Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 7 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Waruna Singappuli CFA

By Waruna Singappuli CFA

The current Sri Lankan economic policy emphasises two salient points:

1.Boosting Government tax

revenue by increasing taxes

2.Reducing Government debt

The esteemed economists and IMF seem to be in agreement with this approach. I disagree with both and am of the view that the strategies built on the above will lead us deeper into the economic wilderness.

Starting from the Super Gains Tax in 2015, the increase in VAT from 11% to 15% to the latest proposition of “debt repayment levy”, the focus has been on introducing more taxes. Corporate tax rates have also been increased for a number of sectors.

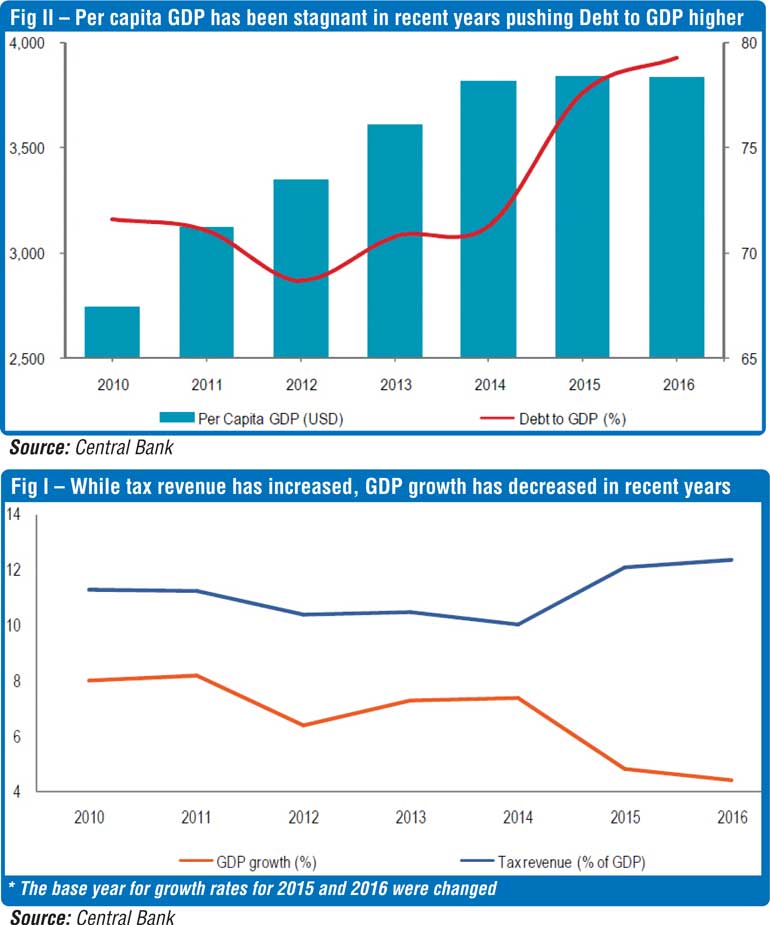

The simple logic is, higher taxes impede investment and curtail consumption. Therefore, the impact would be felt in terms of economic growth as investment and consumption are two key components of economic growth. The statistics clearly show the impact (refer Fig I). GDP growth has been anaemic at less than 5% over the last two years. In fact, it could even be lower than 4% in 2017, which is the lowest growth since the ending of war in 2009. As a result, per capita GDP has been trapped at just over $

3,800 since 2014 and it is unlikely to be significantly better in 2017 or 2018.

While tax increases may not be the only reason for poor growth, it is one of the main reasons.

Let’s turn to the government debt position. Despite the rhetoric of “reducing high debt burden”, it has actually increased over the last few years. In absolute terms, the total government debt has increased by 39% from Rs. 7,391 billion at the end of 2014 to Rs. 10,269 billion by September, 2017.

According to Central Bank data, debt to GDP, which was 71% at the end of 2014, has increased to 79% by the end of 2016. It would have gone well past 80% in 2017. Rather than the increase in debt, the issue is the poor economic growth which makes the debt burden more ominous (refer Fig II).

In a nutshell, the current economic strategy does not seem to be working.

A better economic strategy would be to take immediate steps to revive the economy and make higher growth the number one priority. The objective would be to push economic growth towards 5-6% immediately and then to 7-8% in a few years.

To achieve this objective, tax rates need to be brought down for identified, priority sectors which would drive growth. Government capital expenditure should be focused to provide the necessary environment for those identified sectors. Increase in current expenditure should be managed, keeping in mind the short election cycles.

As for budget deficit and government debt, let it be where it is. If the budget deficit is 5.2% of GDP, neither let it increase nor try to reduce it. If government debt to GDP is 82%, neither let it increase nor try to reduce it. Once the economic growth reaches 7-8% and the economy is running steadily, gradually decrease the budget deficit and the debt position in the long term. In other words, let it be a lower priority right now.

This is contradictory to the current economic policy.

I would argue that there are two key factors for strong economic policy making:

1.Ensure the right team is

setting policy

2.Prioritise

It is good to obtain the views of IMF, US Treasury etc. However, it is essential that local expertise provides the majority of the contents of economic policy; and in terms of local expertise, one shouldn’t rely too much on economists and theoreticians. Entrepreneurial thinking is essential to formulate a country strategy. We do have a handful of entrepreneurs who have done exceedingly well in global markets – competing with global players. Country strategy could be similar to business strategy; it is how successfully your country competes against other countries in the global market place. Therefore, the entrepreneurial input would make the plan more practical (albeit slightly more risky) rather than a theoretical roadmap provided by foreign lending agencies or local theoreticians.

The Budget proposals of successive governments and election manifestos of all the main political parties almost always tend to be a long wish list. These policy statements become irrelevant eventually as most of it doesn’t get implemented. It wouldn’t get implemented as resources are limited. Hence the challenge for the next president and government (as the current leadership is well into the second half of its term), is to come up with a more rational plan. For example, identify the five key sectors they plan to develop; what tax concessions and capital expenditure would be provided to make it happen? Quantify the outcome expected in five years. Similarly, clearly indicate the priority is to get GDP growth to 7-8% and not to reduce the fiscal deficit to 4% or government debt to 60% of GDP. Everything cannot be achieved immediately. Prioritise what should be achieved first and what should be achieved later.

The key aspect of the proposed strategy is to provide tax reliefs with a view to promoting investments.

This is not in reference to granting sweeping long term concessions for foreign sovereign investors who are eyeing the strategic national assets, but for local entrepreneurs – small and large and also foreign investors who could add long term value to the country. The concessions should be directed at the sectors which the country wants to grow rapidly over the next decade – e.g.: Logistics, Tourism, IT, KPO/BPO etc.

Sri Lankan economy is over dominated by consumption (close to 80%), which should actually shift towards export oriented investments. Therefore, the increase in VAT itself is not undesirable. However, the rate of increase (from 11% to 15%) was probably too drastic. Instead a more market based pricing mechanism for fuel and electricity could be implemented.

Providing tax concessions and lower interest rates for identified sectors, and weaker Rupee is accommodative for export related sectors, although the government capital expenditure also needs to be focused along these lines. For instance, the Government could assist in terms of providing global markets for SMEs, aggressively invest in universities and training institutes to ensure the labour is amply supplied for the identified high growth sectors etc. It is with this level of focus that one could expect FDIs to flow into these identified sectors. The absence of such measures could be the main cause for poor FDIs.

The sharp rise in the government sector salary bill by 27% in 2015 (in comparison to GDP growth of 4.8% and inflation of 3.8% in 2015) spiked government current expenditure. The government sector salary bill has already increased by 27% in the preceding two years (from 2012 to 2014). With the short election cycles in Sri Lanka, these kinds of irrational measures are not surprising. However, attempts should be made to maintain the increases of current expenditure in line with GDP growth and inflation to ensure the budget deficit doesn’t expand significantly. It is not practical to slash current expenditure sharply as proposed by certain economists.

The tax concessions introduced to selected sectors to boost growth could affect government tax revenue in the short term. However, as the economy picks up over time, despite the lower tax rates, due to higher volumes, the Government could earn higher tax revenue. The public investments to boost the growth sectors would expand the capital expenditure, although through prioritising some savings could be expected. The current expenditure should be allowed to increase at modest speed.

The above strategy may result in a marginal expansion in budget deficit (towards 6% of GDP) in the near term although it could revert to the current level of 5.2% of GDP once the economic growth picks up towards 6% in a couple of years. The budget deficit could remain around 5.2% in the medium term (say

5-10 years). Attempts to reduce the budget deficit further could be undertaken once economic growth is sustainable at 7-8% and the economy is capable of weathering a fiscal policy tightening.

Consider the business model of banks. At any given time there is a heavy debt burden on its head. Even if a minority of depositors attempt to withdraw their funds on a certain day (the money in savings and current accounts can be withdrawn on any day) even the biggest of banks could be insolvent – or wouldn’t be able to repay the depositors. Do the banks maintain their funds in a locker fearing that all depositors would turn up at their doorstep one day? The business model wouldn’t work that way as funds in the locker wouldn’t grow. It needs to be invested to make it grow and ensure the viability of the banking sector business model.

The main focus of the banks is to grow steadily while keeping the risks managed and not on how the depositors (or debt) will be repaid and reduced. If a bank is well managed, instead of withdrawing, depositors, lenders and investors would invest more in the bank.

The same would apply for a country managing its debt. If the country’s economy is growing steadily in a sustainable manner, if the policies are rational and the leaders are capable of implementation, the investors and lenders would flow in. The smart money/investors are often capable of picking sound investments. There would not be a need for IMF bail outs, entailed with the check list driven technical conditions.

This is by no means to compare a country to a bank nor is it meant to recommend irresponsible borrowing. It is just to highlight the fact that borrowing is a part of modern day business strategy and country strategy.

Strong sustainable economic growth would lead to less dependency on borrowings in the long run. The sectors on which tax concessions were granted and capital expenditure were incurred, should provide financial dividends over time. It should also be remembered that most large scale infrastructure projects would have relatively long gestation periods and just because it is not self-sustained in a year or two it doesn’t mean the investment was a waste.

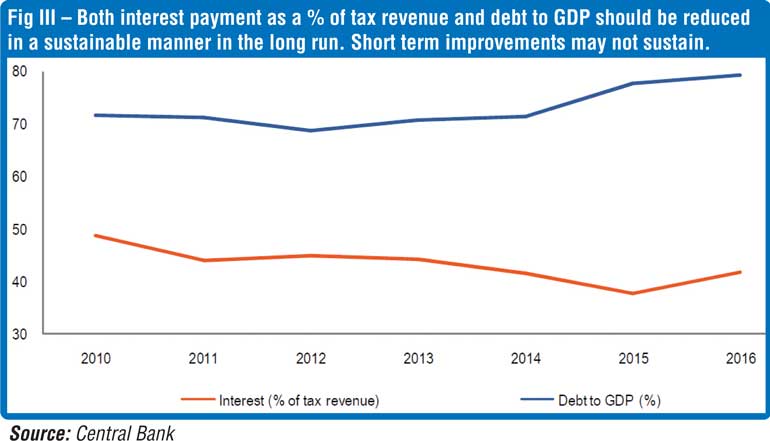

The key aspect is to monitor whether interest payment as a percentage of tax revenue could be reduced to a manageable, sustainable level in the long run along with debt to GDP (refer Fig III). High tax revenue immediately subsequent to an increase in taxes may not be sustainable as the economic growth slows, tax revenue would also slow down.

Therefore, it would be sufficient to just maintain the current level of debt in the medium term (debt to GDP of around 82%). Steps to reduce it could be undertaken in the longer term when the economy is growing steadily around 7 – 8%.

Currently we seem to be in a vicious cycle. The Government is on a quest to boost revenue through higher taxes with a view to reducing budget deficit and thereby alleviate the increasing pressure on debt. However, the higher taxes have stifled growth. Poor growth has resulted in increasing debt to GDP.

Poor growth would also affect tax revenues in due course which may push the Government to introduce more tax increases and the cycle could go on.

What is proposed is to break this cycle by prudent fiscal loosening which could revive growth. Despite a short term expansionary impact on budget deficit, economic growth would pick up and alleviate pressure on debt to GDP. Once the economy picks up, tax revenue would also increase, ensuring the debt is maintained at current levels. Once the economy is robust, steps could be taken to reduce budget deficit and debt. Hope sanity will prevail.

The writer operates a boutique,

independent macro/equity research house and can be contacted on

[email protected]