Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Monday, 5 April 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Geneva as an idea is firmly embedded in the Sri Lankan consciousness. For many Sri Lankans, especially the Sinhalese, it is an attack on national honour, a place where their vulnerability as a small island is exploited. For many Tamils and now Muslims, it is a place of hope. For human rights activists the world over, it is their forum

By Radhika Coomaraswamy

The Hindu: “Hey Geneva” laments Ajith Kumarasiri (musician, songwriter, and composer in Sri Lanka) in powerful Sinhala rhythm and blues. “We no longer kill.” “We don’t shoot anymore.” “Give us our island back.”

Geneva as an idea is firmly embedded in the Sri Lankan consciousness. For many Sri Lankans, especially the Sinhalese, it is an attack on national honour, a place where their vulnerability as a small island is exploited. For many Tamils and now Muslims, it is a place of hope. For human rights activists the world over, it is their forum.

The setting

The setting

The Human Rights Council in Geneva is a place where Sinhala and Tamil nationalisms meet, confront each other and fight countless shadow battles. In some of the side events of the Council, before the novel coronavirus pandemic, people have fainted, come to fisticuffs and been removed by UN security.

It is the place where both communities have large demonstrations next to the legless chair that reminds the Palais de Nations of the consequence of war. There are heated, blood-chilling speeches aimed at the supporters. For bystanders, much of this drama is quite unsettling.

The Government playbook with regard to the Geneva process at the UN Human Rights Council is to present it as an enormous power play full of double standards. It is seen as western countries ganging up on Sri Lanka for its closeness to China. Imperialism and neocolonialism remain in the frame. There is no government recognition that there may be any grievance or a victim. This just compounds the insensitivity.

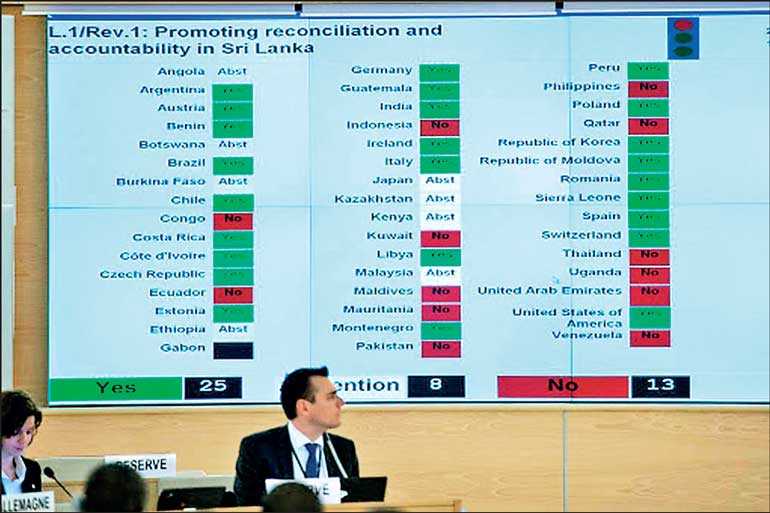

The Government’s aim this year was to have no resolution at all, while the major Tamil groups wanted the Human Rights Council to begin a pathway to the International Criminal Court. In the end, the resolution decided to create capacity at the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to collect, preserve and consolidate evidence not only on war crimes but also on other gross violations of human rights and serious violations of humanitarian law. There is no date or time period.

Geopolitics ‘plus’

Though geopolitics is the framework for decision making at the Human Rights Council, the actual process is more nuanced and may be described as geopolitics “plus”. Unless one acknowledges this “plus” factor, one will never understand the actual workings of the Human Rights Council. The activism, agitation and the momentum around a resolution created by this “plus” factor spills over and creates the atmosphere in which the resolution is adopted.

The “plus” factors around the Sri Lankan resolution were easy to identify. First came the legal experts of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, as well as the Special Rapporteurs and procedures who took very strong positions. The pivotal input by the Office was the Report of the High Commissioner on “Promoting Accountability and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka”. Michelle Bachelet as a High Commissioner, a torture victim, President, and a Minister of Defence, put her full weight behind the report. More than anything else, her report and words made the resolution inevitable.

In addition to the work of OHCHR, the Tamil groups nationally and globally were extremely active. But, it was Muslim civil society and the Muslim diaspora that made the difference for this resolution. Their passion, energy and sense of injustice filled the spaces. Despite heavy lobbying from Pakistan (the Coordinator on Human Rights and Humanitarian Issues in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, at Geneva), and from Bangladesh, after Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s visit in March, despite pressure from China and after the Rajapaksas made personal calls to OIC members, the large majority of Muslim countries still decided to abstain.

Elements to a global cause

Though the diasporas are always active, it is an international civil society made up of a whole array of disparate groups that dominate the agitational space of the Human Rights Council. These groups are often at odds with each other but act in solidarity when it comes to global causes.

Sri Lanka has again become a global cause. Once you get on the agenda of international civil society, it is difficult to get off. As Christine Schöwebel-Patel, the academic in international law and political economy, has recently written, there is a kind of “branding” in a communications sense that takes place and has severe consequences for country and community.

The events unfolding in Geneva are particularly disturbing because of their short-sightedness. In 2014, Sri Lanka faced a hostile Council and was an outlier in the international system very much like today. Most people have conveniently forgotten this history. The Resolution of the Human Rights Council in 2015 (https://bit.ly/3md0P8x) that Sri Lanka cosponsored after the government changed was to pull Sri Lanka out of the rut that it had fallen into. If that resolution were not passed, Sri Lanka would have had the evidence collection and preserving mechanism in some form by 2016.

The 2015 resolution accepted international best practices, an office for missing persons, an office for reparations, a truth commission and a judicial process for those guilty of serious crimes. At that time, the focus was on the need for a system that gave confidence to the victims. Victim groups were clear that a purely domestic process had failed them before. As a result, it was agreed to have a framework with an element of foreign participation.

Internationally, resolution 30/1 became a great success though victim groups thought it was a failure due to a lack of implementation. International hostility disappeared; Sri Lanka was dropped from international punitive agendas, became open to GSP plus (or the European Union’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus) and other trade and financial benefits and was welcomed back into UN peacekeeping. Despite its international success, 30/1 was reviled nationally as a resolution that “sold out the soldiers” — blurring the lines between the few who have committed war crimes and the large majority who have not.

Fundamentally, there was also a lack of understanding of what “co-sponsorship” meant and the enlightened self-interest that it entailed. Co-sponsorship has always meant accepting international standards while keeping control of the national process — the legislation to be enacted and the personnel to be appointed. By arbitrarily withdrawing from the resolution, Sri Lanka created the space for the Human Rights Council to create a new mechanism to collect and preserve evidence. This process is now independent of the Colombo government and will eventually have a life of its own.

The two sides

With this dedicated capacity at the OHCHR, the human rights issues regarding Sri Lanka will not go away. For many Sri Lankans, especially the Sinhalese, this is an outrage of double standards. There is real fury at what they see as global inequity. For many members of the minorities, opposition leaders, journalists, lawyers, victim groups and civil society activists who claim they are being harassed, prosecuted and intimidated on a daily basis by a surveillance state, there is relief to know that someone will be watching.

(Radhika Coomaraswamy is former Under Secretary General and Special Representative of the Secretary General on Children and Armed Conflict.)

(source: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/in-geneva-face-off-outrage-versus-hope/article34226409.ece)