Commerce in Bangladesh has established a mechanism to provide additional cash incentives for exporters of garments to the non-traditional markets. Apparel exporters are enjoying the benefit of general cash subsidy at a rate of 4% to FOB.

Cost leadership model

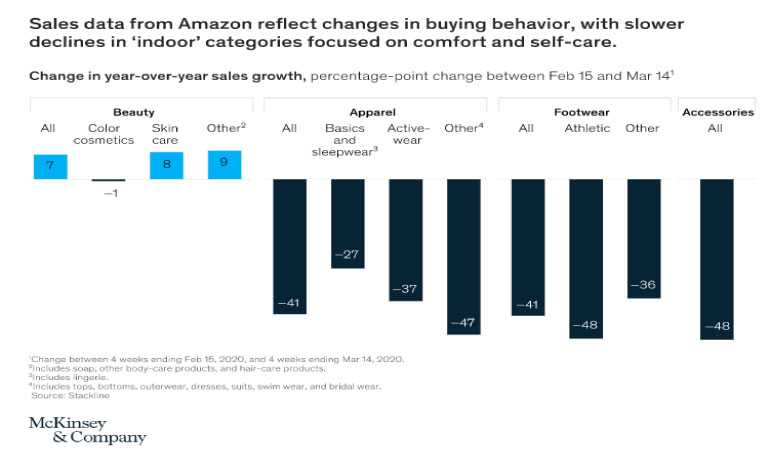

Post-COVID-19 customers’ purchasing behaviour has resulted in a 40% reduction of demand, in the apparel sales in the US and EU. As a result, basic styles started to have the minimum impact while high-end and fashionable products have taken a downward curve.

The buying pattern of customers has started to shift towards essential clothes from supermarkets such as M&S, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, LIDL, ASDA and others. Thus, it is evident that customers have become more conscious about the choices they make, by opting for a one-stop-shop as opposed to going for specialty retailers. A key highlight of this fact is, retail prices are 30 to 40% cheaper in supermarket models than a normal department or specialty retail store.

As a consequence of this, Sri Lanka will not be able to charge the same average price per garment or expect the same style range from its customers as it used to. In fact, low-cost destinations have a greater potential to recover from this impact versus Sri Lanka.

The right approach to this would be flatter organisational structures and a cost leadership model. Manufacturers should give more focus on monitoring and driving each cost element, while higher management should prepare themselves for this change, acting as the change agents leading and inspiring change.

Scale is important to manage this crisis

Cost-leadership comes with scale and consolidation. Therefore, SMEs will need to explore options on how they can partner or merge with bigger players in the market. The time is undeniably right to go for ‘industry consolidation’ and it is vital and relevant, more than ever before.

The global apparel FOB business is around $ 480 b, therefore fighting among and over local competition is not worthwhile as we as a nation only account for $ 5.5 b of apparel exports (which is less than 2% of market share), whereas there’s a significant share which can be seized from other regions. In this backdrop, a win-win mindset is required as opposed to traditional leadership models. Only ‘faster, cheaper and better’ will win this game.

(Sachith Balage, an expert in the apparel sector, is presently based out of Dhaka in Bangladesh. He can be reached on [email protected].)