Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Tuesday, 22 June 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Central Bank, which is responsible for sustaining price and economic stability, should insist that the Government ensures fiscal discipline adhering to strict budget targets, instead of lavishly accommodating the Treasury’s cash requirements and ridiculing the much-needed structural reforms as neoliberal nonsense

Neglecting the urgent need to reduce the budget deficit so as to restore economic stability, a few days ago, the Government decided to defer the fiscal rules that were introduced way back in 2003 until the year 2030.

Neglecting the urgent need to reduce the budget deficit so as to restore economic stability, a few days ago, the Government decided to defer the fiscal rules that were introduced way back in 2003 until the year 2030.

The budget deficit rose to 11.1% of GDP in 2020, and it is most likely to be over 12% of GDP this year in the backdrop of revenue shortfalls caused by pandemic-hit economic activities. The fiscal deficit, compounded by the tax cuts effected in 2019, is the root cause of excessive money supply growth and debt accumulation in recent times aggravating macroeconomic instability, as I reiterated many a times in this column previously.

Distancing itself from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Central Bank has turned to international capital markets to raise borrowings. Since last year, even such borrowings have been constrained by the country’s weak debt sustainability. Therefore, foreign loans through bilateral swap arrangements with China, India and Bangladesh have become the next choice, as I explained in last week’s column (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Swap-from-Bangladesh-A-loan-or-an-investment/4-719236).

Shying away from IMF

The Government, on the advice of the Central Bank, is determined to avoid seeking financial assistance from the IMF to overcome the balance of payments difficulties.

The irony is that the Government is now compelled to adopt bits and pieces of IMF’s policy prescriptions, even without any financial agreement with the Fund.

A good example is the recent fuel price increase. Regular fuel adjustment is a usual conditionality in IMF policy packages. With such conditionality Sri Lanka could have realised better budgetary management uplifting her credit worthiness in foreign capital markets.

Central Bank still in search of an alternative policy approach

The Central Bank continues to deny assistance from the IMF arguing that the conditionalities attached to such assistance are not compatible with the Government’s home-grown alternative economic policy strategy.

At his very first Monetary Policy Review meeting held in December 2019, Central Bank Governor Prof. W.D. Lakshman stated: “In the present context of subdued growth and development, continuing poverty pockets despite poverty alleviation policies of several decades in the past, and prevalence of unemployment and underemployment at worrying levels, fiscal and monetary authorities and decision makers in different sectors of the economy are confronted with the challenge of searching and identifying alternative policy sets of greater efficacy than the neoliberal policy sets we have been working on so far. I hope to be able to make my contribution on this search for this alternative, working together with the other authorities.”

He further mentioned: “This is the time of important changes in Sri Lankan development policy and practice. Questions are being raised extensively about the validity and relevance of ‘Washington Consensus’-type or neoliberal-type of policies to achieve the desired goals of inclusive, sustainable and shared development. This questioning may also apply to central banking nowadays. I am extremely excited about the opportunity I have gained at a time like this to make my active contribution to Sri Lanka’s search for an alternative policy approach to achieve the desired development objectives.”

Many moons have passed since the above declaration, but the alternative policy set is yet to see the light of day.

EFF agreement abandoned

The Yahapalana Government entered into a three-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement with the IMF in June 2016 for an amount equivalent to SDR 1.1 billion (around $ 1.5 billion, or 185% of the country’s quota) to support Sri Lanka’s economic reform agenda.

The present Government abandoned the EFF arrangement in 2019 without drawing its last tranche amounting to around $ 200 million.

EFF agenda

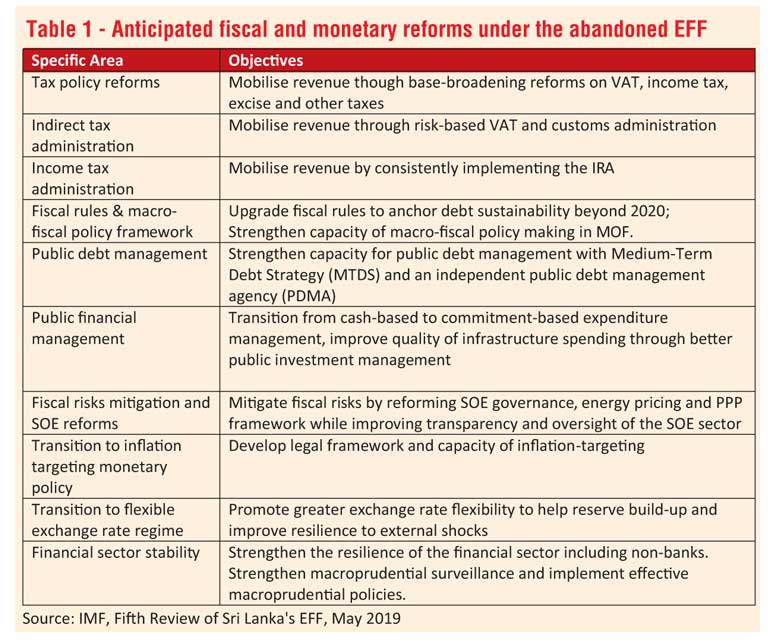

The anticipated fiscal and monetary reforms under the now defunct EFF are summarised in Table 1. Fiscal consolidation targeting a reduction in the overall fiscal deficit was the linchpin of the EFF program. Rebuilding tax revenues through a comprehensive reform of both tax policy and administration were key in this regard. These were to be supplemented by steps toward more effective control over expenditures and putting State enterprise operations on a more commercial footing.

It was also expected that a clear commitment to exchange rate flexibility would improve the external payments position while allowing the Central Bank to rebuild foreign exchange reserves and focus more closely on its key mandate of price stability.

Fiscal deterioration

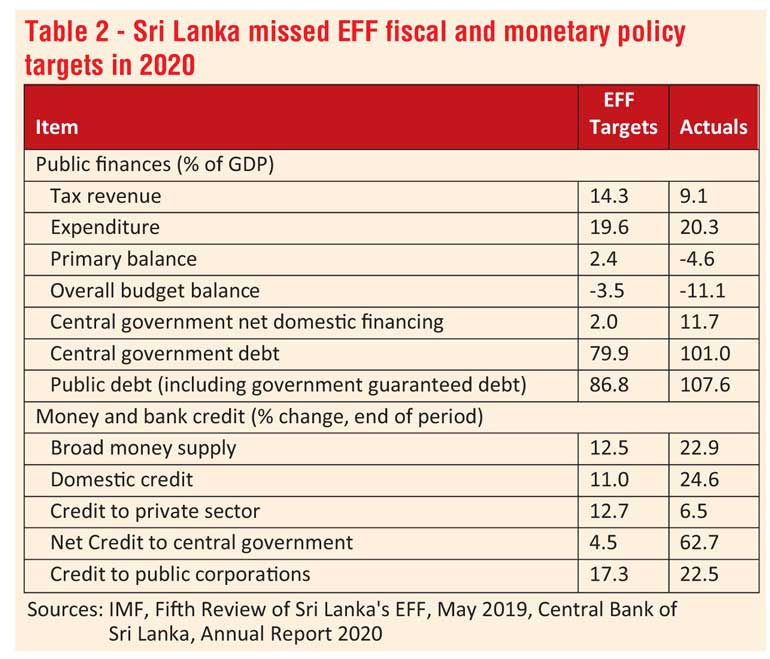

The fiscal and monetary situation worsened by 2020, as shown in Table 2. The budget deficit widened to 11.1% of GDP in 2020, in comparison with the much lower deficit of 3.5% envisaged in the EFF programme.

This was largely an outcome of the significant decline in tax revenue in 2020. Following the Presidential election in November 2019, the Inland Revenue Act was revised so as to provide a wide range of concessions to tax payers, without considering the adverse fiscal implications for economic stability.

Accordingly, personal income tax rates, tax-free thresholds and tax slabs were relaxed significantly with effect from 1 January 2020.

Also, Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) tax on employment receipts, Withholding Tax and Economic Service Charge were removed effective from the above date. Downward revisions were made to the Value Added Tax and Nation Building Tax to stimulate business activities.

Continuing the downward trend, the tax revenue is likely to be even lower this year which would widen the budget deficit to around 12% of GDP.

As a result of the larger borrowing requirements to finance the widening budget deficit, the Government’s debt to GDP ratio rose to 101% in 2020, and when the Government guaranteed loans are included the ratio goes up to 108% of GDP.

Fiscal targets postponed until 2030

Making matters worse, a few days ago, the Parliament approved an amendment to the Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Act of 2003 to further relax the fiscal rules. Accordingly, the Treasury guarantees provided for bank loans to state-owned enterprises and private entities are to be raised from 10% to 15% of GDP.

Also, the ratio of debt to GDP target envisaged in 2013 is now shifted to year 2030. When the Act was initially approved in 2003, it was targeted to reduce the gross Government debt to 85% of GDP by the year 2006, and reach 60% by 2013. It was also expected to maintain the budget deficit at 5% of GDP.

The successive Governments have never attempted to achieve the stipulated fiscal targets during the last 18 years since the enactment of the Act. As a result, the fiscal situation has deteriorated over the years aggravating the debt burden to unsustainable proportions by now.

Excessive money supply growth

Excessive money supply growth

The broad money supply rose by 22.9% in 2020, as against the EFF target of 12.5% (Table 2). Direct purchase of Treasury bills by the Central Bank owing to undersubscribed auctions led to increase reserve money (notes and coins), which provides the monetary base for commercial banks to create credit by multiple times.

A major reason for the excessive money supply growth is the rise in bank credit to the Government and public corporations. Net bank credit to the Government rose exorbitantly by 62.7% in 2020, as against the EFF target of 4.5%. In the backdrop of difficulties encountered in raising foreign loans in the capital markets, domestic bank credit has been extensively used to finance the budget deficit.

On the contrary, private credit slowed down partly due to the pandemic-affected economic setback.

The amendment to the Monetary Law Act, which was in the EFF agenda with a view to provide greater independence to the Central Bank by permitting it to adopt inflation targeting monetary policy, is abandoned now.

Energy price increase without a reform package

Although there is aversion to IMF-styled economic adjustments at the policy level, the Government is now compelled to unwittingly implement some of the conditionalities contained in the so-called neoliberal reform packages to avoid fiscal disaster. A good example is the recent price increase of fuel prices.

In an effort to strengthen governance and transparency of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the energy pricing reform was a key policy component of the EFF programme which was abandoned in 2019. A fuel pricing formula, linked to a 3-month average of the Singapore Platts index, was introduced with a view to reduce the losses of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) caused by administratively determined prices. This fuel adjustment formula was scrapped in 2019.

It is reported that the Energy Ministry has obtained Cabinet approval last week to raise foreign loans amounting to $ 1 billion in order to repay CPC’s local debt to State-owned banks. This will further worsen the foreign debt situation.

IMF’s rapid financing instrument untapped

Contrary to official claims defying IMF assistance, the Fund’s Director of Communications, Gerry Rice announced in May last year that they had received a request from the Sri Lankan Government for emergency financial support, under the rapid financing instrument to replace the EFF. He confirmed that the IMF was having discussions with the Government in this regard. These discussions do not seem to have brought fruitful results yet.

However, Sri Lanka is likely to receive $ 800 worth reserves under a new allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the IMF without any conditions.

Little hope for economic stabilisation

Given the postponement of fiscal adjustments until 2030, economic stability seems to be a distant reality for Sri Lanka. In effect, the much-overdue fiscal adjustments are conveniently passed down to the next generation.

The money supply has already been rising at a rapid pace owing to Central Bank’s easy credit policy characterised by fiscal dominance over monetary policy threatening price stability. The resulting deterioration of the rupee value is reflected in the depreciation of the currency vis-à-vis US dollar in recent months.

The adverse effect of rupee depreciation is already felt in the energy sector which led to raise retail fuel prices last week. This will have spill over effects on the entire economy spiralling cost-push inflation. The poorest are going to be the worst hit by impending consumer price increases.

The Central Bank, which is responsible for sustaining price and economic stability, should insist that the Government ensures fiscal discipline adhering to strict budget targets, instead of lavishly accommodating the Treasury’s cash requirements and ridiculing the much-needed structural reforms as neoliberal nonsense.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable at [email protected])