Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 18 May 2020 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The destructive COVID-19 pandemic

The unanticipated external shock delivered to Sri Lanka’s economy in the form of destructive COVID-19 pandemic has been costly in many terms. It put Sri Lanka’s economy many decades backward forcing it  to restart from the beginning again. This happened after it began to show the first signs of slow economic recovery from the disastrous fallout of Easter bombings of 2019.

to restart from the beginning again. This happened after it began to show the first signs of slow economic recovery from the disastrous fallout of Easter bombings of 2019.

COVID-19 disrupted the normal supply chain that had been developed for internal trade within Sri Lanka and for external trade outside Sri Lanka. That prevented the local products from reaching markets here or outside efficiently and effectively. Large corporates, hitherto considered invincible giants in industry and commerce, were brought to their knees pleading for government support for lack of markets, liquid cash and resources to sustain continuity. As for medium, small, mezza, micro and self-employed who make the largest sub-component of the economy, it was fatal beyond redemption.

A flattened-out U shaped recovery

By all accounts, all Sri Lankans have been made poorer needing external support for surviving, sustaining and prospering. Since modern science has so far not come up with an effective anti-virus vaccination, all we can expect is that COVID-19 could be brought under control but not totally eradicated. Hence, the economic recovery from the pandemic cannot be rapid, known as V shaped, but prolonged, taking the shape of a flattened-out U, causing innumerable hardships to people and the economy in the interim before it would recover to original levels. This is frightening but something undesired to be reckoned with.

Relying on visible hand of armed forces and the bureaucracy

To come out of the catastrophe, the recommendation has been not to depend on the invisible hand of the private initiatives, but the visible hand of the armed forces and the bureaucracy. Even the special report on A New Economic Vision prepared by the team of economists headed by former Governor Indrajit Coomaraswamy and made-up of mainstream free-market economists for the liberal thinking Pathfinder Foundation had recommended that the government should take leadership in controlling COVID-19 but it should do so without stifling the private sector as the primary engine of growth and wealth creation. It had also highlighted that policy action should be ‘pragmatic and free from ideological bias’.

Cabraal: The pragmatic and ideology-free policy maker

Ajith Nivard Cabraal, another ex-Governor of the Central Bank, in a series of policy recommendations, had emphasised on the need for a strong government to tackle a massive human and economic disaster like the COVID-19. Cabraal is known for his pragmatic and non-ideological approach to economic issues. In 2009 when IMF was sitting on his request for a standby arrangement at the instance of the then US government, Cabraal did not criticise IMF as an institution propagating neoliberal economic ideas, then known as the Washington Consensus.

Here, he was prompted by two considerations. One was that by 2000, the Washington Consensus had already died and he did not want to relish on skinning a dead animal. The other was that by that time economic policies of IMF had evolved from beyond the narrow Washington Consensus taking into account emerging global developments. Hence, the pragmatic and non-ideological man in him caused him to restrain himself from uttering any slogan that might go against the government’s move for seeking IMF assistance at that time.

Limited fiscal space for the government

The Coomaraswamy report had justified the government’s visible hand in tackling COVID-19 pandemic issues because the government needed to work ‘big’ to act effectively to bring a massive disaster of that proportion under control. But it had highlighted that the government’s capacity to do so has been  constrained by lack of space due to restricted budgetary environment it had been facing. Hence, the government had relied on central bank’s unelected power to print money to provide immediate relief to the economy.

constrained by lack of space due to restricted budgetary environment it had been facing. Hence, the government had relied on central bank’s unelected power to print money to provide immediate relief to the economy.

But as I had argued in my previous article in this series (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Use-of-Central-Bank-s-unelected-taxation-power-to-fill-it-will-bring-cheers-today-tears-tomorrow/4-699956), it would bring about a worse outcome in the form of inflationary depression making central bank action totally ineffective. Hence, it is in the interest of the economy for the government to take full control of the situation and relieve the central bank of this undesired social responsibility.

B.R. Shenoy: It is real sacrifices and not imaginary sacrifices that matter

Indian economist B.R. Shenoy who taught economics to many of the leading economists of 1940s in the University of Ceylon has provided rationale for not using central bank printed money for long-term economic prosperity. In a book published in 2004 under the title ‘Theoretical Vision’, he has made a distinction between voluntary savings and involuntary savings.

Voluntary savings are real sacrifices made by people by curtailing real consumption and made available for investors for use in real investments. For instance, if a man produces 100 kg of rice and consumes only 80 kg, he makes a voluntary saving of 20 kg of rice in real terms. This is made available to investors to produce, according to Shenoy, higher order goods which economists call investment goods.

These investment goods will produce more consumption goods in the future, increasing the real income of people thus facilitating them to consume more consumption goods. It therefore leads to a change in the economic structure and thereby generation of long-term economic prosperity.

Involuntary savings don’t work in the long-run

Involuntary savings are those savings created out of the artificial credit and deposit creation by banks with the support of money printed by the central bank. These savings are imaginary savings arising from imaginary assets of financial institutions as against the real savings made by people by curtailing real consumption. Shenoy says that at first such imaginary involuntary savings can increase output but cannot sustain it since they are not backed by real production of investment goods.

Hence, it leads to disaster. As such, relying on central bank’s unelected power to finance COVID-19 rescue package in the immediate term is justified. But to rely on it continuously will bring disaster to an economy since it leads, as I have argued in the present case, to the generation of inflationary depression. This will force a central bank to sacrifice all its hard-earned gains.

Avoid inflationary depression

In this scenario, coming out of COVID-19 economic fallout needs real resources and it is only the government that can supply such real resources by taxing people. The US based Columbia University history don, Adam Tooze, in a recent article in Foreign Policy (available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/13/european-central-bank-myth-monetary-policy-german-court-ruling/) has argued that COVID-19 pandemic has dragged central banks away from their safe havens of monetary policy and planted them as activist partners of economic policy orchestrated by politicians.

Though this has been the global normalcy today, it has a limit. The imaginary involuntary savings they make cannot sustain economic prosperity in the long-run and prevent the consequential inflationary depression within the economy. Hence, central banks should hand over the baton of leading the economy to the visible hand of the government. It can be a facilitating supporter but not the leading proponent of post-COVID-19 economic reconstruction.

But for the government to take over the job, it should have adequate fiscal space meaning that it should have an adequate resource base to help out affected people to sustain as well as businesses to re-establish themselves. This is what the Sri Lanka government is lacking today.

A handicapped government

As I have presented in my article referred to above, Sri Lanka’s government has been handicapped not only by an emerging constitutional crisis but also by the distortions it had introduced to the tax collection system. The government had introduced a series of generous income tax and Value Added Tax or VAT reforms at the beginning of the year in fulfilment of one of its presidential election promises. Though the objective of these reforms had been to catch more people into the tax net and increase the revenue yield in the long run, in the immediate time period, it has been extremely costly to its revenue collection processes.

Short to medium term costs of tax reforms

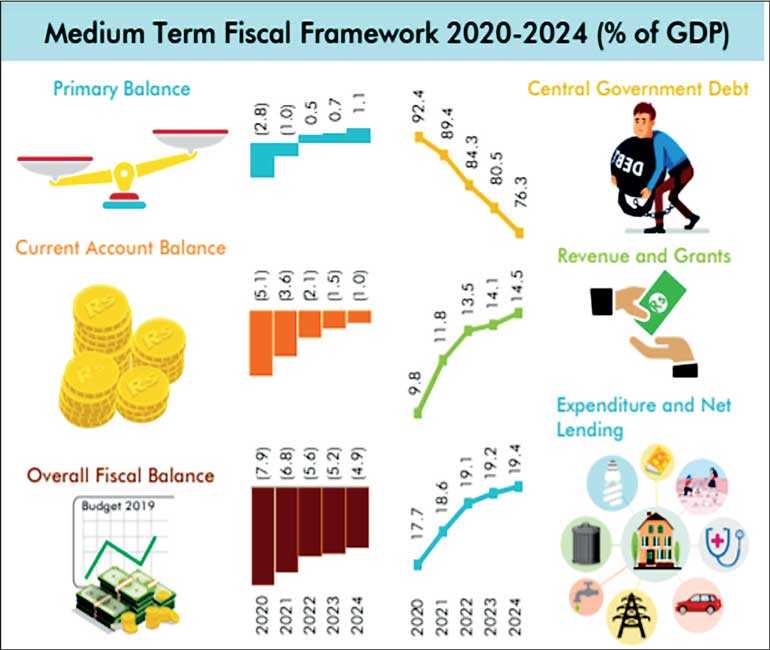

The Central Bank Annual Report for 2019 has estimated that in 2020, the total revenue of the government would be at 9.8% of GDP amounting to Rs. 1,560 billion. If the government had been  successful in maintaining the same revenue to GDP ratio of 12.6% which it had attained in 2019 in 2020 as well, the likely revenue in the latter year would have been Rs. 2006 billion. This means a loss in the revenue amounting to at least Rs. 447 billion or 2.8% of GDP. On top of this, the Central Bank’s estimate of the medium-term fiscal scenario is quite frightening as illustrated in the Infographics attached to Chapter 6 of the report. This is presented in Graph 1 of this article.

successful in maintaining the same revenue to GDP ratio of 12.6% which it had attained in 2019 in 2020 as well, the likely revenue in the latter year would have been Rs. 2006 billion. This means a loss in the revenue amounting to at least Rs. 447 billion or 2.8% of GDP. On top of this, the Central Bank’s estimate of the medium-term fiscal scenario is quite frightening as illustrated in the Infographics attached to Chapter 6 of the report. This is presented in Graph 1 of this article.

An undisciplined fiscal scenario

From the low base of 9.8% of GDP in 2020, government revenue will begin to increase slowly. In 2021, it is estimated to rise to 11.8% of GDP, still below the level of 12.8% achieved in 2019. In 2022, it would rise to 13.5% of GDP, well below the planned target of 17% of GDP made in 2018. In 2023 and 2024, the revenue targets are very modest at 14.3% and 14.5%, respectively. This has to be contrasted with the ambitious revenue target of 17.5% made for 2023 in 2018 under the old income and VAT regimes.

With these low revenue bases, all other fiscal numbers would be unwieldy. The government dissavings as reflected in the Current or Revenue Account balance would rise to a historical peak of 5.1% in 2020 and are expected to be in the negative range in the medium-term, albeit at a decreasing rate, since then. The budget deficit, according to the Bank, would rise to 7.9% of GDP in 2020 and remain at around 5% thereafter. Thus, the fiscal discipline which had been planned to be attained under the old tax regime is to be sacrificed under the new tax regime. Hence, instead of increasing the revenue yield, the estimates made by the Central Bank reveal the opposite story.

The loss of a regular cash inflow

The new tax reforms, while increasing the tax-free threshold to Rs. 3 million from previous Rs. 1.2 million, had abolished two advance tax collection systems that had been working perfectly up to date. One was the advance income tax collection made through employers from the salaries of employees known as Pay-As-You-Earn or PAYE. This was a compulsory payment done automatically enabling the Inland Revenue Department to collect about Rs. 50 billion every year at the rate of Rs. 4 billion per month.

The other was the withholding tax on interest income and other miscellaneous incomes collected at source from income recipients. That tax too generated an automatic cash inflow of Rs. 50 billion per annum or Rs. 4 billion per month. By abolishing these advance tax collecting systems, the Inland Revenue Department has lost a monthly combined cash inflow of Rs. 8 billion.

Though this was to be collected quarterly from the taxpayers concerned, an easy tax collection system that had been in place for more than a decade has been given up by the government for an expected higher income in the medium to long-run by catching more liable people into the tax net. This is where the mistake was made by the government.

APIT is more confusing

After realising its mistake, the government has tried to make amends by slightly revising the advance tax collection system. It has issued instructions to employers to get the consent of their respective employees to deduct an advance payment of income tax, code-named APIT to distinguish it from the old PAYE, and remit to Inland Revenue Department monthly. Since APIT is a voluntary payment, it cannot expect to generate the same tax yield as the yield generated under PAYE or old Withholding Tax system. Anyway, the victim is the government which will lose its monthly cash inflow.

Tax reforms should be tried out under normal situations

These types of tax reforms should be tried under normal situations. The present COVID-19 environment is not the ideal situation to do so. It has handicapped the government by restricting its freedom to respond to the rising demands made of it by affected individuals and businesses. If the revenue does not flow into the Consolidated Fund, there is no way for the Minister of Finance to withdraw funds from it by issuing a warrant under the Constitution.

Even after the expected approval of a formal budget by the new Parliament, the government will continue to suffer from this handicap due to its low revenue base. It will not be able to meet its financial obligations unless it borrows heavily from the local and foreign markets. Both would worsen the country’s debt situation pushing it further down to an inescapable debt trap. This has to be avoided at all costs.

Given these circumstances, it will be prudent for the government to postpone its generous tax reforms until the country returns to normalcy.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)