Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 17 March 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A rare and endemic pygmy grasshopper illegally collected from Sinharaja World Heritage Site and published under the name ‘Cladonotus bhaskari’

Year 2020 was a bumper year for biopiracy. The year saw the publication in international scientific journals of no fewer than eight papers involving plant and animal specimens illegally collected and exported from Sri Lanka.

Year 2020 was a bumper year for biopiracy. The year saw the publication in international scientific journals of no fewer than eight papers involving plant and animal specimens illegally collected and exported from Sri Lanka.

These exports involved almost 20 species, mainly comprising invertebrate animals, in addition to a single species of fungus. In all, there have been at least 15 such papers since 2018, involving a total of more than 3500 specimens belonging to some 80 species, all illegally collected and smuggled out of Sri Lanka.

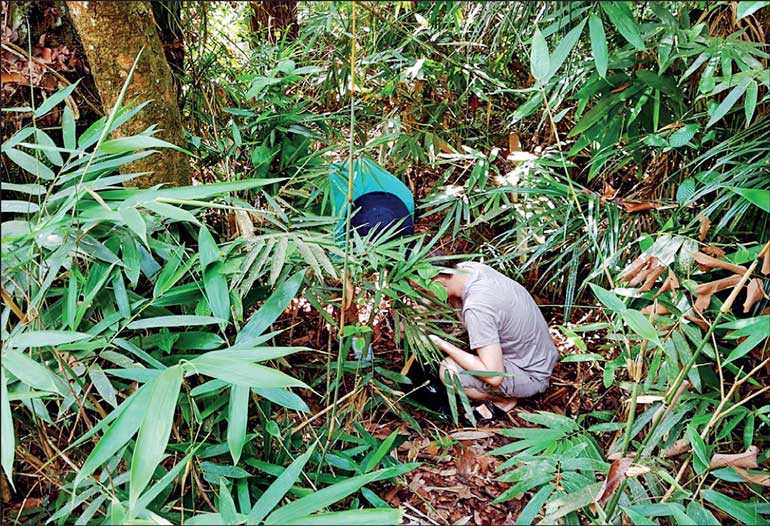

All the target specimens belong to species that are small and easily smuggled through airports. In the main, they seem to have been exported by foreign collectors disguised as ‘tourists’, operating without the necessary research permits from the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC).

While all Sri Lankan biodiversity researchers obtain permits for their research and, where necessary, exports (e.g., for genetic analysis), foreign scientists in search of Sri Lankan specimens seem to operate mostly outside the law, arriving as tourists and leaving with bags full of specimens.

Several such ‘tourists’ have been caught in the act of collecting specimens over the past few years and been successfully prosecuted by DWC.

Clearly, however, a much larger number get away with the stolen specimens. Although the DWC has been known to issue collection and export permits to foreign scientists, it seems that many scientists simply do not bother to apply.

As a result, for example, Dr. Bernhard Huber of the Alexander Koenig Research Museum of Zoology, in Bonn, Germany, published a monograph in 2019, describing 14 new species of pholcid spiders (permit WL/3/2/37/16). Similarly, Frantisek Kovarik, a private scorpion enthusiast from the Czech Republic, published descriptions of six new species of endemic Sri Lankan scorpions collected and exported from Sri Lanka in 2016, with a further one collected in Yala National Park subsequently (permit WL/3/2/79/14).

Such work is valuable because it serves to complete the country’s biodiversity inventory. And given that such permits are issued by DWC, there appears to be no reason for illegal collections to be made by foreign nationals. But piracy has seen a dramatic increase in recent years. Sadly, biodiversity-rich countries such as Sri Lanka have little protection against such acts.

It is impossible to monitor tourists everywhere they go without damaging tourism itself. But if tourists keep exploiting Sri Lanka’s legendary hospitality, they risk being treated with increasing suspicion. This is not good for tourism. As the COVID-19 pandemic draws to a close, we desperately need the $ 4.5 billion tourism used to bring into our economy annually. This is possible only if we are a tourist-friendly country. Sri Lanka is, however, not alone.

Other biodiversity-rich countries too, are affected, and some have chosen a different, more proactive approach to curbing this problem. In the last few months, Malaysian, Indonesian and Philippine authorities complained to the editors of the ‘Journal of Natural History’, the ‘Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity’ and ‘Zootaxa’ about papers published in them involving specimens that had been exported without the requisite permits (all these are prestigious biological journals; disclosure: I serve Zootaxa as an editor for freshwater fishes).

The former two journals ‘retracted’ the papers, invalidating them and deleting them from the scientific record. The last is still considering how to respond. The retraction of a published paper for reasons of ethics violation is one of the worst punishments that could be dealt out to a scientist. It leaves a permanent black mark on his or her record.

If the Director General of Wildlife were to write to the editors of the journals that published the 15 papers mentioned above, it is likely that most of them would be retracted. Further, writing to the foreign institutions (universities, museums, etc.) in which these illegally-exported specimens are stored may result in their being repatriated to Sri Lanka. Such action on the part of Sri Lanka is likely to cause enough publicity across the scientific world to dissuade any future ‘tourists’ from illegally collecting specimens in Sri Lanka.

However, we need to realise that specimen-collections are a necessary part of biodiversity studies. For example, it is impossible to understand Sri Lanka’s fauna and flora without a thorough understanding of India’s biodiversity.

So, India-Sri Lanka scientific collaboration is essential, and DWC should facilitate such initiatives. When well-monitored, collaborative research is officially sanctioned, it stimulates science while disincentivising illegal activities. There is a broad consensus across civil society in Sri Lanka that our country’s unique biodiversity must be protected and conserved for future generations. As such, we need to exert every effort to discourage biopiracy.

But we need to be careful not to treat all tourists as potential bio-pirates because of the handful of people who give tourism a bad name. The threat needs to be assessed carefully and an appropriate response crafted. Following the lead set by the Malaysian, Indonesian and Philippine authorities may be a good place to start.

Research in the guise of tourism: A foreign scientist making collections near Thambadola Ella, near Polgampola