Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Wednesday, 7 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka has made great strides in the arena of tobacco control with the imposition of graphic health warnings on cigarette packs, public place smoking ban, purchase age restrictions and a preventive pricing regime that renders stick prices amongst the highest in the world.

Sri Lanka has made great strides in the arena of tobacco control with the imposition of graphic health warnings on cigarette packs, public place smoking ban, purchase age restrictions and a preventive pricing regime that renders stick prices amongst the highest in the world.

In consequence, one would anticipate that these measures made a significant impact on Sri Lankan smoker incidence, but in reality, they haven’t and smoking rates remain relatively constant. This conclusion is derived from figures gathered from the market, during discussions with traders and consumers islandwide.

The former Health Minister who is now our President, and the current Health Minister both espoused a country free from tobacco when they put in place the above measures. But the failure to impact smoking rates are the result of inaction on two critical fronts.

On one hand we are posed with the problem of contraband. Smuggled foreign brands are available in most urban areas and are attractive to local smokers due to price and perceived prestige, and retail at an average Rs. 40 in contrast to legal products which are priced Rs. 10 higher.

Official estimates point to over 100 million sticks entering the Sri Lankan market illegally throughout the year. Media reports point to a large number of detections of contraband by authorities at points of entry, and the government is now mulling issuing new licenses to stem illegal imports. Licensing new imports will do little to control smoking prevalence.

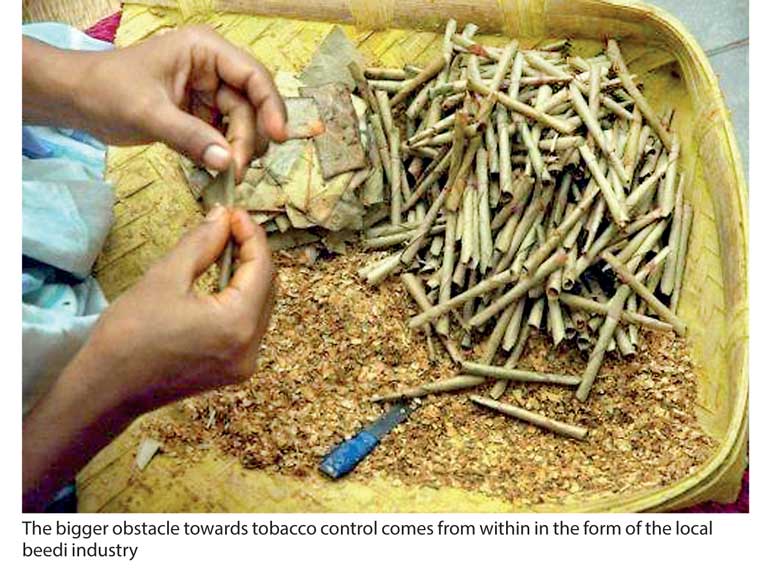

However, the bigger obstacle towards tobacco control comes from within in the form of the local beedi industry. It is grossly incorrect to still term this trade a cottage industry, as it is in real a multi-billion-rupee industry employing thousands of Sri Lankans islandwide with no form of regulation of taxation.

In the Hakmana area, we had the opportunity to meet with a beedi manufacturer, working as a sub-contractor, who in turn employed 32 families rolling out over 1,000 sticks day. He revealed there were four other sub-contractors such as himself working for the trader in the area. Some simple math would then tell us that on a 22-day work month, these five sub-contractors and their workers churn out 4.2 million sticks annually – in the Hakmana area alone!

This presents a mere tip of the iceberg. There are over 500 licenses issued for the manufacturing of beedi in Sri Lanka. The age-old practice is to measure beedi production via the importation of Tendu leaves from India, and as the Central Bank itself acknowledges this process of measurement is grossly misrepresentative and outdated.

We encountered similar operations in the Anuradhapura, Kandy, Matale, Kegalle, Badulla, Puttalam and Colombo Districts with every household striving to roll a 1,000 sticks a day for the traders. In our estimate, on average every province contains over 650 families engaged in beedi manufacturing – rolling and labelling – and upon extrapolating the above numbers we arrive at an island wide annual figure of over four billion sticks.

These four billion sticks are priced at Rs. 5 each and present no tax revenue to the Government. Retailers say they sell on average five bundles of beedi a day. In addition, they remarked that beedi sales have grown over the past one year relative to cigarettes, following the sharp increase in price of the legitimate products.

With four billion sticks in the market, the imposition of a tax of just Rs. 5 on a beedi will yield Rs. 20 billion in much needed revenue for the Government. The tendu leaf tax is irrelevant and it is grossly misrepresentative. The Government needs to add tooth to its effort on tobacco control and device a mechanism to tax beedi at the point of production or sale, lest it wants to suffer the ignominy of having achieved nothing for all its clamour. But whether the Government will find the real motivation and will to do so in the light of concerns over antagonising the voter base and members with vested interests in its own fold remain to be seen.

There is a lot to be gained by widening the tax net and regulatory control over the ‘cottage industry’. Besides the revenue aspects, it will enhance understanding and control over health and social investments and strengthen law and order.

With over 16,000 families engaged in manufacturing beedi islandwide, there are further environmental and social issues that requires attention, which we will discuss in time to come. But if the Government is really committed to controlling tobacco consumption in the island, then it must extend its controls to the beedi trade.

There is little point in brandishing regulatory achievements on any stage if an informal sector is allowed to prosper as a cheaper but inferior alternative; effecting the same ills and more the Government claims to have controlled. Once again, it is a question of political will and the courage to do what is right; rare attributes within Sri Lanka’s corridors of power.

(The writer is a Researcher engaged in social and economic impact analysis.)