Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 9 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

During the last nine months of the present year (January-September 2018), the rupee depreciation had been nearly 10%, and that is what has prompted the Government and the Central Bank to take some measures (at the last moment). The situation has also sparked a heated debate on the pros and cons of liberalisation and Government’s economic policies. To underscore the gravity of the situation, the rupee depreciation during the same period last year did not exceed 5%.

The value of the rupee, which amounts to the exchange rate, not only affects the country’s or the people’s economic conditions, but also economic and business confidence. A country’s currency, in this case the rupee, is also the pride of the people. Its fall may be an insignificant event to some economic theorists, but not to the people. There can be panicky conditions, if the situation is not ameliorated properly, with immediate measures as well as long-term wise policies.

Appreciation of the dollar

The rupee has been depreciating throughout years since independence and it was perhaps unavoidable to an extent given Sri Lanka’s weaker or vulnerable position compared to other countries and currencies, particularly of the West and now countries like India and China. At independence in 1948, a dollar could be bought at Rs. 3.32 and it was relatively stable for 30 years. Now it is around Rs. 170 and still depreciating.

The general trend however has been a reflection of Sri Lanka’s low pace of development due to both unavoidable conditions (civil war, intermittent natural disasters, intense international competition etc.) and avoidable factors (excessive political expenditure, corruption, mismanagement, low enterprising culture etc.).

The central question therefore is whether Sri Lanka ever had a proper economic policy/plans (except ‘Chinthana’ and visions) to develop the country including to manage the rupee or the external sector of the economy, preferably on a bipartisan basis as much as possible. Conflictual policies on ‘liberalisation and protectionism’ between different governments have rendered more harm than good.

Primarily as a result of the US President’s protectionist policies, the dollar value has been appreciating against, for example the gold prize, during the last 1½ years. This was almost 12%. However, this has reversed slightly since April (‘Gold climb higher as US dollar eases,’ CNBC, 5 September) and the new trends are yet to be seen.

Internal reasons?

As the rupee’s sharp down turn has come exactly after this ease period (April-September), it is questionable whether the reasons are solely external. On 9 April, the dollar was Rs. 154.95, but on 4 October it rose to 170.06. As we are in largely a liberalised ‘free market,’ speculation must have played a role. It was reported that the export earners were holding their dollars without releasing them during this period given the downturn, although exact figures are not available. This has rendered the rupee to slide further during the last six months.

Another factor has been the capital outflows from the bond market, treasury bills and other financial markets. During this year there had been nearly $ 1 billion outflows, with very little new inflows. No measures were taken to boost the investor confidence. The outflow has been a pressure on the reserves and the rupee. The reason could not only be the low economic growth, hence low confidence in the economy, but also the political instability.

Although the Indian rupee has faced a similar depreciation, the repercussions could be less, given the country’s strong economy with a growth rate around 7% and political stability. The growth rate in Sri Lanka in 2017 was all time low at 3.1%. It was 4.5% in 2016. Although the Government predicted 5% growth for this year, the IMF or other agencies have not been that optimistic, predicting below 4%, probably settling to around 3.5.

Trade deficit

The most pertinent to the rupee depreciation has been the country’s deteriorating trade deficit, without proactive action on the part of the Government. A comparative picture for the six months of 2018 with that of 2017, based on the available Central Bank data, can be seen in table 2.

It is very clear that although the exports increased by 6.2% during this two years, the import bill increased two times of that value or by 12.7%. In actual terms, there was a trade deficit of $ 4.7 billion in 2017 and billion 5.7 this year during the first six months. It is true that the worker’s remittances and earnings from tourism could cover a major part of the deficit, however a more balance external trade policy could have saved those incomes for better development purposes.

It should be noted that it was the workers, working abroad, who gave Sri Lanka around $ 7 to 8 billion every year to combat the increasing import bills including super luxury cars, duty free for certain sections.

Removal of para tariffs?

There is no question that Sri Lanka’s tariffs are high compared to similar countries (Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand etc.), particularly in the case of imports. Still the average rate is around 22%. This is quite low compared to what the US has imposed on other countries recently. There are certain imported investment items even with 0% tariffs and the highest for luxury items does not exceed 37%. As we all know, super luxury cars were even given completely duty free to certain categories of people, as if the government policy is to promote other countries’ exports to Sri Lanka.

It is true that para-tariffs in the form of PAL (Ports and Airports Development Levy), CESS, VAT and NBT (Nation Building Tax) are cumbersome and complicates and discourages trade and those should have been simplified and regularised. However, the import taxes are necessary for a country like Sri Lanka to protect the local industries and agriculture while promoting exports. Leading up to the last budget, the government had started a process of removing and exempting these para-tariffs and it is still not clear how far these ‘liberalisation’ has caused the present rupee’s predicament, in addition to the appreciation of the US dollar.

Ironically, in quite a panicky reaction on the part of the Ministry of Finance, during August and September, there have been nearly 20 notifications issued to the customs and others, regarding the re-imposition of some of these para-tariffs again, including for sanitary pads and tampons. It is not clear where the government’s economic and trade policies are heading today.

Disregard for local business opinion

There have been several business leaders expressing their views against the Government’s unmanaged and unmitigated liberalisation policies, right or wrong. However, those should have been listened to and at least a dialogue should have been initiated. When DSI Group Managing Director Kulatunga Rajapaksa was expressing concerns about the removal of para-tariffs for over 250 items (Sunday Observer, 10 December 2017) he was not only talking about the footwear industry, but also others. He asked why tariffs are removed for ‘salt, yoghurt and butter’ for example.

He also questioned the rationale of granting approval for an Indian company (VKS) to produce footwear in Sri Lanka by importing all raw material while jeopardising the local small and medium scale enterprises that employee over 300,000 people. The FDI expected is only $ 250,000 in his argument. Now we have a rail investor from Germany asking duty free helicopters, ships, luxury vehicles, subsidised electricity and 4,000 acres of land for a mere 488 euro investment! (economynext, 6 October).

Similar views were expressed by Planters’ Association Chairman Sunil Poholiyadde and many others. It may be possible that some local industrialists and planters are asking too much protection not suitable for competitive market conditions. The local natural rubber producers are obviously catering to low value-added local industries and for natural rubber exports, while the high value added industries in the BOI sector are importing natural rubber ($ 288 million) from other countries.

From purely a theoretical point of view one can argue that it is the way the markets operate. However, here we are talking about human beings and their livelihoods, and therefore there should be a possibility of bridging the mismatch between natural rubber production in the country and the emerging value-added rubber product industries for exports.

This is why we have democracy and elected governments and responsible state officials with necessary research backing. There is no much point in exporting natural rubber overseas. While the already formulated ‘Sri Lanka Rubber Industry Master Plan (2017-2026)’ should be acclaimed, the bridging the above gap should take a major policy priority. This is only an example.

Conclusion

Obviously, there are other factors that have affected the rupee depreciation. Increasing budget deficits, primarily because of high defence and political expenditure, and associated foreign borrowings, in addition to meeting the trade deficits, have triggered and aggravated the situation. All have not been discussed here. While the foreign borrowings remained at a high level by 2015, since then over $ 20 billion have been borrowed to pay interests, pay back debt and offset foreign exchange deficits. That is why and how around $ 9 billion reserves are kept.

Therefore, the Central Bank (or the Government) is in a dilemma whether to release the reserves to save the rupee, or keep primarily aloof, allowing the rupee to fall further hoping it might naturally promote exports and discourage imports. The fiscal (tax) measures so far taken by the Ministry of Finance are only minimal. There is this liberal economic theory that a more ‘natural price’ for the rupee (meaning much more devalued rupee) is the best for free trade. These theorists too much believe in the nature of markets, while markets are manipulated by ‘others’ for different purposes and interests. This is in a context where the IMF has warned that the world must be at the brink of another financial meltdown or even a great economic depression.

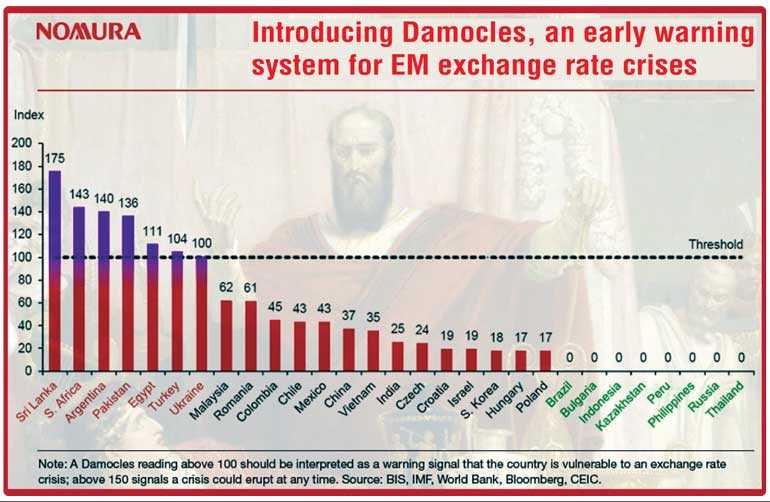

Sri Lanka would be lucky if it can escape the NOMURA warning that the country is not only in a critical situation, like South Africa, Argentina, Pakistan, Egypt, etc., but at a stage where a ‘crisis could erupt at any time.’ This can be an exaggeration, but what the situation highlights is the lack of responsible handling of the country’s economy with a balanced economic policy.

While it is true that Sri Lanka should promote exports to the maximum and open up as much as possible, that should not be done at the expense of local industries and agriculture; and the people and their livelihood, to suit a theory or satisfy certain sections of the international community. Sri Lanka is not a robot-land suddenly converted into a mere component in the global supply chain, but an ancient country with nearly 22 million people, with traditions, lifestyles and livelihood patterns.