Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 14 September 2021 01:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is widely recognised that a country’s central bank should have the independence to conduct monetary policy, free of political influences, solely targeting its core objective – economic stability, more specifically price stability. Accordingly, central bank independence (CBI) has become a key prerequisite of monetary policymaking across the world over the last three decades.

The inability of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) to enforce a coherent monetary policy framework independent of political pressures since last year has led to the present economic volatility, as I discussed in the last week’s FT column (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Avoiding-IMF-prolongs-SL-s-macroeconomic-instability/4-722718).

Heads rolled

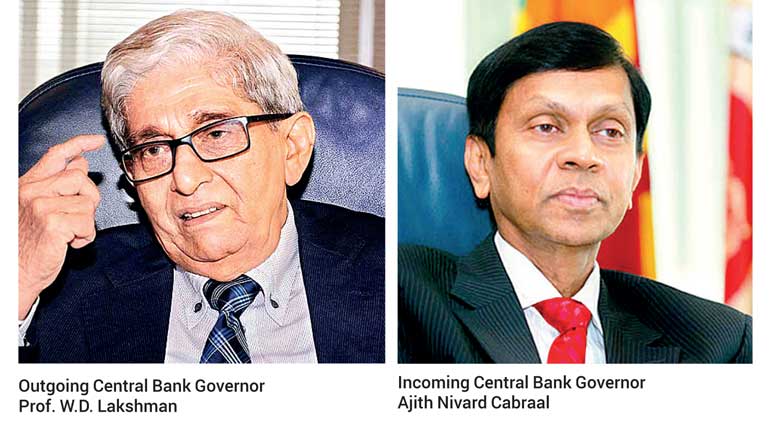

In the backdrop of the economic catastrophe, heads are rolling in the Central Bank. The outgoing Governor Prof. W.D. Lakshman is leaving behind an economy ravaged by imprudent monetary policy built on a flawed Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

While rejecting mainstream economics, he embraced MMT to meet the Government’s cash requirements by expanding the money supply. This reflects the CBSL’s failure to shield itself from the political authority which demanded money creation to offset its revenue shortfalls. Eventually, the Central Bank’s core objective – price stability – is foregone.

It is questionable how far the CBSL could be distanced from political pressures in the coming months, as a State minister is tipped to be appointed as its Governor this week with unprecedented Cabinet ministerial powers and privileges.

Economic imbalances

The economy is facing severe internal and external imbalances. Internally, inflation is picking up due to excessive money growth, exchange rate depreciation, and supply-side constraints. Externally, the balance of payments deficit exacerbated by heavy foreign debt commitments has led to the depletion of foreign reserves and rapid rupee depreciation over the past couple of weeks. The root cause of these imbalances is the high budget deficit of over 12% of GDP, as I reiterated in this column many a time.

Since last year, the CBSL has been too lenient to accommodate the Government’s cash needs by purchasing Treasury bills and bonds in the primary market that led to an excessive increase in currency issues, commonly known as money printing. The increase in market liquidity caused by exorbitant growth in the overall money supply has exerted pressures on inflation, the balance of payments, foreign reserves, and the exchange rate.

Neglecting the repeated requests made by the CBSL to keep the exchange rate around Rs. 198-202 per dollar, commercial banks bought and sold dollars at much higher rates. Black markets rates are even higher.

As a further step to overcoming the foreign exchange crisis, the CBSL imposed exchange restrictions on over 600 imported items last week to prevent depletion of foreign reserves and depreciation of the rupee. This has further aggravated market uncertainties.

Different views on independent central banking

The relationship between the central bank and the government varies from country to country. There is consensus that a country’s central bank should be completely independent of the government, as political pressures could hurt its ability to conduct sound monetary management aiming at price stability, which has surfaced as the core responsibility of the monetary authority nowadays.

The alternative view is that the central bank should be under the direct control of the government since the bank should respond to the will of the people in a democratic society. In practice, however, central banks operate between these two extreme paradigms and enjoy different degrees of independence in each country.

Central bank independence

Unquestionably, CBI is essential to achieve price stability, which is the sole objective of modern central banks. The main argument in favour of central bank independence concerns inconsistency over time. As regards monetary policy, the time inconsistency problem arises when politicians attempt to manipulate the trade-off between employment vis-à-vis inflation.

In order to retain popularity ahead of an election, the governments with a short-term focus are tempted to reduce interest rates and to raise the money supply so as to induce employment. This helps to boost employment and incomes in the short run delivering the anticipated electoral gains to politicians, but it causes inflation in the long run. Therefore, it is recognised that a central bank needs to be independent of political pressures to conduct monetary policy with a long-term horizon.

Monetary Board appointments

Central bank independence can vary across countries depending on the legal provisions of (a) terms and conditions on appointment and dismissal of the governor and the monetary board, (b) government’s involvement in policy decisions of the central bank, (c) importance given to the price stability objective, and (d) limits on government borrowings from the central bank.

In terms of the Monetary Law Act, the Monetary Board is responsible for powers, duties, functions, and management of CBSL. At present, the Board has five members consisting of the Governor as the Chairman, Secretary to the Ministry of Finance, and three appointed members. The Governor and the other members except the Finance Secretary are appointed by the President.

Recognising the undue political influence that may cause on monetary policy through such appointments, an attempt was made to change the appointment process in terms of the Central Bank Bill which was drafted three years ago with the blessings of the then Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera, sadly who is no more with us. The Bill was scrapped by the present Government, leaving no hope for CBI.

Fiscal dominance

The monetary policy space is severely restricted by the CBSL’s failure since last year to resist financing the unbridged budget deficit. As there have been difficulties in raising funds from domestic and foreign capital markets to finance the deficit, the CBSL has used its monopoly power to create ‘fiat money’, to lend to the Government along the lines of MMT.

The revenue generation by the Government through such money creation, known as ‘seigniorage’, has increased the CBSL’s monetary base which brought about a multiple expansion of the aggregate money supply causing demand-pull inflation, as discussed in the previous columns in this series.

Central bank independence becomes crucial for insulating monetary management from such inflation-biased political pressures. It is broadly recognised that the more independent central banks perform better in achieving their main objective – price stability.

Twin deficits

The limitations faced by the CBSL in conducting independent monetary policy are deeply rooted in the twin deficits – fiscal deficit and current account deficit of the balance of payments. In Sri Lanka, the twin deficits will continue to remain high with mounting debt commitments in the coming years, as per official projections.

The persistent fiscal deficits restrain interest rate flexibility while continuous deficits in the balance of payments restrict exchange rate flexibility. In the absence of the flexibility of these two price instruments, an open economy cannot reach equilibrium, as demonstrated in the famous Mundell-Fleming model in monetary theory. Sri Lanka’s current economic turmoil amply proves this theory.

Impossible Trinity at work

The ‘Impossibility Trinity’ theorem derived from the above model suggests that a central bank can choose only two out of the three policy options – stable exchange rate, free capital flows, and independent monetary policy, as I elaborated in a previous FT column (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Policy-trilemma-poses-formidable-challenges-to-interest-and-exchange-rate-management%20/4-713226).

Based on this premise, I argued that the CBSL will not be able to keep low interest rates and an arbitrarily fixed overvalued exchange rate while entertaining free capital flows. This is proved to be correct as evident from the recent volatility in the domestic money and foreign exchange markets in the country.

Corrective measures unlikely

It would be a daunting task to rescue the ailing economy from the present crisis. The budget deficit needs to be brought down to around 5% of GDP from 12%, which is impossible given the tax cuts and spending spree. The exchange rate should be allowed to find its equilibrium in the free market, which would ultimately lead to rapid rupee depreciation. This is unavoidable, as long as the CBSL does not have sufficient foreign reserves to support the overvalued exchange rate.

The authorities could have averted such painful remedial measures, had they adopted the right policies at the right time following the mainstream economic principles which have been proved to be right across the world. Experimenting with alternative models since last year has caused economic havoc putting the ordinary man to severe hardships with consumer good shortages, long queues, and high prices.

Central bank independence, which is vital to overcome the current economic imbalances, seems to be a remote possibility, given the current circumstances.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable at [email protected])