Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 23 June 2020 00:52 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

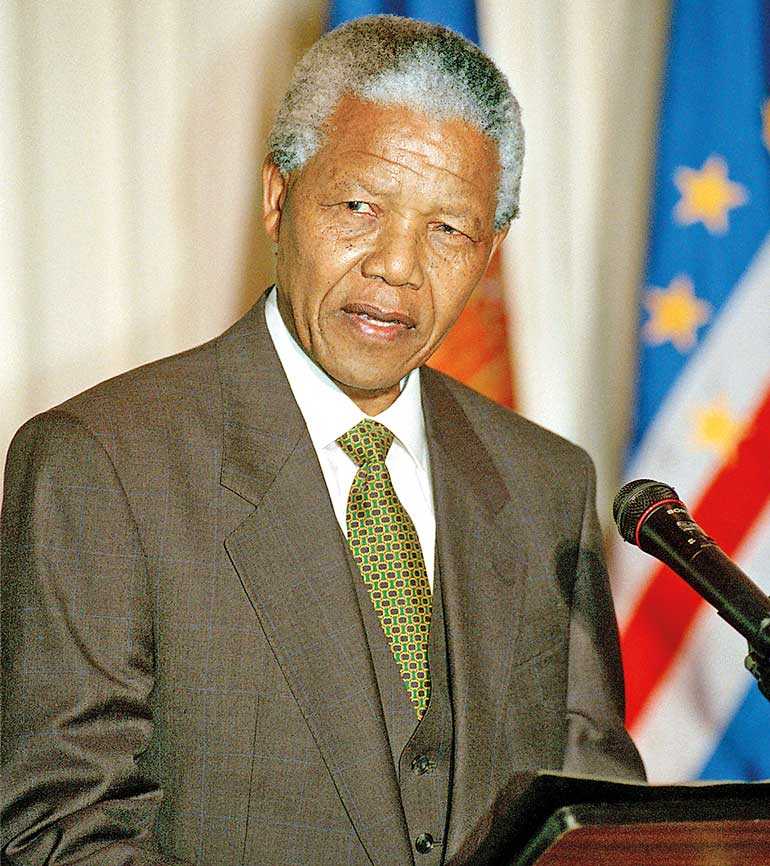

COVID-19 has compelled us to ask questions about leaders and leadership. What kind of leaders do we have? Do we have Mandelas? Do we have people who could one day rise above circumstances, lead everyone and not just those who voted for them, and become leaders like Mandela? If we don’t have such leaders, we need to answer another set of questions.

“It is better to lead from behind and to put others in front, especially when you celebrate victory when nice things occur. You can take the front line when there is danger. Then people will appreciate your leadership” — Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela was a rare leader. It would be hard to imagine two individuals like Mandela inhabiting the earth at the same time. In fact, very few countries can boast of several leaders like him in their respective histories. This rarity is probably why he is celebrated not just in South Africa but the world over. Nelson Mandela is the leader every country wants to have but doesn’t. The Nelson Mandela yearning gains greater currency when the world, a nation or even a political party faces a serious leadership crisis.

It can be said with certainty today that COVID-19 not only took the world by surprise but threw it into confusion and even chaos. Unexpected turns of events can do that, but if humankind has overcome adversity that arrives unexpectedly and in magnitudes of this nature, more often than not it is because of resolute leadership.

COVID-19 exposed a lot of weaknesses and errors in multiple spheres of humanity but none so stark as our lack of good leadership. There was no global response to speak of. The World Health Organization, for all its good intentions, was caught wrong-footed. The leaders of powerful nations quickly opted to play a blame-game, pointing fingers at each other. Naturally, while there was no concerted global effort to combat the pandemic, individual countries, including the economically powerful, floundered.

Ideally, leaders would coordinate efforts, using power vested in their respective offices to implement a concerted, coordinated and efficient strategy that is principally informed by the advice of those who are well versed on the subject of pandemics and how to combat them. This did not happen.

Individual political survival seemed to be what mattered most, not the wellbeing of the respective populations. The expertise of scientists and healthcare professionals played second fiddle to political expedience. Leaders continued to depend more on political advisors than relevant professionals.

The last few months showed us that there were a handful of leaders with vision, but even they lacked action plans, political will and drive. There were leaders who were action-oriented but without vision. Then there were leaders who had neither vision nor action plan. Lack of integrity compromised credibility and the power to mobilise populations in the necessarily collective effort to combat the threat. We saw leaders indulging in speculation. We heard grand proclamations of imminent success absolutely at odds with the horrific reality of the spread, the numbers infected and victims. What we didn’t see was humility to acknowledge limitations, courage to be honest with the citizens and a sense of purpose that could convey the message that regardless of how formidable the challenge, no pains would be spared to overcome it.

Clarity has always been a key strength of successful leaders. In times of confusion seriously compounding all the terrors that attend pandemics, it is this quality that must come to the fore. Unfortunately, we either see leaders using sunshine stories to gloss over their ignorance or else treating the citizens as passive consumers of their policy decisions. The latter is the Godfather approach where the thinking can be captured as follows: ‘I am doing this for your good, trust me; I know what I am doing, trust me.’ Trust, however, is not something that can be won simply through legislation or executive decree.

If history has demonstrated anything about effective leadership, it is that those who succeed tend to be honest and clear about what they want to accomplish and for whose benefit. Such leaders gained loyalty and trust by being truthful and frank, regardless of possible negative political fallout. Even if they could not envisage a phenomenon such as COVID-19, they had all the qualities required to meet such threats — courage, determination, humility, ability to inspire people and mobilise resources, and most importantly the integrity that gelled it all together. They were clear about what is possible and what is not. They were not ashamed to admit errors, welcome blame and give credit to their people. They were quick to correct mistakes. They did not hide behind numbers and half-truths. They did not sweep uncomfortable truths under the carpet or disguise them in happy colours.

Such attributes cannot be gathered overnight, of course. Integrity, for example, is a quality that has to be nurtured over a long period of time. Indeed, it takes time for a citizenry to recognise integrity because words and deeds have to be seen as being consistent with intention in numerous situations and not one-off decisions or actions. Integrity is also measured in terms of the ability to make sacrifices and denial to oneself of any and all special privileges typically available to political leaders. Example counts as much or more than precept. Empathy is measured in terms of concrete acts and not words.

Incorruptibility is another rare attribute and one which we hardly see in political leaders today. Corruption, turning a blind eye to corruption, and placing public trust in those with checkered histories, all go a long way towards compromising credibility. No leader who is thus tainted can hope to mobilise a people to fight a pandemic. People will not trust such a leader. They will not believe what is said and will be more hesitant to follow.

If a leader is not fair or if a leader fails to treat everyone equally irrespective of differences such as religion, ethnicity, sexual preference, gender, class, caste and ideological choices, there will be serious doubts regarding his or her integrity. Once integrity is questioned, it is hard to lead a people. It is only possible to serve a few; some and not all.

A successful leader on the other hand, will recognise the higher worth of a meritocracy, have an unerring eye to identify talent and possess the tone and words that will compel the talented to play the particular role to the best of their ability. Such a leader will see beyond self, party and election, identifying future leaders and grooming them for succession. Endowed with the ability to see and think ahead, they will know who is likely to be better equipped to lead the nation into a future made of different challenges in an ever-changing social, economic and technological milieu.

COVID-19 has compelled us to ask questions about leaders and leadership. What kind of leaders do we have? Do we have Mandelas? Do we have people who could one day rise above circumstances, lead everyone and not just those who voted for them, and become leaders like Mandela? If we don’t have such leaders, we need to answer another set of questions.

How do we identify a dearth of leadership? Real leaders are people who see things that others do not. Yet far too often, the people who claim to lead us seem oblivious to truths that are glaringly obvious to those in their charge. Real leaders hold strong beliefs, whether in ideas or principles, and inspire others to follow. In our lives, those who lead seem to decide on their words only after calculating the popularity of their ideas.

In times of crisis, real leaders have the courage to take a stand, to take risks and put themselves in harm’s way, politically or physically, and stand up for what they believe. They must be able to understand the present, envision a better future, and successfully navigate from one to the other. They need to plan for the long-term and be able to adapt to unexpected challenges in the short-term.

Any good leader knows that no man or woman is an island unto themselves. The secret to their success is often the ways in which they harness the talents of others and move communities forward as one.

Albert Einstein made it a point to invite and respond to correspondence from scientists across the world, exposing him to all the finest ideas in the world. He once even translated into German a paper by a young Indian scientist he had never met to get it published in a European journal. Abraham Lincoln famously had his “team of rivals” and harnessed their diversity of opinions and experience to victory in the American civil war. 15th Century Chinese explorer Admiral Zhang handpicked a team of seasoned sailors and soldiers who built and managed trade routes from across Asia to the horn of Africa.

The old adage of military camaraderie, “leave no one behind”, is as fundamental for successful leaders in a boardroom or Parliament as it is to generals fighting in a war. Too often, leaders throw their people to the wolves, leaving them to fend for themselves in times of need, rather than come to their aid and stand up for their people. A leader must be able to surround themselves with the finest talent available and assemble a capable and dedicated team to see their vision through to implementation.

It is difficult to attract such talented people to serve in any capacity if they feel that they are expendable to those in charge. Indeed, in some political parties and organisations, capable deputies are sidelined and isolated, while the weakest of the pack were elevated in order to secure the party leader’s position by dislodging and isolating anyone who may have been “next in line”.

But this cancer is one that seems to be prevalent across our society, preventing future leaders from rising. Is it that we have a system that rebels against the emergence of great leaders? Do we not have a system that inhibits the nurturing of leadership qualities? Is it that those who possess such qualities are systematically prevented from becoming leaders or are discouraged from entering politics or are essentially disqualified because of identity, socio-economic background, ideology, religion or race?

Finally, we need to ask ourselves what is perhaps the most crucial question of them all: do we, as individuals and a society wait for a hero like Nelson Mandela or do we rehearse the heroic ourselves — acquiring, practicing and perfecting the requisite qualities and deploying them whenever and wherever possible, slowly but surely expanding our spheres of engagement?

This is an issue that will outlast COVID-19, which will not be the last challenge we face as a community of nations. The pandemic will leave economic carnage in its wake, and with the climate rapidly deteriorating and major powers flexing their muscles, we can expect more crises on the horizon. With this certainty in mind, we have an obligation as a species to either improve our existing leaders or to nurture new ones from amongst our ranks. People are not “born to lead”. Long before Nelson Mandela became a household name, he worked as a cattle-boy tending cows with his illiterate parents in a rural South African village.

Our leaders can come from any walk of life. It is up to us to see past our own stigmas about so-called acceptable genders, classes, ethnicities, ages, religions and castes, and to recognise and promote future leaders who have the ideas, dedication, teambuilding skills and competence to navigate the trying times ahead.