Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 18 January 2022 01:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

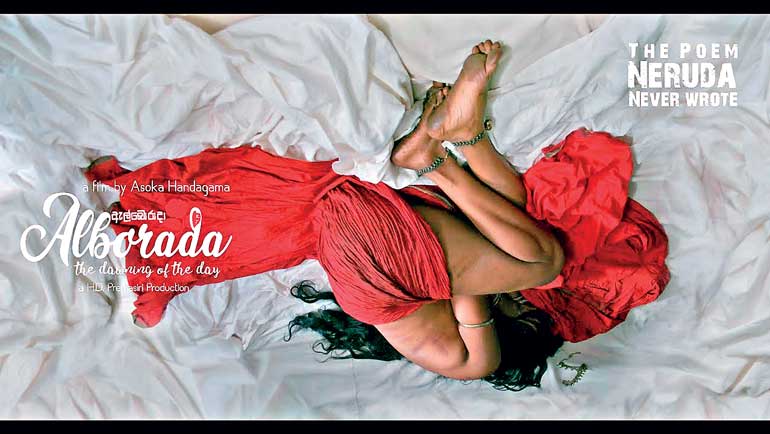

Alborada movie

|

|

Asoka Handagama

|

Handagama, the social disruptor

Asoka Handagama is famous for using art for disrupting society, which is believed to be sane, serene, and free from evil. But society is like a lake; on the surface, it is calm, eye-catching, and mind soothing. Beneath that calmness, there are all those decomposing matters that give at the end a different flavour to the waters of the lake. They are odorous, ugly, and contrasting aesthetic feelings.

A romantic artiste may just portray the lake or society on what he sees on the surface, ignoring the contrasts and contradictions deep beneath it. But Handagama has been different and had the audacity to sear that surface calmness, penetrate deep into it, and portray that ugly side which people usually do not want to see. All his previous cinematic, theatrical, and television works have done this in one way or the other. For this reason, Handagama is branded as an anti-society artiste.

Alborada: The story of Pablo Neruda

His latest cinematic work, Alborada, has done this in a different way. Based on a short tryst of the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda, in colonial Ceylon – as modern-day Sri Lanka was called at that time – Handagama has questioned how the caste system had been used as an economic as well as a repressive weapon by many. The caste system here is not the one that had been practiced by majority Sinhalese in colonial Ceylon. It is the most repressive and unacceptable system that had prevailed among the minority Tamils at that time.

Within this repressive system, women are the ones who are economically and sexually exploited by others. Alborada is the story of such a woman belonging to the lowest caste in the contemporary caste system among the Hindus – the untouchables. When this incident was taking place in colonial Ceylon in 1930s, in the neighbouring India, the untouchables were being shown the path to salvation by Henry Steel Olcott and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar by converting them to a casteless religion, namely, Buddhism. Strangely, this social reform did not take place in Ceylon, the country that takes pride in being the protector and guardian of the Theravada Buddhism.

Pablo’s unexpected arrival in Ceylon

Pablo’s unexpected arrival in Ceylon

The plot in the movie is as follows. The lead character in Alborada, Pablo Neruda, (played by Spanish actor Luis Jose Romero) is posted as the Chilean consul in colonial Ceylon in 1929. As Handagama has presented it, he had come to Ceylon from colonial Burma to relocate himself to escape another traumatic experience he had had there. That experience had been related to a love affair with an expatriate woman in Burma – Josie Bliss – whose character is being played by the French-Vietnamese actress, Ann-Solenne Hatte.

According to Pablo, Josie has been a tigress in the bed – a panther in Burmese terminology – demanding the impossible from her lovers with a knife in her hand. The young poet who romanticises love gets scared and flees for his freedom. Thus, on one fine day, Pablo arrives in Colombo empty handed to take the position of Chilean consul in the consulate. He rents a house in suburban Colombo located on the seashore facing the vast Indian Ocean. He is welcome to this house by his male servant, Rathnaigh, (played by Sri Lankan actor Malcolm Machado), a high caste Hindu who is eternally in fear of being polluted by the physical contact of an untouchable, a man or a woman.

Therefore, his first briefing to the master was that he too should not get polluted by such physical contacts because purification from such a pollution involves a long and hazardous process. But what Rathnaigh does not know is that his master is a free-thinking man and these Indian caste taboos are alien to the cultural or religious values upheld in Chile. Hence, Pablo was free from such taboos and could see a woman as a woman and not as a conveyer of social pollutants.

Fear of sex tigresses

Handagama has been careful in building Pablo’s character on these lines. Thus, Pablo is posited as a foreigner with an independent and liberal approach to people living in this part of the world. When he was riding a rickshaw to attend a function hosted by some Europeans, he passed a procession of local dancers and drum beaters. He gets late to the function because his instinct forces him to follow the procession and find out more about that tom-tom beating. He rushes to the function profusely apologising for being late saying that he had had a wonderful experience of a native cultural procession.

He is disappointed by the rude and crude reaction of fellow Europeans. But he makes two encounters at the function. One is the meeting of a local photographer called Lionel played by Sri Lankan actor Dominic Keller. This meeting helps Pablo to learn more about the native ways of life. The other meeting which Handagama arranges for him is more important to build his character. In that meeting, he meets a French woman living in Ceylon called Patsy and played by Sri Lankan dramatist Nimaya Harris. She offers an opportunity to Pablo to test his sexual prowess which he fears has been lost due to the traumatic encounter with the sex tigress in Burma.

In a later episode, Pablo mixes up with a group of low caste people who had gathered at a local bootlegger’s joint to drink and make merry on the pay day. They had been untouchable because they had belonged to the Sakkili caste, the carriers of toilet baskets from toilets used by the rich in Colombo. Pablo dances with them as if he is one of them, to the annoyance and repulsion of his male servant Rathnaigh. At the end, Pablo is fully contended but Rathnaigh pushes him to the sea in an apparent attempt at cleansing him of his pollution. Or it may be a warning that Rathniagh does not tolerate his mixing with the untouchable Sakkilis.

Falling in love with a statue

This liberal attitude which Handagama has cultivated in Pablo helps him to go for the final coup de grâce. Pablo sees a statue of Parvathi that had belonged to the previous occupant of the house dusting in a corner of the room. The bare-breasted Hindu goddess in shining ebony enamours him instantly. He is secretly in love with Parvathi and does some bizarre things like taking the statue to the bed. Patsy visits him to establish a long-term sexual relationship with him, but he rejects her. He treats with the same crude attitude the Sri Lankan lady living in the opposite house. Her attempts at winning his heart through choice Sri Lankan foods are also foiled.

In a twist of irony, his Burmese sex tigress, Josie, follows him to Ceylon. The fear of sex with such an insatiable sex tigress remerges within him and he hides from her. After a few unsuccessful attempts at joining his life, Josie leaves Ceylon for good. Handagama has portrayed Pablo’s character as someone who is waiting for the arrival of a Parvathi in living form to have his inner sex drive satiated.

Seeing Parvathi in a Sakkili woman

Then, one day early in the dawn, he sees the silhouette of a Parvathi walking toward his toilet with a bucket held securely with one hand on head and a cleaning broom swinging in the other. It is still dark but the heavy winds blowing from the sea remove the cloth hanging loosely over her shoulders from time to time exposing the silhouette of a Parvathi-type breast to the spying Pablo. That was the Sakkili girl, played by Sri Lankan actress Rithika Kodithuwakku, who had been commissioned to clean his toilet and remove the soil-filled bucket every morning.

Despite Rathnaigh’s warning that she is Sakkili and untouchable, Pablo finds himself falling in love with this newfound Parvathi. This growing carnal desire has overwhelmed him so powerfully that no force in this world or above can stop him now. He is determined to possess this Parvathi and satisfy his desires. It seems that such a blissful experience is beyond the plane of human mortals but something to do with divinity.

An experience that was never repeated

The sociological principle established here needs further elaboration. Sakkili women are vulnerable and can be economically exploited by high caste males. But concerning sexual exploitation, they are safe from the males of higher castes because they are considered untouchable and defiled. But this does not apply to male species of other ethnicities or religions. When it comes to satisfying their carnal desires, these male species do not see any social taboo. Pablo belongs to this category.

Pablo describes this in his memoirs as follows: “One morning, I decided to go all the way. I got a strong grip on her wrist and stated into her eyes. There was no language I could talk with her. Unsmiling, she let herself be led away and was soon naked in my bed. Her waist, so very slim, her full hips, brimming cups of her breasts, made her like a thousand-year-old sculpture from South India. It was the coming together of a man and a statue. She kept her eyes wide open all the while, completely unresponsive. She was right to despise me. The experience was never repeated.”

Dramatised end of an episode

In reality, the experience was never repeated. But in Handagama’s movie, the dramatisation of the post-rape events meant it could not be repeated. In the movie, the Sakkili girl who feels that she has been defiled by this foreigner runs away from the room like a woman possessed by a spirit. She jumps into the sea in an attempt at cleansing her body now believed to have been defiled. She cannot face the folk of her community, however much they are considered low caste and untouchable. They too have values and she has unwittingly defiled those values. Hence, her body may be cleansed but not the spirit filled with guilt and repulson. She goes down in the sea leaving the viewers aghast. It seems that she has drowned herself.

There is a greater commotion in Pablo’s household. Rathnaigh who witnesses the entire episode with nauseating repulsion leaves Pablo’s house in disgust. At this crucial hour, Pablo who thinks that he has joined divinity is being abandoned by mortals. It is therefore his turn to be possessed by the devil. He runs to his outdoor toilet, picks the cleaning broom left by the Sakkili girl, and starts cleaning the toilet like a mad man. He picks the soil-filled bucket, places it on his head the way it is carried by the Sakkili girl and walks to the sea. It is as if to punish himself for the defilement he has entailed on the Sakkili girl.

This is a highly dramatised event in Handagama’s movie. But the story does not end there. The Sakkili girl, believed to have been drowned, rises from the sea as if a Goddess reemerging from the waters. But it is not a Goddess, but the very same Sakkili girl in the same dress and body painting. What has Handagama conveyed by this? Though one cruel episode relating to a vulnerable woman has ended, she is still there with the same vulnerability and opening opportunities for repeated cycles of exploitations.

Disrupting society

How has Handagama disrupted society through Alborada? He has questioned the validity of the sane side of society which commits evil things in the name of divinity. This is not only relevant to economic or sexual exploitations. It is relevant to politics and governance too. In politics, leaders justify the evil things they do by claiming that they have simply carried out the wishes of divinity. Society does not want to discuss these events in public. Hence, such discussions are confined only to whispers or private communications.

Deviating from this self-restriction, Handagama has brought the taboo subject to open discussion. Some may agree with him, while some others may vehemently object to him. But the job of the artiste is to portray what is not openly seen. Handagama has done this job to full perfection.

Nimaya Harris and Luis J. Romero

Rithika Kodithuwakku as Sakkili Woman

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)