Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 26 October 2018 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There are much deliberations at ‘high places’ by many ‘experts’ in order to find a solution to the carnage that is taking place on the rail tracks, while wild elephants succumb to gruesome deaths at an alarmingly rapid rate.

In typical Sri Lankan style, there are committees appointed to study and report on the issues – when the facts are too well-known – and then, when the report is submitted, it will gather dust on some shelf somewhere.

When there is a serious issue at hand, those of us who have been in the upper levels of private sector management know that wide consensus-based decision-making is not the best under the circumstances.

The need of the hour is to take swift decisions, the best decisions under the circumstances, and to immediately mitigate the crisis. It may not be the best solution, but to stem the rot, something needs to be done fast and effectively, and this calls for swift decisive actions, without wasting time on prolonged discussions.

The need of the hour is to take swift decisions, the best decisions under the circumstances, and to immediately mitigate the crisis. It may not be the best solution, but to stem the rot, something needs to be done fast and effectively, and this calls for swift decisive actions, without wasting time on prolonged discussions.

In the same manner, what is needed in this case is to take stock of the present situation, and come up with a simple, effective and readily implementable solution quickly.

So let’s take stock of the current situation.The deaths are occurring on certain stretches of the railway tracks predominantly. These areas are readily known to the scientific community doing research on elephants, such as the Palugaswewa and Welikande areas.

These areas cover several kilometre stretches of the track at specific places.

The deaths occur predominantly at night.

Having the engine drivers slow down when close to these areas is not a realistic option. It just won’t happen. This solution has been tried for several years, with sign boards warning drivers to slow down. But, due to indiscipline and negligence, and the usual Sri Lankan style of lack of application and follow-up, and the inability to implement a decision, it has been an utter failure.

Similarly, installing high-tech solutions, such as thermal imaging, is of no use because the drivers will not generally heed the warnings.

Having a wild life warden travel in the locomotive also has its downside, as it is not clear whether the warden will have authority over the engine driver to force him to slow down.

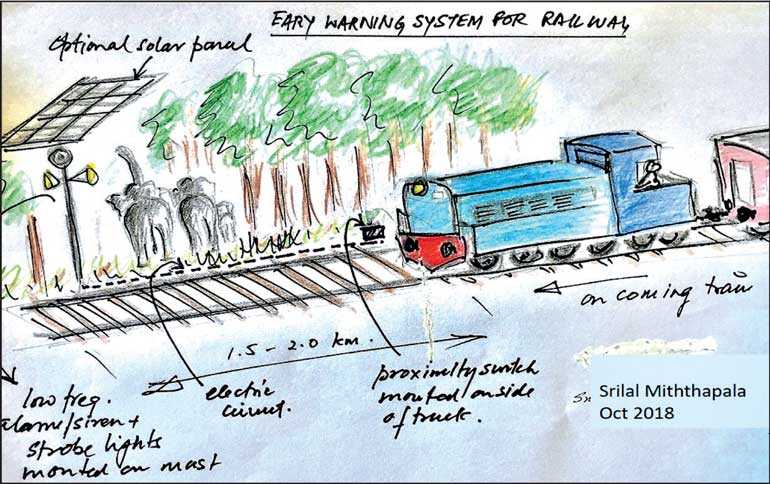

Given these constraints, the only logical short-term solution has to be an early warning system to chase away the elephants, triggered automatically by the approaching train. This will take away all the unreliable human intervention variables from the equation.So, with this in mind, I greased the rusty cog wheels of my early engineering training and came up with a simple, effective, and relatively cheap idea that may be worth considering. My in-plant training at the signals division of the railways many moons ago did help.

The early warning system is a wired electrical alarm triggered by the train engine itself. It will sound an audible and visual (strobe lights) alarm some 1.5-2 km ahead of the train to frighten off any elephants in the vicinity of the tracks.

The triggering device could be a simple proximity switch by the side of the track, or a pressure switch embedded in the track (or other similar device). The wiring circuit could be run along the track to the point ahead where the alarm is installed. The alarm itself could be a low frequency powerful horn (elephants hear low frequencies better than high frequencies) and a set of multiple strobe lights mounted on a mast.

The electrical power required for the entire system for 2 strobes (500 Watt/sec) and one powerful alarm will require about a total of 1.5-2 KW of power (according to my rusty engineering knowledge). In some areas, there will be grid electrical power available.

If off grid, a solar panel array coupled with a battery bank will have to be used. This will have to be sized so that there will be sufficient power stored for the system for one whole night or more, allowing for overcast days when charging will be less during the day.

My basic calculations indicate that each unit would cost in the range of Rs. 1.5 million and several such units will have to be installed along the length of the track. As the train passes, it will trigger different track circuits along the stretches that are known elephant crossing areas.

The system is easy to install, not hi-tech, and relatively inexpensive.

I am not for one moment suggesting that this is a fool proof method that will work. A few pilot systems have to be installed and tested out. In fact, some of the elephant experts whom I talked to say that over time, the elephants (who are very intelligent animals) will get used to the alarm and not move away – the proverbial ‘wolf, wolf’ story.

In the absence of any quick ‘doable ‘ solutions, maybe something like this needs to be tried while the longer term, more permanent solutions are debated and implemented. We owe it to ourselves to do something fast. At least to try and do something.

Of course the root cause is a much larger and complex issue: The Human-Elephant Conflict, which is the result of elephants losing their habitat and coming into contact with humans more often than before. A few weeks earlier, while on a drive to the East Coast, I saw seven elephants at the height of mid-day by the road side in the Habarana area, some soliciting food from passers-by. A decade ago, one would have seen elephants on the road only late in the night. With dwindling food sources and habitat, the elephants are now venturing out into ‘human territories’.

The solutions to the HEC are very complex, and need a holistic national effort to mitigate. Alas, that is but a pipe dream.

As Dr. Upatissa Pethiyagoda so aptly said, “We are the intruders and we deserve to honour both human rights and elephant rights. As a tourist attraction, they may have already paid for their keep, and it is time for us to reciprocate”. He went on to say that we have to put the elephant first, and that we should not call it the Human-Elephant Conflict, but call it the Elephant-Human Conflict. Until there is such a paradigm shift in our thinking, nothing can be done.

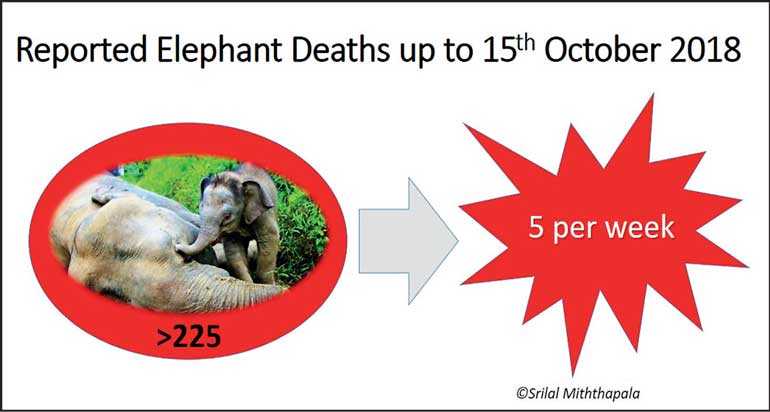

Today, elephants are dying at an alarming rate, and not only due to train accidents. It is reported that till 15 October this year, some 225 elephants have died. This translates into about five deaths per week – and that’s only the number that is recorded. What about the elephants that die inside jungles and are not accounted for?

Can we afford to sit back and watch Sri Lanka’s bountiful nature be ravaged and decimated before our eyes?

The Dhammapada says: “All beings tremble before danger. All fear death. When you consider this, you will not kill or cause someone else to kill.”

Sri Lanka is said to be the crucible of Buddhism. So, can this country allow such carnage to take place to these gentle giants?

What do we tell our future generations, who may not be able to see these magnificent animals in the wild in the years to come?

Pix by Srilal Miththapala