Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 27 October 2021 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

‘JR’s Kandy March,’ as it came to be known, played a very negative role in souring ethnic relations in the island

Many believe that if the B-C Pact had been allowed to work, the history of the island’s ethnic conflict may have been different

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike

S.J.V. Chelvanayagam

J.R. Jayewardene

S.D. Bandaranayake

Philip Gunawardena

Stanley de Zoysa

C.P. de Silva

Anandatissa de Alwis

In my article ‘SWRD’s flirtation with federalism’ published in these columns on 29 September, I had referred to the pact signed by the then Prime Minister Bandaranaike and Tamil political leader Chelvanayagam in 1957. What I wrote then was as follows:

In my article ‘SWRD’s flirtation with federalism’ published in these columns on 29 September, I had referred to the pact signed by the then Prime Minister Bandaranaike and Tamil political leader Chelvanayagam in 1957. What I wrote then was as follows:

“The agreement signed by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and S.J.V. Chelvanayagam in 1957 was a significant event in the political history of post-independence Sri Lanka. The Prime Minister of the day and the Leader of the biggest Tamil political party had come to an understanding which if implemented may have helped contain the ethnic conflict at its nascent stages.”

“The agreement known generally as the ‘Banda-Chelva Pact’ was never allowed to work because of political opposition in the south. The opposition came from hardliners among the Sinhala Buddhist clergy and laity as well as hawkish elements among both the Government and Opposition.”

“The United National Party (UNP) was vehemently opposed to the B-C Pact, calling it a sell-out of the Sinhalese. The UNP had only eight seats in Parliament being buried in the landslide victory of SWRD in 1956. With Sir John Kotelawela reduced to a mere figurehead and Dudley Senanayake becoming inactive it was Junius Richard Jayewardene’s task to revive the UNP’s flagging fortunes. Just as SWRD rode to power by playing the communal card, JR too resorted to communalist politics to discredit the new regime. Jayewardene seized on the B-C Pact as a vulnerable target and began whipping up communal frenzy against it.”

I have been receiving a lot of feedback about this article in the past weeks. Interestingly enough much of it has been about J.R. Jayewardene’s role in attacking the Banda-Chelva Pact. Several readers opined that the UNP opposition to the BC Pact spearheaded by J.R. Jayewardene was instrumental in the agreement being negated. Many were critical of JR saying that if the B-C Pact had been allowed to work, the history of the island’s ethnic conflict may have been different.

There were also specific requests and suggestions that I write in detail about the protest march to Kandy, planned and led by JR in October 1957. It is against his backdrop therefore that this column focuses on the notorious protest march led by JR against the B-C Pact.

The notorious protest march

The historic agreement between Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and Ilankai Thamil Arasuk Katchi (ITAK) Founder S.J.V. Chelvanayagam known as the Banda-Chelva Pact and/or B-C Pact was signed on 26 July 1957. A key provision of that agreement was the proposed setting up of regional councils as a unit of devolution.

Consequently the UNP languishing in opposition with eight seats began targeting the pact on communal lines and accusing Bandaranaike of conspiring with Chelvanayagam to divide the country. The UNP began toying with the idea of organising a massive road march in protest against the alleged betrayal of the country through the B-C Pact.

The UNP first thought of trekking on foot from Colombo to Anuradhapura and swearing before the sacred Bo tree that they would safeguard the country by opposing the B-C Pact. That plan was shelved by J.R. Jayewardene because the 119 mile journey was too long and also because the greater part of the route was through sparsely populated areas and jungles.

It was decided then to march to Kandy and take the oath at Dalada Maligawa. JR wanted to make a grand spectacle of it and the densely-populated areas along the Colombo-Kandy road as well as the shorter distance of 72 miles was ideal. A public meeting was scheduled at the ‘Paddiruppuwa’ at the end of the march. The Mahanayakes of Asgiriya and Malwatte chapters were persuaded to extend an open letter of invitation requesting people to assemble in Kandy on 8 October and take a vow before the Sacred Tooth Relic that they would prevent division of the country through the agreement between Bandaranaike and Chelvanayagam.

The day, 8 October 1957, was a full moon Poya Day. JR’s plan was to start a six-day march on 3 October and reach Kandy well in time for the mass rally on the 8th. The marchers describing themselves as pilgrims wanted to cover 12 miles each day. The S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike-led MEP Government was perturbed by the potential political mileage the UNP could derive through a successful march. The national press criticised the plan as one that could cause communal unrest and violence. Various pressures were exerted on JR to call it off but he stood firmly by his decision.

One man who anticipated Government instigated violence was former Premier Sir John Kotelawela. Sir John was yet the nominal head of the UNP. He warned the party that “Banda” would not allow the march. Being a pugnacious personality, Sir John advised party members to arm themselves and resist violence with counter violence. This of course was not followed.

Dudley Senanayake who resigned as Premier in 1953 and faded away from active politics had made a re-entry in 1957. He too joined the march and was in the forefront when it began. However Dudley had no role in planning or organising the protest. The ‘Kandy March’ was essentially JR’s brainchild.

Violence unleashed

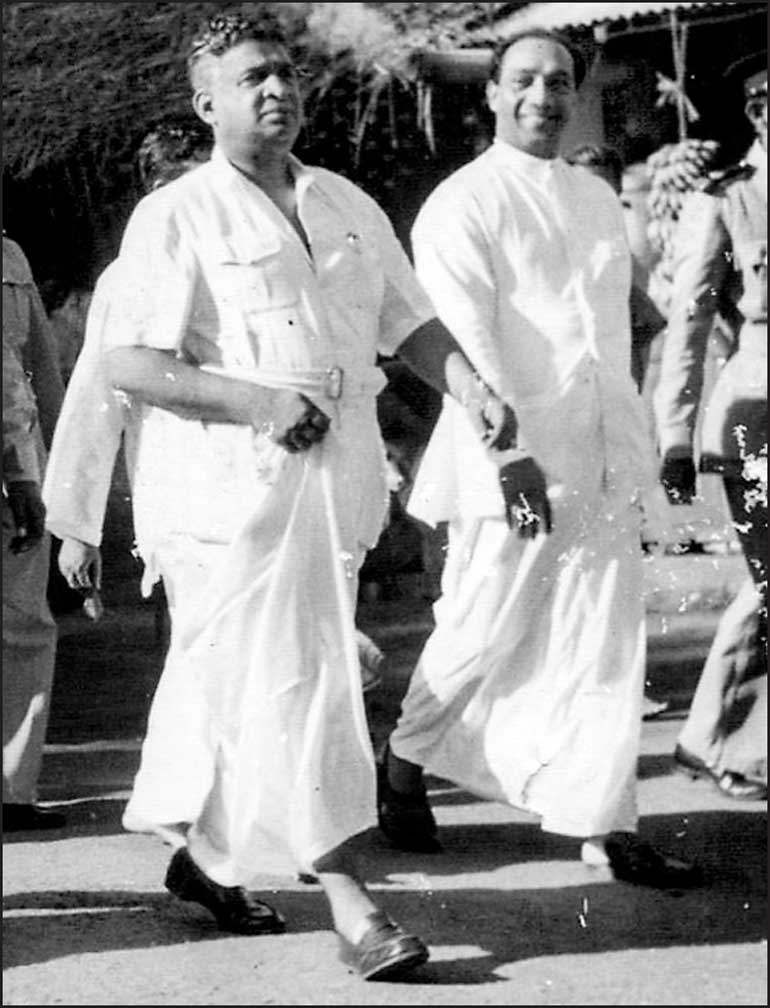

Thousands of UNP stalwarts and supporters including J.R. Jayewardene, Dudley Senanayake, MD Banda, Anandatissa de Alwis, Dr. M.V.P. Peiris and Ranasinghe Premadasa began the march from Colombo on 3 October. Violence was unleashed in the form of stones, slippers and bricks being thrown and marchers being beaten. Cabinet Ministers like Philip Gunawardena, William Silva, Stanley de Zoysa and C.P. de Silva were suspected of organising gangs to attack the marchers. It is believed that former Colombo Central MP MS Themis also sent his thugs.

The stoning was intense in areas like Grandpass and Peliyagoda. The Police did nothing as they had been instructed not to intervene. Mobs of Government supporters gathered along the route and began hooting and jeering. Several traffic jams were caused by the march. Many turned back due to the violence. Some of the UNP “toughies” also retaliated. The marchers walked 12 miles and reached Kadawatha to rest for the night. Once again Government-backed mobs began to stone the houses in which UNP marchers were staying in Kadawatha. Again the Police did nothing.

JR’s younger brother and eminent lawyer HW Jayewardene queried from Deputy Inspector General of Police CC “Jungle” Dissanayake whether the Police would not stop the attacks, to which the DIG replied that his orders were not to interfere. HW then threatened “Jungle” with a lawsuit for dereliction of duty in the face of a threat to peace. Thereafter the DIG exceeded his orders and extended protection to all the houses.

‘Missile’ unleashed

JR hoped to end the second leg of the trek at a Buddhist Vihare in the Attanagalle electorate. Attanagalle then was the pocket borough of the Bandaranaikes. Allowing JR to march in and tarry for the night was seen as a political challenge and personal affront. Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike summoned Gampaha MP and kinsman S.D. Bandaranayake and assigned the task of stopping the march before it reached Attanagalle. SWRD had at one time described the maverick S.D. Bandaranayake as an “unguided missile”. The unguided missile was now given a definite “target and coordinates”.

S.D. Bandaranayake planned a strike that was intended to shock and awe. Anticipating that the marchers would reach Imbulgoda along the Colombo-Kandy road in the morning “El commandante” SD mapped out his strategy. There was a particular spot on the road that was very conducive for a “guerrilla” attack. The road was narrower and had embankments or small hillocks on either side around a short bend. It was an ideal place to launch an attack as it was possible for the assailants to have a field day pelting stones down on the marchers.

The UNP recommenced its march at first light on 4 October. Most of JR’s demoralised followers had deserted him overnight. Instead of the thousands of people marching on the first day there were only about 125-150 people ready to follow the leader. The streets of Kadawatha too were generally deserted and there were no jeering mobs.

Three miles of marching saw the UNP reach Imbulgoda at 7:20 a.m. At one point the marchers saw two vehicles parked in the middle of the road. A man was lying on the road between both vehicles. The horizontal obstacle was none other than Gampaha MP S.D. Bandaranayake. About 150 people were sitting on the road behind the vehicles. More than 500 persons were standing on either side of the road with objects to be thrown at the marchers.

One of the vehicles on the road was the Volkswagen bearing the number 1 Sri 1901 which belonged to S.D. Bandaranayake. The people of Gampaha had presented it to him in September. The other vehicle was owned by SD’s political associate Dr. M.C. Chandrasena who was standing behind it.

When the UNP procession reached “ground zero” SD’s storm troopers began throwing kurumbas, kombas and then stones at the marching persons. The protest march participants scattered and some sought refuge in nearby homes and boutiques.

Calling off the march

Former Police Assistant Superintendent D.S. Thambaiyah was in charge of security in that area. Even as the stone throwing began, he intervened and asked JR and the marchers to tarry a while. He then began talking to S.D. Bandaranayake, urging him to remove his supporters. SD replied by saying that he had not brought anyone to stop the march and that he was only protesting non-violently to prevent the march as it was likely to disturb peace and trigger off violence if allowed to proceed unchecked.

The ASP then informed his superiors of the stand-off and placed a police party in between both groups as a buffer. He also warned the bystanders not to pelt stones. The mobs then ended their stoning but threw paper balls, trash, and sand at the dwindling number of marchers. Soon Police DIGs “Jungle” Dissanayake and Sidney de Zoysa arrived with a posse of armed policemen. After palavering with both parties, the senior DIGs asked JR to call off the march as a major breach of peace was anticipated.

JR was aware that his followers were deserting him and agreed to call it off. But he told the DIGs that he intended walking alone as a pilgrim to Kandy. A solitary pilgrim could not disrupt peace, JR pointed out. Dissanayake and de Zoysa then asked for time to consult higher authorities about JR’s request.

JR meanwhile squatted by the side of the road and told his supporters that he would continue his march and in an exhibition of ‘Gallery Sellama,’ said that he had written his will before starting out. JR requested his supporters to go back. However, predictably, the UNP supporters would not accept JR’s stance and urged that all of them retreat with honour.

Subsequently JR was told that the march was totally banned and no individual would be allowed to proceed on foot. So JR called off the march officially. S.D. Bandaranayake too was informed that the march was officially banned. SD then made a rousing speech to his supporters and got them to disperse quietly by 10:30 a.m.

Four buses of the Ceylon Omnibus Company were called and the remaining 70-75 UNP members including JR got in and started out for Colombo at about 12:30 p.m. Police escort was provided. Thus ended the infamous Kandy March led by J.R. Jayewardene. The UNP could not enter Attanagalle s intended thanks to SD.

Thereafter S.D. Bandaranayake was described on political platforms as the ‘Imbulgoda Veeraya’ or ‘Hero of Imbulgoda’. SD himself called it a people’s victory and said that he had initially blocked the march with only 12 people and that gradually hundreds of people had flocked in support voluntarily.

Elaborating about his action plan, SD said that initially he had placed five persons on either side of the road with sacks of thambili komba (king coconuts without kernels) to be flung at the UNP marchers while Dr. Chandrasena and the MP waited on the road. SD claimed that the people on seeing what was happening had voluntarily gathered in their hundreds in support. Some had come with their own “missiles” to be thrown at the marching UNP.

Having heard of the Kandy March from boyhood days and about how it was stopped at Imbulgoda by SD Bandaranayake, I was very curious to see the exact spot where it had happened. Though I travelled frequently along that road, I could never locate it. Finally in the ’80s, my friend Yapa Karunaratne from Divaina took me to the exact spot. Things had changed but I found myself able to visualise what may have happened then.

A watershed event

Though the march from Colombo to Kandy was blocked at Imbulgoda the scheduled UNP rally in Kandy was held as planned on 8 October. Both J.R. Jayewardene and Dudley Senanayake spoke at the meeting but the attendance was not large as anticipated.

Even though the Kandy march was aborted the event was a watershed in the sense that it focussed negative attention on the B-C Pact effectively. JR’s Kandy march was the forerunner that helped foment adverse public opinion against the B-C Pact. Ultimately Bandaranaike abrogated the pact unilaterally and symbolically tore up a copy of it in front of demonstrators.

When I was working for the ‘Virakesari’ as a staff reporter, I used to cover the then Ministry of State. Anandatissa de Alwis was Minister of State then (this was a full-fledged Cabinet ministry). Being an ex-journalist de Alwis used to get along well with scribes unlike some in power nowadays. Once I had read somewhere that Anandatissa too had participated in the Kandy march. When I asked him about it he seemed very embarrassed.

Anandatissa said that the move seemed very reasonable to him at that time but with the passage of time he had come to regret it. He said that many in the UNP felt remorse about it now. I then asked him whether the then President (JR) too felt that way, to which the diplomatic Anandatissa replied he did not know but personally opined that JR would be feeling sorry about it too.

But I do recall that JR was asked a question about the Kandy march at a rally in the Jaffna esplanade when he visited as Opposition Leader in 1975. JR was bold and candid enough to say that he would lead a similar march to Kandy again if similar circumstances warranted it. The then Jaffna SLFP Mayor Alfred Duraiyappa’s supporters then used it as a pretext to disrupt the meeting.

This then is the story of JR’s Kandy March and how S.D. Bandaranayake helped stop it and became known as the ‘Imbulgoda Veeraya’. Although the march itself was aborted within two days, the event has become embedded in the political memory of Sri Lanka.

‘JR’s Kandy March,’ as it came to be known, played a very negative role in souring ethnic relations in the island. The ultimate casualties were the B-C Pact in particular and ethnic harmony in general.

(This is an amalgamated version of two articles written earlier in 2007 and 2014)

(D.B.S. Jeyaraj can be reached at [email protected])