Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 18 April 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This article is a follow up to a first article, ‘Serving citizens through effective delimitation of geographical boundaries in Sri Lanka’ (published in the Sunday Island and Sunday Times of 28 October 2018 and Daily Financial Times of 11 April 2019). It will attempt to explain why certain key principles of delimitation are critically important and how they can be best implemented.

The focus will be on the following principles, namely:

1)Consideration of two key factors, population and land: The delimitation process should address

a) total population within boundaries, recognising the needs of all citizens and b)total land within boundaries, recognising terrain differences and the need to safeguard all environmental resources.

2)Inclusiveness and Representativeness: The delimitation process should address equitably a) the well-being of each individual and b) the conserving of each unit of land.

3)Unbiasedness: The delimitation process should not be biased towards a) any sub-population or b) any land area. It should recognise the plurality and multi-cultural diversity of people living in the country. The needs of these diverse groups should be achieved to the best extent possible, without compromising on any other aspects of equitable representation. Similarly, this applies to the land.

4)Data consistency: The Delimitation process must be based on a consistent set of data for both population numbers and land that are comparable across the country.

As explained in the previous article referred to above, delimitation of geographical boundaries for any purpose, whether collection of information, administration, service delivery or election of citizens’ representatives, should be bound by the above principles.

In the case of electoral boundaries, under current laws, the delimitation process for all 3 levels of electoral representation, namely Parliamentary, Provincial Councils (PC) and Local Authorities (LA), begins with the existing administrative districts (districts). In Parliamentary and PC elections, electoral boundaries to select a representative, lie within a district. In LA elections, each LA lies within a district, while electoral boundaries to select representatives to each LA lie within that LA.

I believe that the primary objective of every right-thinking elected representative is to improve the wellbeing of each citizen and conserve each land unit within their electoral boundary. Under this premise, the delimitation process must ensure that all citizens are represented equitably.

The delimitation process is about best meeting the needs of its people and land, NOT about safeguarding the power and privileges of political parties, as some appear to believe! The delimitation process should strive for electoral boundaries that will enable representation of differing needs in different parts of the country, such as: the safety and security of communities of interest (minority groups by race or religion, female-headed households, disabled, etc.) to live in peace and harmony with others; the health and welfare of the vulnerable (differently-abled, infants and elderly), the quality of school facilities and teachers; access to employment and economic activities; infrastructure for commerce, industrial and agricultural activities; environmental protection against floods, erosion, landslides and other natural calamities, etc.

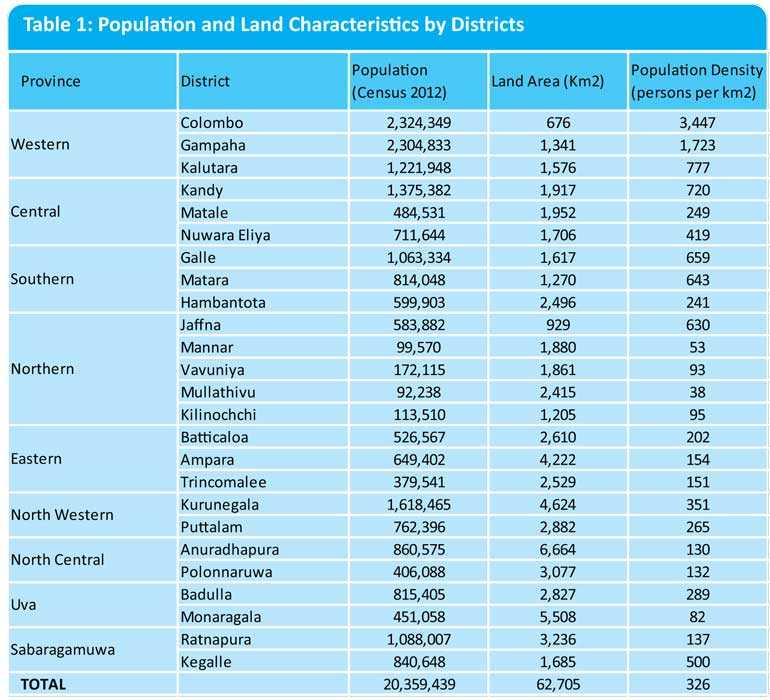

As in other countries, populations and land areas vary considerably among the 25 districts in Sri Lanka (Table 1). Such variations will always exist. In some areas the well-being of the population would require more attention and resources, while in others, the conservation of land resources would. The more urbanised districts (Colombo, Gampaha) have larger populations living in smaller areas, while the more rural districts (Anuradhapura, Moneragala) have smaller populations, but cover larger tracts of land, rich in forests, water and agriculture. The above principles need to be implemented after giving due consideration to such variations. These principles are already enshrined in existing legal provisions, as described below.

Basic factors to be considered for the electoral boundary delimitation process

1)Ensure equal voting strength for each member of the population within a district: This provides for inclusiveness, representativeness and unbiasedness. The district population comprises both below voting age and voting age population. However, the adults (voting age) need to represent the rights of the young (non-voting age) as well their own. Hence, it is the “total population”, rather than the voter population, that should be used as the population base for representation. As importantly, the delimitation process should target equal population per elected representative within each district (or LA), to ensure equitable representation. Practically, it is not always possible to obtain identical sub-population sizes for all electorates within a district (or LA). Hence, once the average population per elected representative (total population divided by the number of elected representatives) is determined, the delimitation process should minimise disproportion among electorates within a District (or LA) (i.e. balance the population distribution among elected representatives) by agreeing to a pre-specified tolerance level (say 5-10% above or below the average population per elected representative) to allow for any unavoidable variation. This principle is enshrined in Section 3A(4)(b)(i) of the Provincial Councils Elections (Amendment) Act No.17 of 2017.

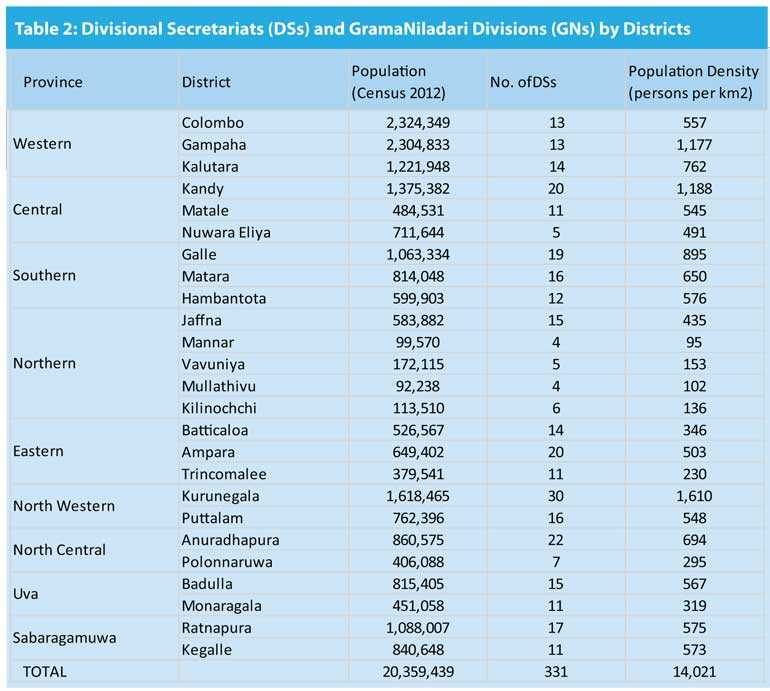

2)Recognise a) existing geographical features and b) existing administrative boundaries within a district: The delimitation process should focus on a) the specific environmental concerns in different areas and b) rationalise administration processes within the district. Delimitation needs to ensure that the population within any electoral boundary has access to its elected representative and vice-versa. This requires that an electoral boundary comprises a contiguous area of land such that all its inhabitants have convenient access, having given due recognition to the physical shape of a district, its contiguity and compactness, its geographical features and natural boundaries such as water bodies, ravines and mountains; ease of access to road networks and transportation; ease of access to communication networks and physically defined natural communities. This principle is enshrined in Section 3A(4)(b)(ii) of the Provincial Councils Elections (Amendment) Act No.17 of 2017. For example, we cannot expect citizens on one side of a mountain or deep ravine to travel to the other side to meet their elected representative – citizens should have representatives on either side. Further, all demographic information in Sri Lanka is collected within the smallest administrative units, namely, Grama Niladari Divisions (GNDs). Hence, it is practically important to use these GNDs as the geographical basis for delimitation, and combine them, without splitting, to form electoral boundaries. Since GNDs combine to form Divisional Secretariats (DSs) within Districts (Table2), it is best to try and keep DSs intact, to the extent possible. However, if DSs are required to be split to meet other specific criteria, they should be divided into groups of contiguous GNDs to form an electoral boundary.

3)Recognise a ‘Community of Interest’ within an area of a district: The delimitation process should give due consideration to any community of interest within an area that differs from the majority of population in that area due to a) shared racial or ethnic background, b) shared history and/or culture c) shared religion d) shared language e) shared socio-economic or income status f) shared economic activities g) shared gender or any other differentiating factor. This principle is enshrined in Section 3A(4)(a) of the Provincial Councils Elections (Amendment) Act No.17 of 2017. In this context, efforts should be made to ensure that these communities of interest have equitable representation in any elected body commensurate with their concentration in the population of that district, through the effective demarcation of electoral boundaries in those areas. For example, in the Batticaloa District, the people along the coast are mainly engaged in trading and business, whereas those living inland from the lagoon are mostly agriculturalists. Hence their needs vary, and in a best-case scenario, each should have their own representative. Similarly, in areas where there are a significant number of the population linked by a common religion, race or cultural tradition, but remaining a minority in the district, it would help for them to be geographically grouped to have a representative in the elected body to see to their needs, subject, of course to the conditions required to be met at 1) and 2) above.

4) Data consistency: In any country, the delimitation process has to use data from the most recent national population and land census conducted for that country. This ensures consistency and unbiasedness of the data collection. It is free of biases arising from different methodologies or different collection mechanisms. Historically, in Sri Lanka too, delimitation of electorates has always been based on the latest Census data. Sometimes, population may have migrated into, out of, or within the country for a variety of reasons (drought, floods, civil war, lack of employment opportunities, etc.) between the last Census and the time of delimitation, thereby rendering the census data somewhat different from the current ground situation. However, using more recent data collected by different sources using inconsistent definitions in different parts of the country (e.g. 25 different District Secretariats) would render the entire delimitation process more inconsistent than using less recent, but internally consistent, unbiased National Census data.

Effective delimitation of electoral boundaries that is undertaken within a clearly established framework and set of principles, can go a long way towards raising the confidence of our people in the electoral process and hopefully, attract young women and men of ability and integrity to provide courageous, visionary leadership in future Sri Lankan politics for the well-being of our people and the safeguarding of our environment.

(Since November 2015, the author, Ph.D., has been a member of the three-member Delimitation Commission, one of nine Independent Commissions appointed by the President under the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. She was also a member of the Delimitation Committee for Provincial Council Elections appointed by the President in October 2017. That Committee completed its task, within its mandate of four months, in February 2018. She served as Director of Statistics and later, retired as Assistant Governor from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka in 2007.)