Monday Mar 09, 2026

Monday Mar 09, 2026

Monday, 27 July 2020 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

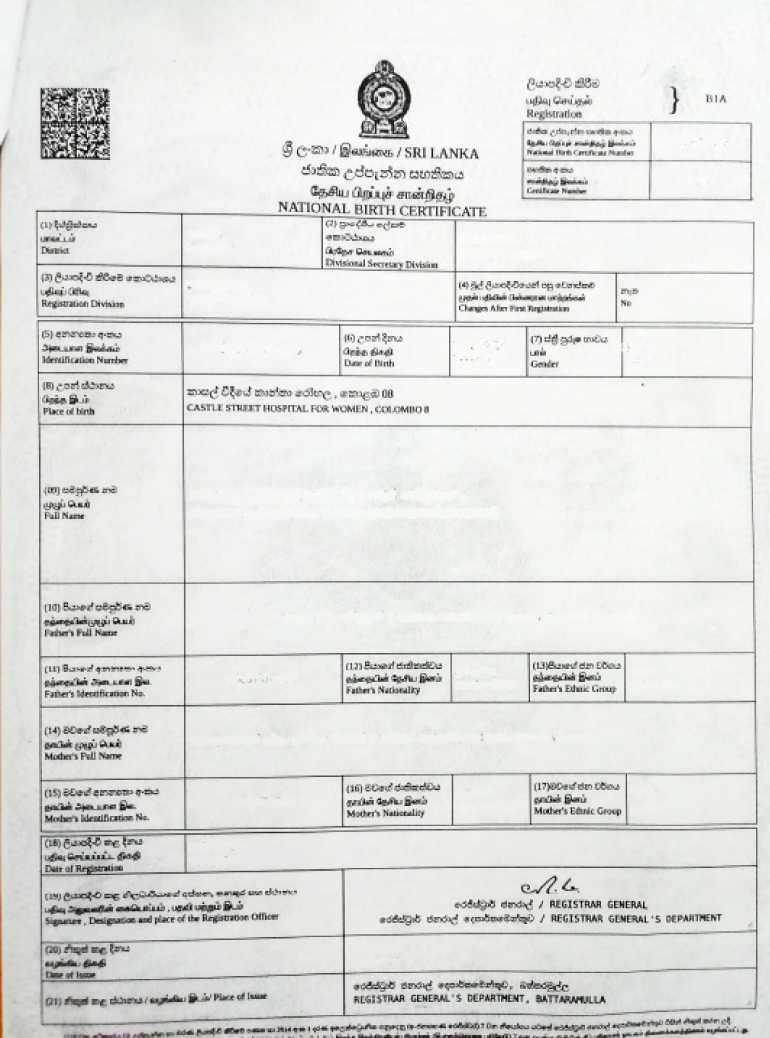

The Registrar General’s Department, established by the colonial government in 1864, maintains a low profile. Unusually, it found itself in some controversy in recent days. It announced changes in the format of birth certificates and within days walked them back when Colombo District candidate Wimal Weerawansa vehemently objected to the removal of race and religion from the certificate. Jehan Hameed, a prominent supporter of the ruling party, added her objection to religion being removed.

The changes also came under attack from an unexpected quarter, ethnic-justice activists. One tweeted that “if you belong to a ‘numerically-small ethnic group’, your identity is rarely ever officially recognised by the state and folded into one of the major groups by bureaucratic whim. I imagine this to be more hegemony/assimilation than any effort at meaningful inclusion.”

Ignorance personified

The new format was approved by the Eighth Parliament, of which Weerawansa was a member, as an amendment to Regulation 1 of 2014 under the Electronic Transactions Act 19 of 2006, and published in Gazette 2114/27 of 14 March 2019.

Weerawansa, who has been in Parliament since 2000, was surely aware that important matters such as the content of birth certificates are not decided on a whim of the Registrar General, against whom he directed his wrath. The Prime Minister who has been in Parliament for almost half a century should also have known. But according to reports he ordered race to be retained over the phone. What he should have ordered was the drafting of an amendment of the existing regulation.

But surely, we could expect better from Hameed, the civil society activists and the journalists who covered the story. Some simple fact checking would have been nice. Most people have a birth certificate (or two) in a drawer.

Had he bothered to check the birth certificates in his possession, Weerawansa would have found that religion has never been reported (does a new-born child have a religion?) and also that it was only the parents that had race listed against their names, not the child. If he took the trouble to refer to the Government Gazette on his smartphone, he would have found that the new format included new fields for nationalities of the father and mother, but also allowed their ethnic group to be shown.

Beyond Victorian mores

He may have also observed several very significant and progressive changes. The old format asked for the profession or rank of the father, but not of the mother. That is now deleted. The field “were the parents married?” is also gone.

Reasonable people would agree that these were retrograde elements included in our birth certificates by our former colonial masters. Why would one assume that the father has a rank or profession, but not the mother?

How could one stigmatise an innocent child through an official document as a bastard (the technical term for a child of unwed parents)? Even one who subscribed to Victorian morality, long abandoned by the British, would have to concede that the child bears no responsibility for the actions of her/his parents. Much of the credit for this reform must go to the Parliamentary Sectoral Oversight Committee on Women and Gender headed by Dr. Thusitha Wijemanne.

Some critics are concerned that the reduction of fields in the public certificate would result in loss of essential data and evidence: that proof of paternity would be lost or that we would no longer be able to know the ethnic composition of the population.

The former concern conflates data collection and information presentation. There is no reason to include all the information collected at the time of birth registration on the certificate. In many countries short-form certificates even exclude the parents’ names. But all the collected data exists within the Department and may be obtained using legal or administrative procedures. This is what should be done anyway, because a significant percentage of birth certificates are forged as may be seen from ongoing court cases against prominent individuals.

The latter concern is based on a misunderstanding. Ethnic composition is measured by the Department of Census and Statistics, not by going through individual birth certificates and laboriously adding up self-identifications of race. And as I said, the old form does not actually give the race of the registrant.

And as someone commented on Twitter, those who want race retained may care to explain why they do not argue for the reporting of caste too. Does not the absence of a field on caste in the certificate amount to the folding in of a numerically small group into a major group by bureaucratic whim?

Building block of e-government

A comprehensive and accurate population registry is an essential building block of e-government. This was why the regulations were promulgated under the Electronic Transactions Act. The key reforms in 2019 included provisions for the National Identity Number to be included in birth certificates issued since 2019, so that over time multiple numbers such as student numbers, birth certificate numbers, etc. could be eliminated. The new format also introduced security measures to make it more difficult to forge the certificates and to make it possible to remotely authenticate the documents.

By now, the attentive reader should have noted something unusual. Weerawansa and his ilk are protesting in 2020 July a regulation promulgated in 2019 March under the signature of Ajith P. Perera, the former Minister of Digital Infrastructure and Information Technology. Their protests are off by 16 months. It appears that this little storm was caused by someone doing the equivalent of inaugurating the same bridge twice. The pity is that this stratagem of giving the SLPP credit for an initiative of the previous UNF government triggered superfluous vituperation. One can only hope that the Ninth Parliament will not undo the good done by its predecessor as a result of this foolishness.