Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 6 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The proposals on motor vehicle duty which was implemented since 9 November has received mixed reactions.

The proposals on motor vehicle duty which was implemented since 9 November has received mixed reactions.

This article aims to explain the manner in which motor vehicle duty was calculated, and the manner in which it is now to be calculated, so the reader can make his own educated judgement on the merits and demerits of each system.

Ad Valorem tax is based on the value of goods. Customs in Sri Lanka took the manufactures invoice value as the transacted price (price paid or payable) to calculate dutyfor ‘agents1’ imports.

For ‘grey-market2’ importers, the assessment of value was more complicated, as their invoice did not originate from the manufacturer. For a long time, the ‘transacted value’ for grey market importers was ascertained by the agent’s valuation being deemed as transacted value. This process is allowed by the Sri Lanka Customs Ordinance and theGeneral Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT).

Grey market importers made representation to the Government that they didn’t want agents valuing their imports. As a means of appeasing this segment of the industry, the policy was changed whereby grey market importers values were based on the manufacturers’ website price of the import3. The grey market importer was given a 15% discount on this value. Therefore, customs arrived at the grey market importers ‘transacted value’ by taking the base website price and applying the 15% discount.

The concept of ‘Unit Rate’ (UR) was implemented in the budget of November 2014. The reason this system was implemented was that the Government felt that there could be instances where transacted value did not accurately capture the price paid or payable for the vehicle imported. The UR applied a flat rupee per cubic centimetre (CC), which is a universal measure of engine size.The UR multiplied by the size of the engine, gave the customs duty payable.

This system was somewhat complicated by the fact that the UR was used as a floor. That is, that customs duty payable was defined as eitherthe UR (based on CC) or the ad valorem rate (based on transacted price), whichever was higher.

In an ideal world, the system of levying customs duty based on transacted value is equitable. However, there are two elements in the Sri Lankan automotive industry that challenge the concept of ‘transacted value’.

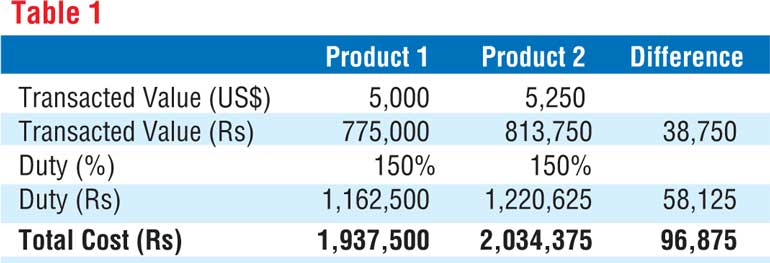

The first is that given the extremely high import duties levied on motor vehicles, the impact of the transacted value on the price of the good imported is huge. This point is explained using table 1.

The import duty on a car below 1,000 CC used to be around 150%. The above example shows Product #2 having a transacted value that exceeds that of product #1, by a mere $ 250. This value difference (of Rs. 38,750) leads to a duty increase of Rs. 58,125, which in turn leads to a cost difference of Rs. 96,875. This is a significant sum of money – around 5% of the cost of the vehicle.

The second issue that challenges the system of ‘transacted value’ is that a significant proportion of the motor vehicles imported into Sri Lanka are not imported through the local agent of the manufacturer of the vehicle. Thus, the invoice of the import does not always come from a credible source such as the manufacturer.

The issue with the hybrid system was that it gave grey market importers a 15% discount on website prices. The justifiability of this was debatable. Secondly, the grey market importer was only paying duty on a base vehicle, whereas the new car importer was paying duty on every option that was on the vehicle and captured on the vehicle invoice.

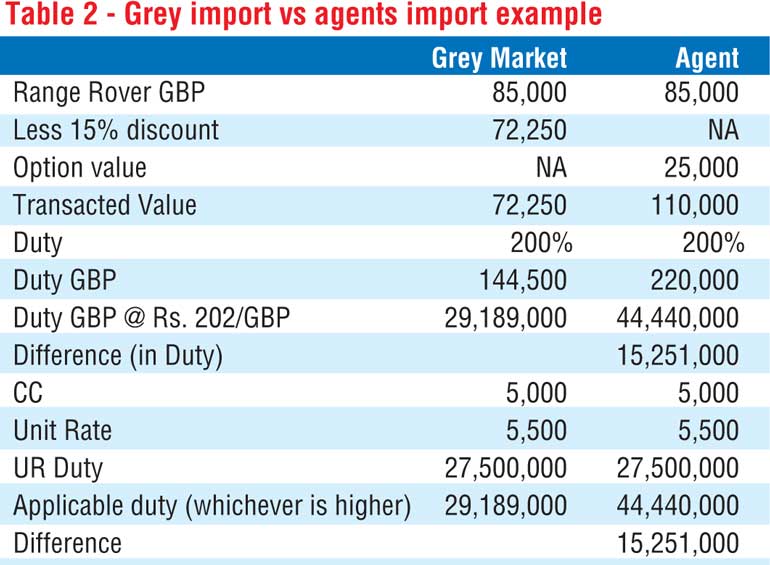

Again, if I may take the example of a base Range Rover, that has a UK web site price of GBP 85,000. Table 2 works out the duty payable by the grey market importer vs the agent.

Table 2shows an importer could have a benefit of Rs. 15 million (in duty alone)in the previous system. This is the reason for the significant increase in the import of luxury vehicles through the grey market during 2016. The potential revenue loss to the country was significant and estimated by the State Minister for Finance at Rs. 9 billion.

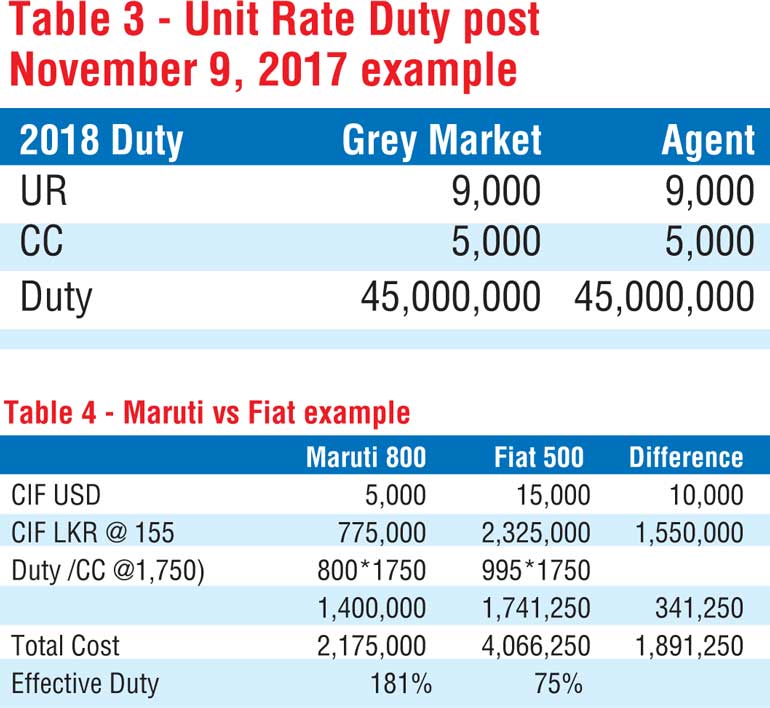

The present system of customs duty for motor vehicles is based on an Excise Duty that is computed on CC only. The same Range Rover example could be applied to the duty that is applicable from 9 November 2017.

The duty payable by any importer for an identical vehicle is identical. This has to be viewed as a positive for the present system. Further, where the duty was Rs. 29 million for the grey market importer and Rs. 45 million for the new vehicle importer, now the duty is Rs. 45 million for both importers.

An argument that can be levied against the present duty system isthat two products within the same CC category could have different effective rates of duty. This can be explained though the below example.

A Maruti 800 and a Fiat 500 are both vehicles below 1,000 CC (Petrol). These two vehicles are diametrically opposed to each other. The Maruti 800 is the first car for most Sri Lankan families. The Fiat 500 is an enthusiast sporty drive. The transacted values of the two vehicles are very different. However, the present duty system levies the same duty rate (per cc) on both of the above vehicles. Thus, the effective rate of duty (as a percentage of CIF) on the Maruti is 181% and on the Fiat is 75%. Opponents of the present duty regime argue that this is regressive and unfair.

On the other hand, one could evaluate the same example from the point of view of the Government thus; The Government is giving the user of the Maruti and the Fiat clean air, which both users are polluting. One may even argue that the level of pollution from the Maruti is more because the Fiat 500 would have a Euro 4 emission rated engine whilst the Maruti maybe Euro 2 (in Sri Lanka). The next cost to the Government is road space, and both vehicles occupy around the same road space. Thus, the Government could justify the present duty on the basis that from their perspective, the excuse duty they want for a 1,000 CC petrol engine is constant, no matter the CIF value of the vehicle.

engine whilst the Maruti maybe Euro 2 (in Sri Lanka). The next cost to the Government is road space, and both vehicles occupy around the same road space. Thus, the Government could justify the present duty on the basis that from their perspective, the excuse duty they want for a 1,000 CC petrol engine is constant, no matter the CIF value of the vehicle.

The industry in Sri Lanka has grown accustomed to the cost difference of a vehicle being a function of not only manufacturer’s cost, but, that as multiple of duty. This refers back to the first example where a manufacturer’s cost difference of Rs. 38,750 lead to a total cost difference of Rs. 96,875.

For a trader or customer in the UK, or US, where customs duty is negligible, the market price difference is merely a function of the manufacturer’s price and the seller’s margin.

Given the Price x Duty scenario, the cars that were competitive were the cheapest possible ones, and the agents that were successful were those who had access to these cost effective vehicles.

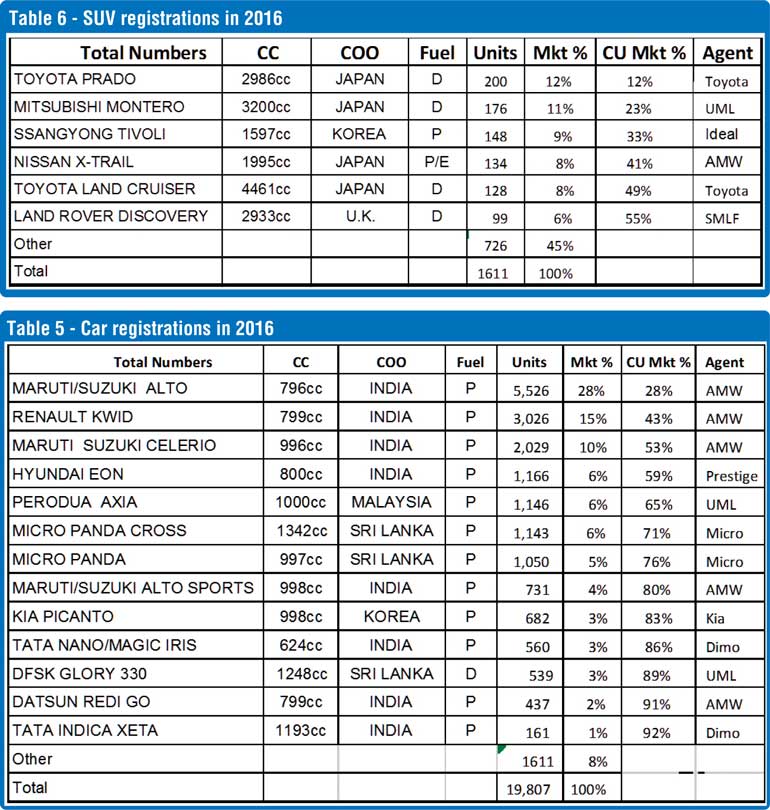

Table 5 shows that over 75% of the total vehicles sold in Sri Lanka have been imported through five agents and that these agents’ success has been because of very attractive CIF prices. The present duty system could broad base the industry.

Some the products listed above do not have ABS, Air Bags and are noncompliant to EU4 emission standard. The inclusion of these specifications will close the price gap between the top selling vehicles, and again benefit the industry by reducing its concentration amongst a few players.

Another issue that the present system of duty is bringing to the market is a significant benefit for hybrid engines and smaller engines. The duty on a 2,000 CC petrol hybrid engine is Rs. 10,000,000 whilst the duty on a 2,000 CC petrol engine is Rs. 12,000,000 and a 3,000 CC petrol engine duty is Rs. 27,000,000. This is a huge difference. On the other hand, the Government does have the prerogative to encourage smaller and greener engines.

The environmental problems caused by vehicular emissions that are being faced by Countries such as India and China should caution Sri Lanka to audit her levels of emissions as a matter of urgency and reduce emissions as much as possible.

Table 6 shows that the most popular SUVs being imported into Sri Lanka were those with competitive CIF values. It so happens that these SUVs have comparatively bigger engines. Table 6 shows the leading SUV products sold in 2016.

With the present duty system, these engines will probably not be marketable.

Because price was a factor of CIF x duty, the main strategy for competitiveness was the lowest possible CIF price (transacted value). Agents who had competitively priced products dominated the market. Permits were a distortion, where anyone below a price threshold had a duty benefit.

The budget of 2018 has shifted the goalpost from price to environmental conscience and safety. The Government is incentivising electric vehicles and hybrids and giving a clear indication that they do not want to encourage engines over 2,000 CC. This is very clear from the manner in which the duty cascades over the 2,000 CC threshold. The Government has also brought in a minimum safety standard, which is already applicable in most of the world.

The purpose of this analysis is merely to present facts before the reader, so the reader can make a judgement of which system of duty computation is more beneficial.

(The writer is the Managing Director of Innosolve Lanka Ltd., a company focused at promoting the adoption of electro mobility in Sri Lanka. Innosolve is a partnership between the MMBL-Pathfinder, the Peninsular Group Australia, the Tissa Jinasena Foundation and Sheran and Roshni Fernando – automotive industry specialists, with experience in growing brands such as Land Rover, Jaguar, Suzuki and Citroen.)

1 Importers who deal directly with the vehicle manufacturer

2 Importers who don’t deal directly with the vehicle manufacturer

3 This was complicated because of the multitude of websites all affiliated to a manufacturer, which quotes differing prices. It is further complicated by a plethora of models and model variations.