Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 20 July 2022 00:42 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Based on the high foreign loans obtained, in conjunction to Sri Lanka’s current economic status, there seems to be a strong indication that large-scale infrastructure projects severely indebted the State. If so, where did Sri Lanka go wrong?

Sri Lanka is going through a crisis of a magnitude that has never been witnessed in its economic history. The country is in disarray as people wait in lines to purchase essentials. Official reserve assets have plummeted to a $ 1,9201 million by May this year and the debt to GDP ratio has reached an all time high of 104.6% by 2021.2 The country is struggling to meet its domestic needs while having fallen into a debt default for the first time in its history. Why did Sri Lanka’s debt obligations escalate to the point of an economic crisis? Debt taken on to finance unproductive infrastructure is a part of the problem. (Debt was also taken to finance recurring expenditure including interest on past debts and subsidies to SOEs).

Sri Lanka is going through a crisis of a magnitude that has never been witnessed in its economic history. The country is in disarray as people wait in lines to purchase essentials. Official reserve assets have plummeted to a $ 1,9201 million by May this year and the debt to GDP ratio has reached an all time high of 104.6% by 2021.2 The country is struggling to meet its domestic needs while having fallen into a debt default for the first time in its history. Why did Sri Lanka’s debt obligations escalate to the point of an economic crisis? Debt taken on to finance unproductive infrastructure is a part of the problem. (Debt was also taken to finance recurring expenditure including interest on past debts and subsidies to SOEs).

Professor Amal Kumarage, one of the leading experts on transport infrastructure in Sri Lanka says, “Sri Lanka’s inability to service debts is a clear indication of inefficient infrastructure investment. Over 50% of the foreign loans in the past decade were for different transport infrastructure projects that have not delivered the anticipated economic outcomes. The professionals who promoted unfound optimism in economic analysis of these projects to please the political masters must come forward and accept their responsibility for contributing to this crisis.”

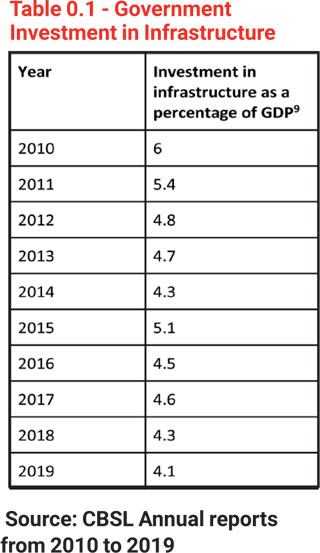

Since the end of the civil war, there has been a longstanding commitment towards developing large-scale infrastructure projects (See table 0.1).3 In the first eight months of 2020, Sri Lanka’s public expenditure on infrastructure development amounted to Rs. 98 billion.4 The Ministry of Finance aims to maintain public investment at an average of 5-6% of the GDP per annum till 2025.5 In terms of performance however Sri Lanka infrastructure falls short – it ranked 61 out of 141 under the overall infrastructure performance indicator by the ‘Global Competitiveness Report 2019’.6

Sri Lanka does have an infrastructure gap but it must invest in the right projects. The World Bank (2014) reports that Sri Lanka still needed $ 36 billion worth of investments to close its infrastructure gap, which amounts to 40.5% of the GDP in 2018.7 To avoid wasteful investments, Sri Lanka requires a fact-based project selection process and an optimised operation and maintenance system for existing large-scale infrastructure projects to close this gap.8 This would also reduce the country’s spending significantly. Among the numerous factors that fuelled this crisis, lavish investments in infrastructure of limited benefits seems to have played a crucial role.

Useful infrastructure projects should enable the best return to public investment with higher efficiency, increased safety and minimal environmental damage. It should also have a positive spillover effect which may range from generating employment and increased foreign direct investment to improved tax revenue.

How are large-scale infrastructure projects financed?

How are large-scale infrastructure projects financed?

In an effort to close the gap between existing and required infrastructure, the Government resorted to foreign loans. Foreign borrowing amounted to $ 1,710 million in the first eight months of 2021.10 This accounts to an increase of 16% of foreign financing disbursement in comparison to the previous year.11 Sri Lanka’s disbursement commitments consist of loans from multilateral agencies, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, and bilateral partners including China, Japan and India.12

With the provision of foreign loans to finance large-scale infrastructure projects among numerous other borrowings, Sri Lanka’s debt to GDP ratio has reached 104.6% in 2021. Based on the high foreign loans obtained, in conjunction to Sri Lanka’s current economic status, there seems to be a strong indication that large-scale infrastructure projects severely indebted the State. If so, where did Sri Lanka go wrong?

Lack of preliminary procedure

Taking on multi-million dollar investment projects is a complex task. Large infrastructure projects need to pass the test of utility in order to serve long-term demands before public money is spent.13

This means, thorough scrutiny is mandatory to enable the gains of large-scale infrastructure to be fully realised. This would include looking at the interest rates, grace periods and maturity periods provided. It also requires a comprehensive understanding of the type of loan provided. These can be achieved through conducting proper feasibility studies and risk assessments which will shed light on the project’s potential to service debt and its sustainability in the long run. For instance, loans obtained through multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank require a competitive bidding process to select a contractor.14 In contrast, projects funded by bilateral agencies are through tied loans.15 This means that bidding is limited to contractors from the lender’s country.16 During the period of 2005-2018, 28 out of 35 high value bilateral loans were procured without a competitive bidding process.17 The inability to gauge all available contractors at competitive rates to construct large-infrastructure potentially results in poor quality infrastructure at a cost of very high prices.18

The National Procurement Agency was a statutory body that handled competitive public procurement. However, right before the height of Sri Lanka’s investment spree in 2008, it was removed. In lieu of this, the Standing Cabinet Approved Review Committee (SCARC) was set up in 2010 to approve projects without public tendering or parliamentary approval. This creates additional concerns over the commercial viability of the project approved.19

Take for instance the Colombo Port City. Soon after SCARC approval, it was heavily criticised on the claims that its Environmental Assessment Impact was compromised. Further fuelled by the opposition from the fishing community, the project was temporarily suspended. The interim review of these concerns cost the Government $ 143 million as compensation. If proper procedures were followed, these costs could have been circumvented.20

Public infrastructure or political infrastructure?

Investments in large and complex infrastructure projects have also been a fertile ground for corruption, thereby increasing the risk of creating ‘White Elephants’.21 Rather than considering the economic value of obtaining loans from foreign lenders, governments utilise large-infrastructure projects as a tool to win the votes from the public. In the event such projects are not completed within their term, successive governments are inclined to halt its operations.22 This leads to unconsummated, poorly built infrastructure with limited benefits to the people.

Gaps in information: Calling for increased transparency

An effective mechanism of ensuring public money is spent to the best of its ability is to increase the access to information. There is a significant gap in data available to the public on large-infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka. For instance, a comprehensive breakdown of the loan amount, its repayment and interest rates are inconsistently provided in the Ministry of Finance Annual Reports. Selected projects financed through bilateral agencies have been completely omitted. Furthermore, information pertaining to the project’s appraisal and performance is not publicly available. This hampers the ability for the public to conduct an analysis on the investment made. The public must relegate to submitting Right to Information applications to the relevant implementing agency. However, comprehensive responses are rare. Nevertheless, investment on large infrastructure is a necessity. It has been assessed that 1 dollar worth of infrastructure investment can raise GDP by 20 cents in the long run.23 Furthermore, infrastructure development can facilitate trade and foreign direct investment.

In order to ensure that the benefits of each and every infrastructure project undertaken is fully realised, it is vital to set up a comprehensive framework with active public policy, transparent and competitive procurement, proper evaluation and an in-depth financing structure.24 Hard infrastructure should be accompanied by soft components such as policies and regulations in order to facilitate efficient performance.25 Therefore, a long-term plan for national infrastructure that is publicly available has the potential to pivot the feeding ground of corruption to the stepping stone of development.

Footnote:

1CBSL

2CBSL

3https://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/pb10_Infrastructure-Challenges.pdf

4https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/0d77beee-4e42-478b-9089-7f09be23a0e0

5https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/0d77beee-4e42-478b-9089-7f09be23a0e0

6https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/publications/annual_report/2020/en/13_Box_02.pdf

7Chinese Investment and the BRI in Sri Lanka

8https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/bridging-infrastructure-gaps-has-the-world-made-progress

9CBSL Annual reports from various years

10https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/16e9c6ec-7a13-4220-a8a7-1427c5d14785

11http://www.erd.gov.lk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=94&Itemid=216&lang=en

12http://www.erd.gov.lk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=94&Itemid=216&lang=en

13https://www.echelon.lk/a-circus-of-white-elephants/

14https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/VR_Eng_RR_Feb2021_Opportunities-to-Protect-Public-Interest-in-Public-Infrastructure-1.pdf

15https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/VR_Eng_RR_Feb2021_Opportunities-to-Protect-Public-Interest-in-Public-Infrastructure-1.pdf

16ibid

17ibid

18Key Informant Interview

19‘Locked in’ to China: The Colombo Port City Project

20‘Locked in’ to China: The Colombo Port City Project

21https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/VR_Eng_RR_Feb2021_Opportunities-to-Protect-Public-Interest-in-Public-Infrastructure-1.pdf

22https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/CHHJ8010-Sri-Lanka-RP-WEB-200324.pdf

23https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/four-ways-governments-can-get-the-most-out-of-their-infrastructure-projects

24https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/177093/adbi-wp553.pdf

25https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29823/infrastructure-supporting-inclusive-growth.pdf

(Janani Wanigaratne is a research intern at the Advocata Institute. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Tiffahny Hoole is a former researcher at the Advocata Institute. She can be contacted at [email protected]. The Advocata Institute is an Independent Public Policy Think Tank. The opinions expressed are the authors’ own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute.)