Wednesday Feb 04, 2026

Wednesday Feb 04, 2026

Wednesday, 1 November 2017 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

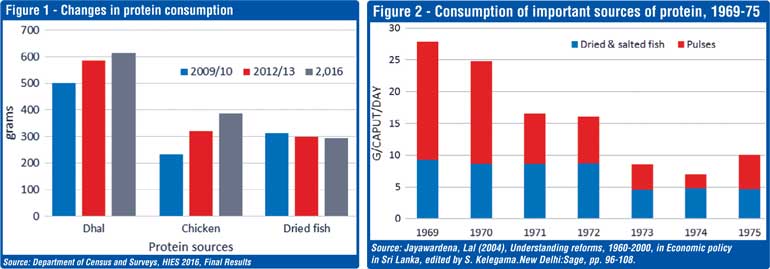

As the prosperity of a country (or a household) increases, it has been observed that protein consumption goes up. This appears to happening in Sri Lanka as demonstrated by the findings of the last three Household Income and Expenditure surveys, as shown in Figure 1.

As the prosperity of a country (or a household) increases, it has been observed that protein consumption goes up. This appears to happening in Sri Lanka as demonstrated by the findings of the last three Household Income and Expenditure surveys, as shown in Figure 1.

Chicken, it is well known, is one of the most popular protein sources among Sri Lankans. It has increased from an average of 233 grams per month per household to 387 grams by 2016. This was a 66% increase over six years.

Dry fish was for a long time a major source of protein for Sri Lankans. It is the only one which shows a small decrease over the past six years. It’s possible that it is being substituted by fresh fish, but unfortunately information on fresh fish consumption has not been provided in the recently issued summary report. For that, we will have to wait for the final report.

Consumption of dhal, another major source of protein, has also increased over the three survey periods, though not by as much as chicken.

Because we are marking the 40th anniversary of the 1977-78 economic reforms, it would be interesting to compare the protein consumption patterns prior to the reforms and now. A direct comparison is not possible because the data are taken from a report prepared by Dr. Brighty de Mel in 1978 using different units (daily per person, rather than monthly per household) based on an official socio-economic survey.

But the overall picture that she painted was a grim one, where protein consumption was more than halved during the socialist experiment of 1970-77. During that period, food imports were rigidly curtailed. For example, the import of dhal was altogether banned. Dry fish was only available through the State-controlled ration shops (cooperatives), through unofficial back markets flourished. The government decided what people ate, issuing dried sprats one week and a different kind of dried fish another week.

Dr. de Mel reported that the calorie and protein consumption of the poorest 43% of the population fell below the minimum levels of 2,200 calories and 40 grams of protein. Physicians active during that period have recounted that they observed cases of Marasmus and Kwashiorkor even in the city of Colombo.

So it appears that people are eating much better under the open economy than under the closed one. The numbers should be educative for those who still hanker for State control of the economy.