Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 3 July 2021 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Remember the first Buddhist message recorded at Mihintale, calling upon the King to remember he is only the guardian of the land which he must protect for future generations, and urging to show compassion to the animals. Yet the cost of quick development today is borne by nature, forests, rivers, animals on land and sea

By Sarala Fernando

This article looks at initiatives undertaken by Western countries like the US, Canada, Australia and France to come to terms with dark episodes in their history and their relevance for Sri Lanka.

In the US, the focus was on racial discrimination and injustice to the black community as witnessed in the flowering of the Black Lives Matter movement and the naming of Juneteenth day celebrating the end of slavery.

In France it was foreign policy and colonial experience such as their part in the genocide in Rwanda and the nuclear testing in Algeria.

In Canada, the recent discovery of a grave site containing the remains of 215 indigenous children taken away from their families for forced re-education was described by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as a “painful reminder” of a “shameful chapter of our country’s history”.

In 2008, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered a formal apology in Parliament to Indigenous Australians for forced removals of their children by Australian Government agencies.

In the case of Rwanda, where bilateral relations had been ruptured since 27 years, a panel of experts had reported in March 2021 that while France bore responsibility for not breaking with the regime sooner, there was no evidence of French complicity in the genocide.

These conclusions formed the basis of President Macron’s historic visit to Rwanda in June where he acknowledged that: “…France has a role, a history and a political responsibility in Rwanda. It has a duty: it must look history in the face and recognise the share of suffering that it inflicted itself on the Rwandan people by opting for too long to keep silent instead of examining the truth.”

Bilateral diplomatic relations have since been restored with the exchange of Ambassadors and a new development cooperation programme has been extended to Rwanda.

However, despite the progress on Rwanda, coming to terms with France’s colonial past in Algeria has been more elusive. French nuclear experiments, according to the internet, are reported to have been more deadly than those of Hiroshima causing the deaths of around 42,000 Algerians in addition to contamination and extensive damage to the environment.

France’s dilemma between the approaches on Rwanda and Algeria needs some explanation. Admitting to deliberate nuclear testing involving the deaths of local people is as unthinkable as admitting to using deadly chemical agents as the US did in Vietnam. How can an apology be issued or compensation be calculated for the admission of such culpability?

The US for example justifies the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan as being necessary to bring the World War to an end and save many lives. On the other hand, the Hiroshima museum serves as an archive to memorialise the horrors that were unleashed and to plead for the banning of such terrible weapons.

Fortunately, since that time, international agreements have been negotiated to ban nuclear weapons tests as well as chemical weapons use, resulting in the strengthening of global norms alongside a vibrant network of NGO watchdogs.

Lessons from high level apologies

What is to be learned from these Western examples of high level apologies? A common thread in this approach is that even with political leaders committed to human rights, transitional justice measures seem to take place only in situations of historical recall when those in power no longer feel any sense of actual responsibility or role in the historic events.

Some cynics suggest that that such proactive human rights initiatives are a cover for powerful nations while they typically take aggressive stands towards developing countries in UN fora. Yet recently we witnessed how international pressure can be helpful, judging by the policy shift in Sri Lanka on amending the PTA and releasing LTTE detainees.

In an unusual turn of events last week, there was welcome consensus across the benches in Parliament urging the President to release those LTTE detainees against whom there was insufficient evidence for prosecution.

While many developing countries “name and shame” their previous colonial masters, calling for reparations and return of stolen artefacts, etc., Sri Lanka has not taken this path. Is this because “repentance” and “pardon” is a Christian approach, somehow alien to Buddhist philosophy which calls instead for compassion and kind deeds? Sri Lanka’s support for Japan at the San Francisco Peace Conference, urging that it should not be called upon to pay war reparations, was perhaps based on such thinking.

In similar vein, independent commissions like the Kandyan Peasantry Commission were tasked not so much to condemn the colonial powers but rather to address domestic political pressures and compensate those whose lives were wrecked for rebelling against British colonial rule. However, academics have documented colonial atrocities like Susantha Goonatilleke’s account of the terrible crimes committed by the Portuguese in Sri Lanka, using mainly Portuguese sources.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is a country vulnerable to both man-made and natural disasters and perhaps a fatigue has set in with all the endless problems encountered. Yet, which other people could have met with such resilience, three decades of armed conflict, an unprecedented tsunami, the Easter bombings and yet managed to rebuild better?

We need to acknowledge the positives – the military’s role has been indispensable in nation-wide rehabilitation and humanitarian programmes. The security forces are the first responders in times of disaster, they have helped save lives, rebuild damaged places of worship, constructed houses, schools and, even playgrounds, roads, bridges, run health camps, provided water and sanitation and access to markets.

The Army has de-mined conflict affected areas, making them safe for residents to return and enabling Sri Lanka to reach its goal of a mine-free nation in the near future. This tangible contribution by the security forces on the ground on a daily basis far outweighs the political efforts of the distant diaspora trying to keep alive allegations from decades gone by.

Nature vs. development

Yet, many are asking why our nation is facing so many troubles of epic proportions. Some believe that we have destroyed the balance between nature and development and are now paying the price.

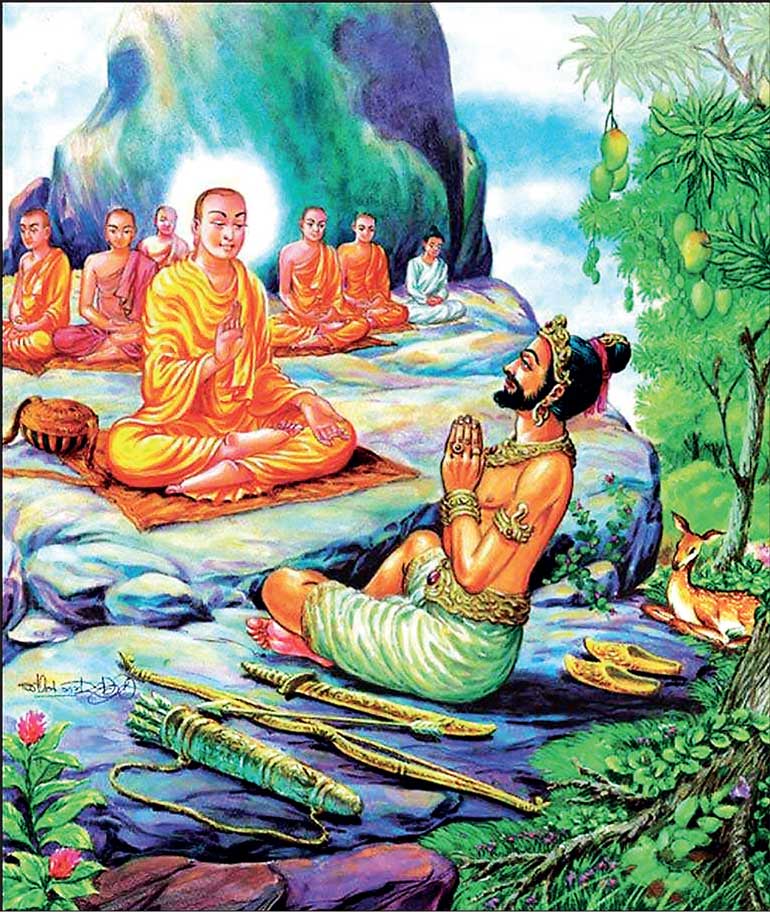

At this time of Poson, we are reminded of the first Buddhist message recorded at Mihintale, calling upon the King to remember he is only the guardian of the land which he must protect for future generations, and urging to show compassion to the animals. Yet the cost of quick development today is borne by nature, forests, rivers, animals on land and sea.

In a book for the National Trust Sri Lanka on Maritime Heritage, ancient ports and harbours, Ashley de Vos wrote of how the Sri Lankan elephants have suffered, shot and killed for trophies in their thousands by foreign hunters, trapped and chained and taken to be sold in far-off lands during the colonial period.

After independence some measures were taken by wildlife and environmental experts to enact legislation to give protection to the elephants, as well as through the creation of national parks and initiatives such as Pinnawela for the care of abandoned baby elephants. Yet all these efforts to confront the dark have been dashed by the present craze for profit and revenue, overriding the needs of the animals and their protection.

The only hope is that a younger generation, conscious of environmental protection and animal rights, is rising. It is they who exposed the theft of baby elephants from the wild to offer them for sale, even killing the mother elephants. Worse still, officers of the Wild Life Department were found to be complicit in this crime by making fraudulent entries in their elephant register.

This is why alarms bells rang recently when the main culprit of the baby elephant scandal, Ali Roshan emerged, allegedly to treat the wounded tusker in Vavuniya (who died the very next day). Questions are now being asked why he was allowed to attend to the elephant and what happened to the tusks?

Has the Wild Life Department a protocol for the disposal of the tusks of dead elephants, in keeping with the international ban on trafficking of ivory? If temples are receiving these tusks or are involved in their sale, it would be against the philosophy of the Buddha whose life story is often depicted in nature, with protective elephants in attendance.

In the ‘Maritime Heritage’ book, Anslem de Silva wrote of how the Hawksbill turtle species was driven to extinction by the ceaseless exploitation of its shell for the creation of artistic objects to wear or admire. It is now protected under law and so many young people have been involved in projects to save the eggs laid on the beach and to release the young back into the sea.

All these valuable efforts to confront the dark have been destroyed by the X-Press Pearl disaster which has resulted in hundreds of marine mammal deaths, particularly turtles, of which over 100 have been washed ashore so far.

If as the Captain of the X-Press Pearl is reported to have testified in Court that some person in power had said, “let the ship burn, we can collect the compensation,” that person should be held liable for the worst maritime catastrophe in this country, the environmental recovery from which may take a 100 years.

Some allege there is a cover-up. How else to understand why on the heels of the X-Press Pearl disaster, the Tourism Minister is boasting of millions in tourism investment, including unsolicited projects for cable cars and underwater restaurants?

Should not the focus be on how to repair the damage to the marine environment which is the platform for so many important economic activities? Can tourists return to Sri Lanka until its surrounding sea is safe and have we driven away the whales and dolphins that have delighted so many and have lived in our waters for centuries?

The writer retired from the Foreign Ministry as Additional Secretary and her last Ambassadorial appointment was as Permanent Representative to the UN and international organisations in Geneva. Her Ph.D was on India-Sri Lanka relations and she writes now on foreign policy, diplomacy and protection of heritage. She could be reached via email at [email protected]