Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 23 June 2018 00:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Cinematic journey of maestro Lester James Peries – Part 2

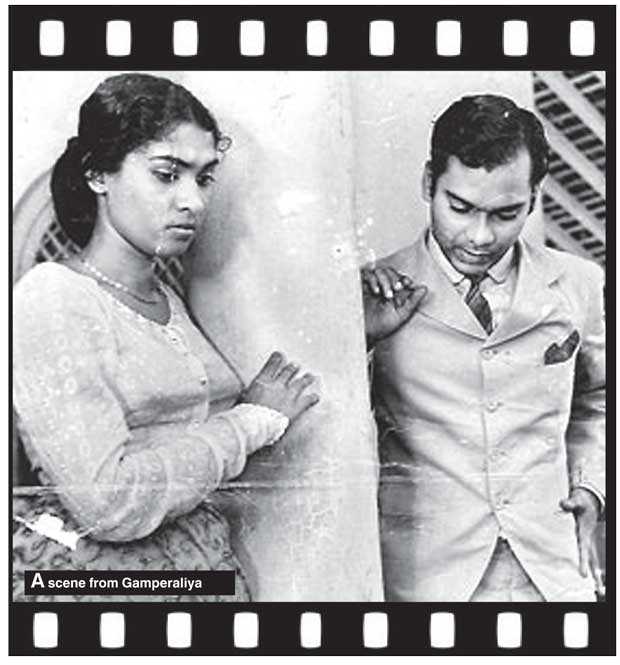

‘Gamperaliya’ (Changes in the Village/Changement au Village) was the third feature film made by ace director Lester James Peries. It was released on 20 December 1963.The film was based on the famous novel of the same name written by the doyen of Sinhala writers, Martin Wickramasinghe. The movie hailed as a milepost in the evolution of Sinhala cinema remains an outstanding example of how a great novel could be made into a great film by a great director.

‘Gamperaliya’ (Changes in the Village/Changement au Village) was the third feature film made by ace director Lester James Peries. It was released on 20 December 1963.The film was based on the famous novel of the same name written by the doyen of Sinhala writers, Martin Wickramasinghe. The movie hailed as a milepost in the evolution of Sinhala cinema remains an outstanding example of how a great novel could be made into a great film by a great director.

Gamperaliya placed Sri Lanka then known as Ceylon on the global cinema map by winning gold at two international film festivals. The film won the ‘Golden Peacock’ award for Best Film at the third International Film Festival of India (IFFI) held from 8 to 20 January 1964 in New Delhi. It also won the Golden Head of Palanque award in 1965 at the Mexico International Film festival held in Acapulco. Gamperaliya won silver at the 1967 Cork Film festival in Ireland. Prior to its public release, ‘Gamperaliya’ also competed at the third Moscow International Film Festival in July 1963 and won a Merit certificate.

Gamperaliya placed Sri Lanka then known as Ceylon on the global cinema map by winning gold at two international film festivals. The film won the ‘Golden Peacock’ award for Best Film at the third International Film Festival of India (IFFI) held from 8 to 20 January 1964 in New Delhi. It also won the Golden Head of Palanque award in 1965 at the Mexico International Film festival held in Acapulco. Gamperaliya won silver at the 1967 Cork Film festival in Ireland. Prior to its public release, ‘Gamperaliya’ also competed at the third Moscow International Film Festival in July 1963 and won a Merit certificate.

‘Gamperaliya’ also harvested many awards at home. The Sarasaviya awards are the Sri Lankan equivalent of the Oscars. The event was introduced by the Sarasaviya weekly published by the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. (Lake House). The first Sarasaviya film festival was held on 9 May 1964 at the Asoka theatre in Colombo.

All Sinhala films produced between 1960 and 1963 were up for awards. Only five awards were given, for Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Script Writer at this pioneering event. ‘Gamperaliya’ swept the boards, winning four out of five. Producer Anton Wickremasinghe accepted the award on behalf of ‘Gamperaliya’ for Best Film. Lester James Peries was Best Director. Regi Siriwardena was Best Script Writer and Punya Heendeniya Best Actress. Only the Best Actor prize eluded ‘Gamperaliya’. It went to D.R. Nanayakkara for ‘Sikuru Tharuwa’.

Cinema of contemplation

Before venturing to write about ‘Gamperaliya’ in this series, I would like to emphasise a particular point of a personal nature. I am an aficionado of Sinhala films in general and those of Lester James Peries-Gamini Fonseka in particular and have derived immense pleasure viewing them over the years. However, a drawback I suffer from in this respect is my comparative lack of fluency in Sinhala.

Before venturing to write about ‘Gamperaliya’ in this series, I would like to emphasise a particular point of a personal nature. I am an aficionado of Sinhala films in general and those of Lester James Peries-Gamini Fonseka in particular and have derived immense pleasure viewing them over the years. However, a drawback I suffer from in this respect is my comparative lack of fluency in Sinhala.

Although I can talk and understand Sinhala to a reasonable extent my reading and writing skills are rather poor in the language. I have only learnt ‘Practical Sinhala’ for three years from C.S. Weerainghe, J.S. Amarasekara and W.G. Mandawela respectively at STC Mt. Lavinia. Moreover my Sinhala has become rather rusty after relocating to Canada nearly three decades ago.

This however has not deterred me in watching, appreciating and relishing the films of Lester James Peries. A most notable feature of his films is the economy of dialogue. It is well-known that Lester’s characters do not speak much on screen. They convey much of their emotions and feelings through their gestures and gazes and through the eloquence of silence.

Critics and reviewers have described Lester’s films as the cinema of contemplation. He relies extensively on images as opposed to words to tell his story. As Lester himself famously said, films are not made in the Sinhala or Tamil languages but in the language of cinema. Thus my inadequacy in Sinhala was seldom a problem in enjoying Lester’s films.

Based on the greatest novel in Sinhala

In the case of ‘Gamperaliya,’ the film is based on what is regarded as the greatest novel in Sinhala. It is the first of three novels known as the Koggala Trilogy the other two being ‘Kaliyugaya’ and ‘Yuganthaya’. It was in 1944 that ‘Gamperaliya’ was first published. It was a departure from the prevailing trend of romantic novels ushered in by writers such as Piyadasa Sirisena and W.A. Silva.

Prof. Ediriweera Sarachchandra in his book ‘The Sinhala Novel’ first published in 1950 hailed Martin Wickramasinghe’s masterpiece as realistic fiction and praised it for the authentic portrayal of rural society. He called it the first Sinhala realistic novel. Gamperaliya in essence outlined the changes in Sinhala society and class conflict through the fluctuating fortunes of a family and related characters.

Prof. Sarachchandra then wrote: “‘The Changing Village’ is a true tale of village life than anything that has appeared before. In its stark realism, it introduced us to characters whose attitude of life and mode of behaviour are unique. He presents these new types of humanity to us with a deep understanding of their psychology and the environmental conditions that served to produce such a psychology.”

Prof. Sarachchandra then wrote: “‘The Changing Village’ is a true tale of village life than anything that has appeared before. In its stark realism, it introduced us to characters whose attitude of life and mode of behaviour are unique. He presents these new types of humanity to us with a deep understanding of their psychology and the environmental conditions that served to produce such a psychology.”

Decades later Prof. Wimal Dissanayake in his ‘Sinhala Novel and the public sphere’ observes thus about Gamperaliya: “The relationship between the decaying feudal class and the rising middle class is far more complex and culturally nuanced than normal sociological text -books would have us believe. Martin Wickramasinghe as a sensitive novelist and insightful public intellectual was fully cognisant of this fact… ‘Gamperaliya’ charts with great subtlety the experience of social change. Change comes to the peasant society but much of it is endogenously generated. It is not a simple case of the external world impinging harshly on a placid and self -enclosed world… What Martin Wickremesinghe is seeking to do in this novel is not only reflect change in rural life but also to define it and evaluate it and give greater depth to it. In doing so, he anatomises the experience of change among the peasantry and their social structure in a remarkable prescient manner displaying a wholly admirable narrative authority.”

Usually I would have had to depend upon expert commentary or reviews in English about a Sinhala novel to comprehend what it was all about as I am not competent enough in Sinhala to read a novel or play in that language. But as far as Gamperaliya is concerned I am fortunate in the sense that a very fine translation of the book is available in English. The book translated by academic Lakshmi de Silva and the author’s son Ranga Wickramasinghe is published by Sarasa Ltd., which I believe is affiliated to the Martin Wickramasinghe Trust. In fact I bought ‘Gamperaliya’ and many other works of the master in English from the Trust office on Kirimandala Mawatte at Nawala in 2013. The publishers have used ‘Uprooted’ as title of the book translated in English though other writings have referred to it in English as ‘Changing Village’ or ‘Village Upheaval’. Since Lester’s film is called ‘Changes in the Village’ in English, I shall use that in writing this article.

“Chekhovian” writings

The term “Chekhovian” has often been applied to some of Martin Wickramasinghe’s writings as well as some films made by Lester James Peries. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov born on 29 January 1860 was a prolific Russian writer and playwright.

Prof. Richard Mullin in writing about Chekhov says: “These (Chekhov’s) stories often deal with the difficulties landowning families experienced following the abolition of serfdom (an institution close to slavery) in 1861. With this change, and the development of a new capitalist economy in the Russian countryside, many gentry families did badly, proving to be poor business people. They were viewed, and often viewed themselves, as a declining, historically outdated class of people.” ‘Gamperaliya’ in that sense was perfectly Chekhovian.

Cabinet Minister Dr. Sarath Amunugama is arguably the foremost intellectual among the present set of Sri Lankan Parliamentarians. He is also an accomplished author and a reputed connoisseur of the arts, cinema and literature. Dr. Amunugama, a long-time friend of Lester, delivered the Lester James Peries memorial lecture in 2012. In that lecture Dr. Amunugama described Lester James Peries as the ‘cinematic interpreter’ of Martin Wickramasinghe and observed that ‘Anton Chekhov is the bridge between Wickramasinghe and Lester’. Here is the relevant excerpt:

Cabinet Minister Dr. Sarath Amunugama is arguably the foremost intellectual among the present set of Sri Lankan Parliamentarians. He is also an accomplished author and a reputed connoisseur of the arts, cinema and literature. Dr. Amunugama, a long-time friend of Lester, delivered the Lester James Peries memorial lecture in 2012. In that lecture Dr. Amunugama described Lester James Peries as the ‘cinematic interpreter’ of Martin Wickramasinghe and observed that ‘Anton Chekhov is the bridge between Wickramasinghe and Lester’. Here is the relevant excerpt:

“Whatever some nationalist thinkers say, almost all the distinguished creative artists and literary figures of Sri Lanka have been largely influenced by their readings of great works of western literature. Martin Wickramasinghe, Sarachchandra, Gunadasa Amarasekera and Siri Gunasinghe have all been influential by classical western writers. We will later see the strong impact of outstanding pre-revolution Russian writers, particularly Anton Chekov, on Wickramasinghe which links him to his cinematic interpreter Lester, whose works have been described by international critics as ‘Chekovian’. Anton Chekov is the bridge between Wickramasinghe and Lester… Wickramasinghe was a voracious reader. He read the Russian classics of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekov and Gorky. That fed his inherent humanism which grew out of his close observation first of village life in South Sri Lanka and later of the metropolis of Colombo, which was being transformed by the beginnings of native capitalism.”

The ‘Gamperaliya’ story

Martin Wickramasinghe’s novel is located in Koggala, his birthplace. Koggala is a coastal village 139 Km to the south of Colombo in the Galle District. It is bounded on one side by the Indian Ocean and on the other by the Koggala Lake into which the tributaries of Koggala Oya flow. Martin Wickramasinghe focuses on the fluctuating fortunes of a prominent family belonging to the landed gentry in Koggala. It is basically the story of Muhandiram Don Adrian Kaisaruwatte (Muhandiram was an honorary title bestowed by the British colonial rulers) and his wife, children, sons-in-law, neighbours and servants. The period depicted is the early 20th century. The transformation of society at large and values is reflected through the changes in the village which in turn are narrated through the family’s experiences. Since Lester himself excelled in relating stories of changes in society through the microcosm of the family, the novel ‘Gamperaliya’ provided ideal raw material for the type of film making desired by the director.

Gamperaliya was first published in 1944 at a time when the Sinhala novel realm was under the dominant influence of Piyadasa Sirisena and W.A. Silva. The popular Sinhala novels of that time were generally classified as romanticised fiction. Martin Wickramasinghe’s ‘Gamperaliya’ was a significant departure from the prevailing trend. It was considered to be in the realistic fiction genre.

‘Gamperaliya’ received favourable reviews as a significant step in the growth of Sinhala fiction and was reasonably popular with readers. However the literary merits of the novel received full recognition in 1950 when Prof. Ediriweera Sarachchandra published his seminal work ‘The Sinhalese Novel’. Sarachchandra examined the Sinhala novel applying principles of modern literary criticism. In his estimation Martin Wickramasinghe’s ‘Gamperaliya’ was rated very high for introducing the aesthetic of realistic fiction.

As I mentioned earlier I consider myself very fortunate indeed to be able to read ‘Gamperaliya’ in English. The translation has been praised by many bilingual reviewers as being of excellent quality. The English version written simply yet vividly and eloquently captivated me and provided great insight. The fate of traditional society values in the face of changes brought about by modernisation is an island-wide phenomenon in Sri Lanka. Although I am not a son of the southern soil I could easily relate to the book and the film.

I have been watching the film on DVD repeatedly and re-reading the book avidly in order to write about ‘Gamperaliya’. I am enjoying it immensely. The vicissitudes of the Koggala Kaisaruwattes strike a responsive chord transcending ethnicity, religion, region or country. The changes in life of a declining feudal family narrated with great understanding and empathy has a universal appeal. One is easily able to understand why Lester James Peries wanted to make a film out of this novel.

Prof. A.J. Gunawardene in his book ‘LJP: Lester James Peries – Life and Work’ quotes Lester thus: “‘Gamperaliya’ had all the qualities I had been searching for – it rang so true in the depiction of characters, their relationships, their social background. It had insight a sense of compassion, a profound humanity. Its character leapt off the pages not as romanticised caricatures but as living human beings moulded by their social background… In a sort of way, despite my Anglicised roots, my Roman Catholic isolation, I had discovered my roots through Martin Wickremasinghe. Filming ‘Gamperaliya’ became an obsession with me.”

Waiting for a break

Lester James Peries had burst upon the Sinhala film scene with his path-breaking ‘Rekava’ in 1956. The film in its initial run crashed at the box office. However the film brought fame internationally for the director. Though the film covered its losses through international earnings and subsequent screenings in Sri Lanka, an unfair label ‘Box Office Poison’ had been pinned on Lester James Peries. Thus no film producer wanted Lester to direct a film despite the laurel of ‘Rekava’ being the first Sinhala film to be shown at the prestigious Cannes film festival. Lester had to languish without a film for more than three years before he got a break to make a film again.

Lester James Peries had burst upon the Sinhala film scene with his path-breaking ‘Rekava’ in 1956. The film in its initial run crashed at the box office. However the film brought fame internationally for the director. Though the film covered its losses through international earnings and subsequent screenings in Sri Lanka, an unfair label ‘Box Office Poison’ had been pinned on Lester James Peries. Thus no film producer wanted Lester to direct a film despite the laurel of ‘Rekava’ being the first Sinhala film to be shown at the prestigious Cannes film festival. Lester had to languish without a film for more than three years before he got a break to make a film again.

This was in the form of Cinemas Ltd. owned by K. Gunaratnam. Cinemas was celebrating its 10th anniversary in 1960. Gunaratnam wanted a “prestige” film to mark the occasion. Gunaratnam who owned a string of cinema theatres was a shrewd cine mogul who knew what the audience wanted to see. ‘Cinemas’ had made several money spinners like ‘Sujatha,’ ‘Suraya’ and ‘Dosthara,’ which were basically re-makes of Tamil and Hindi films. It was Lester’s friend and ace cinematographer Willie Blake who had persuaded Gunaratnam to try out Peries as director. Lester accepted the offer and made the film ‘Sandesaya’ (The Message) in an entertaining mode with dances, songs and fights. The film was a roaring success with audiences and clicked extremely well at the box office.

Lester James Peries had now made two films one of which was artistically acclaimed while the other proved to be a commercial success. Yet there were no offers to Lester. After spending a few years in fruitless anticipation, Lester resolved that he himself would go ahead and take the initiative in making a film instead of waiting for an offer.

By this time a close relationship had blossomed between Lester James Peries and Sumitra Gunawardena. Sumitra was the niece of Sri Lanka’s ‘Father of Marxism’ Philip Gunawardena and his brother Robert. Sumitra had met Lester first in Paris when he was going to Cannes to screen ‘Rekava’. She was interested in films and treated Lester as a guide and mentor. After completing further studies in the UK and France, Sumitra returned to Sri Lanka. She worked as an assistant director on ‘Sandesaya’. Now Lester and Sumitra wanted to make a film independently.

Both ‘Rekava’ and ‘Sandesaya’ were based on stories written by Lester. The ‘Rekava’ script was written by Lester James Peries and K.A.W. Perera. The ‘Sandesaya’ script was written by Lester James Peries, Benedict Dodampegama and K.A.W. Perera. Now Lester thought of filming an original Sinhala novel or novella. After scouting around for a suitable literary work, Lester wanted to film ‘Gamperaliya’ for reasons which have been stated earlier.

Convincing Martin Wickramasinghe

Lester met Martin Wickramasinghe at his Nawala residence and sought his approval to film ‘Gamperaliya’. The great man was delighted. The Sinhala film industry was developing fast and several novels and stories by Sinhala writers had been made into films. Apparently the Sinhala literary colossus had been somewhat disappointed that none of his books had been made into films whereas quite a few of his distinguished contemporary W.A. Silva had been made into films like ‘Kele Handa,’ ‘Radala Piliruwe’ and ‘Daiva Yogaya’.

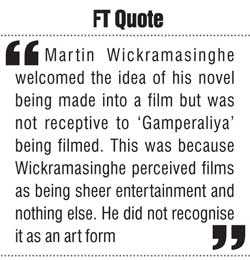

Martin Wickramasinghe welcomed the idea of his novel being made into a film but was not receptive to ‘Gamperaliya’ being filmed. This was because Wickramasinghe perceived films as being sheer entertainment and nothing else. He did not recognise it as an art form. He felt a film could not be made out of his Gamperaliya which was a realistic novel devoid of cinematic ingredients. He felt a serious novel could not be an entertaining film. He tried to persuade Lester James Peries to make a film out of his historical novel ‘Rohini’ and not ‘Gamperaliya’. Incidentally when Lester was searching for scripts before filming ‘Rekava,’ Martin Wickramasinghe’s ‘Rohini’ had also been perused.

Lester relates the essence of his encounter with Martin Wickramasinghe thus in A.J. Gunawardene’s book: “Martin Wickramasinghe looked every inch the intellectual – the face as though chiselled by a sculptor, the forehead high domed, the hair leonine. A man of great dignity and courtesy. He confessed that his knowledge of cinema was very limited. He could only recall some Tarzan films from the days of his youth.

“When I mentioned that we were interested in filming ‘Gamperaliya,’ he looked genuinely puzzled. To him as to most literary men of his generation, the cinema meant simple, uncomplicated stories, action, heroics, romance and glamour. I suppose he was convinced that a serious novel, dealing sensitively with the complexities of human behaviour and human relationships, would be far beyond the resources of the cinema.

“Wickramasinghe proposed that we consider his ‘Rohini,’ a very popular historical adventure story, instead of ‘Gamperaliya’. That I managed to persuade him that cinema had advanced to a point where it was capable of translating the greatest works of literature without castrating them was an achievement on my part. I wonder if I truly convinced him.”

“Wickramasinghe proposed that we consider his ‘Rohini,’ a very popular historical adventure story, instead of ‘Gamperaliya’. That I managed to persuade him that cinema had advanced to a point where it was capable of translating the greatest works of literature without castrating them was an achievement on my part. I wonder if I truly convinced him.”

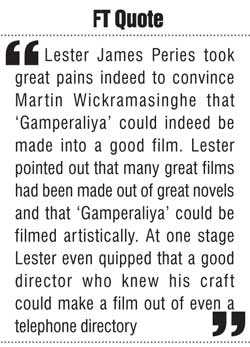

Lester James Peries took great pains indeed to convince Martin Wickramasinghe that ‘Gamperaliya’ could indeed be made into a good film. Lester pointed out that many great films had been made out of great novels and that ‘Gamperaliya’ could be filmed artistically. At one stage Lester even quipped that a good director who knew his craft could make a film out of even a telephone directory. Peries also enlisted the services of renowned journalist, writer and literary critic Regi Siriwardena in this effort.

Roping in Regi for the ‘Gamperaliya’ project was a master stroke on the part of Lester as Martin Wickramasinghe had a very good opinion of Siriwardena who was regarded as the finest interpreter of Wickramasinghe’s writings to English newspaper readers.

I had the good fortune of interacting closely with Regi Siriwardena during my stint at the International Centre of Ethnic Studies (ICES) between 1985-’88. Regi told me of how he wrote a synopsis first and later a preliminary screenplay of the novel to show Martin Wickramasinghe how the film would be made. The great man was pleased and gave the green light for ‘Gamperaliya’ to be filmed.

Success at last

Ultimately ‘Gamperaliya’ proved to be a great film made from a great novel by a great director. But Lester James Peries had to surmount several obstacles before succeeding in his mission. Initially the biggest problem was a simple one which besets most creative film makers – finance!

As Lester himself told A.J. Gunawardene later: “Filming ‘Gamperaliya’ became an obsession with me. But where was the money to come from? Sumitra and I had gone to every producer, every businessman with pretensions to art, but we had failed.”

After repeated failures to find a producer to finance ‘Gamperaliya,’ Lester and Sumitra tasted success finally by finding a businessman ready able and willing to help produce ‘Gamperaliya’. The would-be producer of ‘Gamperaliya,’ like the novel’s author, was also a Wickremesinghe. Although a namesake, he was no relative of the writer. The commercial entrepreneur cum patron of the arts who was prepared to produce Gamperaliya was none other than the legendary Anton Wickremasinghe!

NEXT: Shooting Gamperaliya

(D.B.S. Jeyaraj can be reached at [email protected].)