Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 11 May 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka would have been in a better position to tackle the economic fallout from the pandemic, had it achieved technology and innovation-driven growth by means of a knowledge-based economy – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe adverse effects on the Sri Lankan economy, which had already encountered multiple economic setbacks even before the pandemic. These include low economic growth, fiscal and balance of payments deficits and excessive debt commitments. The lockdowns and mobility restrictions imposed to prevent the spread of the pandemic have aggravated these economic problems.

The outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe adverse effects on the Sri Lankan economy, which had already encountered multiple economic setbacks even before the pandemic. These include low economic growth, fiscal and balance of payments deficits and excessive debt commitments. The lockdowns and mobility restrictions imposed to prevent the spread of the pandemic have aggravated these economic problems.

The economy contracted by 3.6% in terms of real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2020, recording the deepest recession since independence. Sri Lanka continues to remain in the lower-middle income country category, as her GDP per capita declined to $ 3,682 in 2020 from $ 3,582 in the previous year as a result of the economic contraction and the rupee depreciation against foreign currencies.

The real GDP growth is expected to rebound to 6.0% this year, and to reach 7.0% by 2025, as per the medium-term macroeconomic framework presented in the Central Bank’s Annual Report 2020. Given the subsequent waves of the pandemic and the country’s inherent growth constraints, the targeted economic recovery seems to be over-optimistic.

It should to be emphasised here that the country’s low level of investment efficiency in the past has had detrimental growth effects, and as a result, GDP growth had remained low even before the pandemic. An improvement in investment efficiency, therefore, is essential to attain the envisaged post-pandemic economic recovery.

Low investment efficiency in public sector projects

The conventional economic theory implies that investment generates high economic growth. Public infrastructure investment in developing countries, in particular, is expected to drive high economic growth since inadequate infrastructure is often viewed as a key bottleneck to economic progress.

Nevertheless, there is wide disagreement about the contribution of infrastructure investment on economic growth. Several empirical studies have found insignificant or negative impacts of infrastructure investment on growth possibly because public investment in developing countries often fails to generate productive capital due to corruption and the presence of “white elephants”.

A dollar’s worth of public spending often does not create a dollar’s worth of public capital, as argued by development economist, Lant Pritchett (1996). That means productive capital is sometimes not created at all. Even the created productive capital may be subject to implementation weaknesses and/or operational inefficiencies raising the cost higher than the minimum required to build the capital.

A good example of low quality/efficiency is a corrupt road construction project where the construction firm reduces the thickness of road surface to save money so to offer bribes to politicians and/or bureaucrats, as pointed out in the World Bank’s Policy Research Working Paper (October 2018).

Thus, a country’s GDP growth depends not only on the size of investment but also on the quality or efficiency of investment.

Sri Lanka’s low investment efficiency

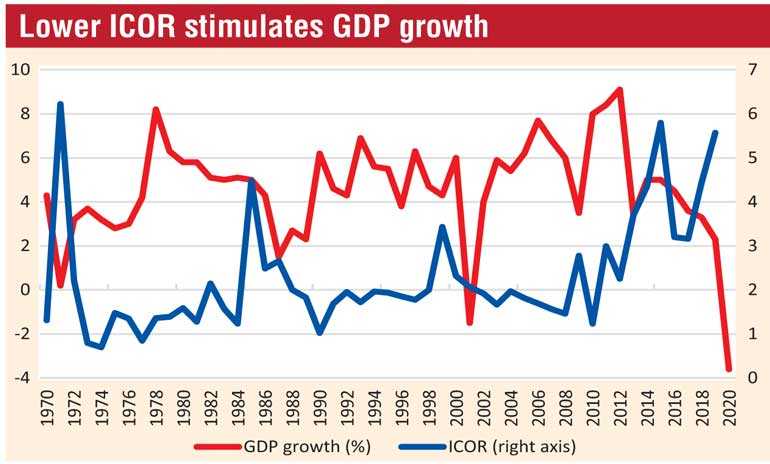

An economy’s investment efficiency or rate of return on capital can be measured by using the metric called the incremental capital-output ratio, abbreviated ICOR, which is the ratio of investment to GDP growth. It is equal to the reciprocal of the marginal product of capital. The higher the ICOR, the lower the investment efficiency. In other words, lower score of ICOR implies that investment is more efficient.

In the case of Sri Lanka, ICOR rose continuously from 2.99 in 2011 to 5.57 in 2019. This indicates that Rs. 2.99 worth of investment was needed to generate Rs. 1 of additional production in 2011 while Rs. 5.57 investment was needed for the same amount of additional production in 2019. This implies that the Sri Lankan economy has become less efficient in using capital.

The low investment efficiency is an outcome of several factors. A main reason would be that the rates of return on some of the major infrastructure projects such as highways are not immediately transmitted to production increases. Huge debt-funded investment allocated for certain less-productive public infrastructure projects in the recent past is also a matter of concern.

Prior project evaluation procedures would have prevented such inefficient investment. Cost escalation due to administrative irregularities including corruption too would have reduced investment efficiency to a certain extent, as discussed above.

Less-productive investment allocation

The bulk of the gross domestic capital formation (GDCF) is allocated in less-productive sectors such as construction and transport equipment. Investment in the construction sector accounted for 43% and transport equipment 14% of GDCF in 2020.

A similar pattern can be seen even with regard to Foreign Direct investment (FDI) of the enterprises under the Board of Investment (BOI). Housing, property development, shop office, and hotels and restaurants accounted for nearly 50% of FDI inflows in 2020. This indicates the poor quality of FDI which fell by 42% to $ 687 million in 2020.

In contrast, fast-growing countries heavily invest in the production processes with greater knowledge-inputs, and such investment helps to improve production efficiency. Investment in Research and Development (R&D) is essential for innovation of knowledge-intensive products and to move the country towards a knowledge-driven economy.

SL caught in middle-income trap

The concept of “middle-income trap” means that it is easier for a country to climb from a low-income to a middle-income economy than to make a big jump to a high-income economy.

Sri Lanka graduated from the low-income status to the middle-income status in 1998 taking advantage of the high investment efficiency emanated from the initial wave of economic growth. Low wages prevailed during the 1980s and 1990s made the economy more competitive for labour-intensive and low-tech manufacturing industries, mainly apparel industry. The resulting increase in export earnings provided a major impetus to surge economic growth up to around 2000.

Since then, the economy has continued to rely on low value added and low-tech industries, and as a result, the initial wave of economic growth ran out of steam. Eventually, a considerable deterioration in investment efficiency has been evident since 2001. As explained earlier, heavy concentration of investment in low knowledge-based sectors such as construction depressed the prospects of economic growth.

The average annual GDP growth was only 3.9% during the pre-pandemic period of 2013-2019, largely as a result of low investment efficiency. Thus, the pandemic alone is not responsible for the country’s growth slowdown.

Debt commitments of inefficient projects unbearable

Some of the major infrastructure projects implemented by the Government since the cessation of the conflict in 2009 were funded through heavy borrowings from foreign capital markets at commercial rates. These projects have not helped much to generate adequate production or export earnings due to poor investment efficiency. Hence, the Government now faces severe problems in repaying those maturing debts.

The total debt service payments exceeded Government revenue by 142% in 2020. Interest payments alone account for 72% of the revenue reflecting the gravity of the debt burden. Foreign debt service payments absorb one third of the country’s export earnings thus making the balance of payments extremely vulnerable.

How to improve investment efficiency?

It is not an easy task to improve investment efficiency at this critical stage, given the country’s long standing less-efficient production structure and the pandemic-hit economic activities.

The old-styled manufacturing ventures dependent on cheap labour and backward technology would not be sufficient to accelerate GDP growth. Labour and capital have to be used more productively, and in this regard, creativity and innovation become critically important.

An entirely new modus operandi of production process is required. Companies need to invest heavily in R&D to innovate high-tech products with own brand names, instead of merely assembling foreign products using imported technology and foreign capital.

Sri Lanka would have been in a better position to tackle the economic fallout from the pandemic, had it achieved technology and innovation-driven growth by means of a knowledge-based economy.

Looking forward, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity to reprioritise the development activities so as to improve investment efficiency and thereby to promote economic growth.

Whilst accelerating economic growth along those lines, sufficient attention should be given in the post-pandemic economic strategies to ensure macroeconomic stability so as to reduce the twin deficits in the fiscal sector and balance of payments keeping debt sustainability on top of the economic recovery agenda.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka. He is former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka and reachable through [email protected])