Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 31 August 2021 01:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Reflecting the global economic setback caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Sri Lanka’s worker remittances are on a declining trend since the beginning of this year. The domestic economic uncertainties, particularly with regard to foreign exchange market distortions, also seem to have contributed to the fall in inward remittances.

Reflecting the global economic setback caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Sri Lanka’s worker remittances are on a declining trend since the beginning of this year. The domestic economic uncertainties, particularly with regard to foreign exchange market distortions, also seem to have contributed to the fall in inward remittances.

Worker remittances contribute one fourth of the country’s foreign exchange earnings, and they account for nearly 10% of GDP. Hence, the decline in worker remittances will exert immense pressures on the foreign exchange market, which is already hit by export stagnation, breakdown of the tourist industry and heavy foreign debt settlements. The remittance shortfall is likely to further weaken the rupee, given the scarcity of dollars in the market in the backdrop of historically low level of international reserves fallen to $ 2.8 billion by now.

Worker remittances down

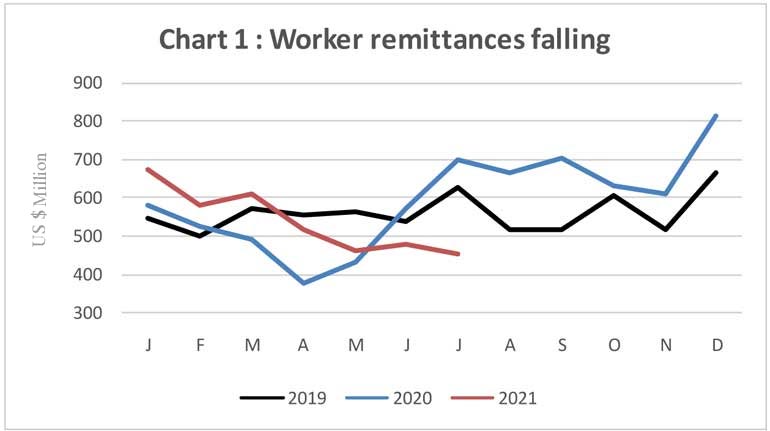

Worker remittances recorded a marginal increase of 2.6% in the first half of this year, compared with last year. This was due to the lower base in 2020. The monthly inflow of remittances is down from a peak level of $ 813 million in December 2020 to $ 453 million in last June (Chart 1).

The downward trend of remittances is rather alarming, since they have served as the lifeline in dealing with the balance of payments difficulties experienced during the past several decades. The average annual inflow of worker remittances amounted to $ 7 billion during the period 2016-2020, and it was sufficient to finance around 35% of the country’s import payments. This implies that the external payments deficit would have been much larger, if not for the inward remittances.

Exchange rate disparities among banks create uncertainty

The rupee has been under severe stress in recent months with a rapid decline in the country’s foreign reserves, as explained in my recent article appeared in Daily FT (https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Rupee-under-stress-as-trade-deficit-expands/14-721803).

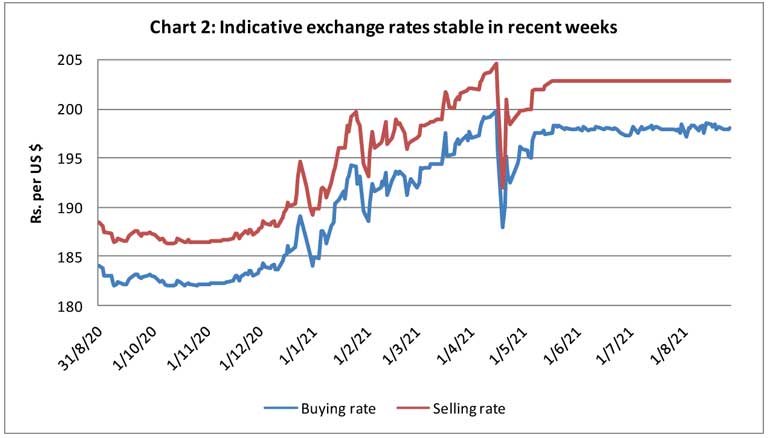

Recently, the Central Bank has declared that the exchange rate will be maintained around Rs. 200 per dollar with a “gentlemen’s agreement” with commercial banks. This type of understanding is known as “moral suasion”, which means persuasion of commercial banks to be in agreement with the Central Bank’s decision. The Central Bank’s attempt to keep the exchange rate at Rs. 180 per dollar a few months ago was not successful, as it did not have sufficient foreign reserves to defend the rupee.

The buying and selling rates of the US dollar remain at Rs. 198 and Rs. 202, respectively, according to the indicative exchange rates published by the Central Bank based on the average currency rates quoted by commercial banks for Telegraph Transfers (Chart 2).

In contrast, last Friday, some private commercial banks were buying dollars from exporters at Rs. 215, and selling to importers at Rs. 222, as published in their websites. This has been the case during the past several weeks. The State-owned banks, however, maintain their rates within the indicative rate corridor published by the Central Bank, though it is unknown whether they adhere to such rule in practice.

Such wide exchange rate disparities among banks create severe market distortions, causing immense uncertainties among market participants. This may have motivated migrant workers to use informal channels to remit part of their money to Sri Lanka, instead of relying on banks.

Black market offers attractive rates

Higher dollar rates offered in the informal market vis-à-vis the formal market seem to have been a significant factor that led to a decline in the worker remittances recorded in the balance of payments. The US dollar is said to sell in the black market at exorbitant rates of around Rs. 260 per dollar. Back market is a typical characteristic of a controlled economic environment.

Informal channels have been a popular means to transfer money across countries for many decades due to their lower costs and convenience, as against formal channels. The lower dollar rates offered by banks aligning with the Central Bank’s fixed exchange rate policy in recent times have been a major push factor for migrant workers to use channels such as Hawala – an informal fund transfer system in which money is transferred through a network of brokers (known as Hawaladars) without physical movement of cash across borders.

Economic reforms postponed

As inward remittance inflow has significantly contributed to mitigate Sri Lanka’s balance of payments difficulties over the last four decades, it has provided prolonged breathing space for the successive Governments to postpone the essential policy adjustments needed to facilitate export-led growth.

In particular, no significant attempt has been made to transform the export sector from low-technology and low-value added industries such as apparel manufacturing into high-technology industries applying modern technological knowledge inputs that require high research and development (R&D) investments.

In contrast, South Korea, which was an under-developed nation a few decades ago, soon became a high-income country by evolving export strategies to produce state-of-the-art consumer electronics and modern IT. High-tech exports are products with high R&D intensity such as computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments and electrical machinery.

Dutch disease

Dutch disease

Another disadvantage created by worker remittances has been its influence on the country’s exchange rate management. The remittances cushioned the balance of payments deficits to a great extent over the decades, and therefore, such inflows have prevented the depreciation of the rupee that would have been required otherwise to maintain export competitiveness.

This phenomenon is known as the “Dutch disease,” which refers to the adverse implications of substantial increases in a country’s foreign exchange earnings due to factors such as discovery of oil reserves. In the 1960s, the discovery of large natural gas deposits in the North Sea led to a rapid increase in wealth of the Netherlands. As a result, the Dutch guilder became stronger, eroding export competitiveness.

Similarly, in the case of Sri Lanka, inward remittances have helped to maintain the rupee at an overvalued exchange rate over the years causing anti-export bias.

Policy perspectives

The economic setback amidst the COVID-19 pandemic reflects the formidable challenges faced by Sri Lanka in dealing with such an unprecedented external shock, as in the case of the rest of the world. Given the continuation of the pandemic, the economy will continue to be adversely affected by low levels of both worker remittances and tourist earnings for a longer time. The external payment imbalance has been exacerbated by accumulated foreign debt to be settled in the near future.

The distortions in the foreign exchange market manifested by the fixed exchange rate system adopted by the Central Bank have intensified the transfer of remittances through informal channels, thereby causing a significant loss of foreign exchange to the country.

While implementing the short-run policy adjustments pertaining to the foreign exchange market to attract worker remittances, overdependence on remittances needs to be phased out in the medium-term by adopting robust policy strategies targeting export-led growth.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable at [email protected])