Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 10 January 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“We have opponents. There can be no mercy allowed them. On the contrary, there is only one possibility: either we fall, or our opponent falls. We are aware of that, and we are men enough to look this knowledge straight in the eye, cool as ice. And that differentiates me from those gentlemen in London and America; if I demand much of the German soldier, I am demanding no more than I myself have always been ready to do also.”

“So, if Mr. Stalin expected that we would attack in the centre, I did not want to attack in the centre, not only because Mr. Stalin probably believed I would, but because I didn’t care about it anymore at all. But I wanted to come to the Volga, to a definite place, to a definite city. It accidently bears the name of Stalin himself, but do not think that I went after it on that account”

– Adolf Hitler, 8 November 1942 – from his speech on the occasion of the 19 anniversary of the ‘Beer Hall Putsch’

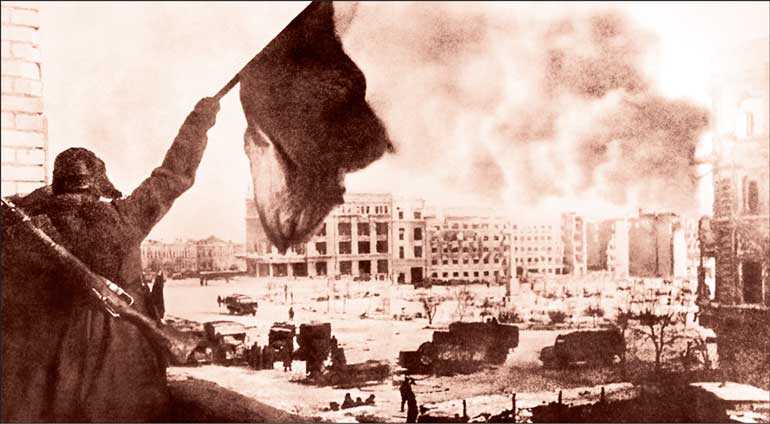

Seventy-seven years ago, in the freezing winter months of November 1942 to February 1943, a battle of unparalleled ferocity was waged in the devastated city of Stalingrad, which was to determine the outcome of the Second World War, and perhaps even the course of world history.

The battle for this fateful city had begun a few months earlier, when advance units of the German 6th Army, having crossed the river Don, dashed to the northern suburbs of Stalingrad, the great city on the shores of the Volga River. Their relentless drive East had now brought the Germans to the boundary of the Asian continent. It was an exhilarating moment for the proud and battle hardened soldiers of the Wehrmacht who had been marching since the mid- summer month of June (1942), when they jumped the river Donets and began their great southern offensive towards Stalingrad and Caucasus mountains.

When Germany launched their war against the Soviet Union the previous year, in June 1941, Stalingrad was not even on their war maps, their primary targets being Leningrad, Moscow and the Ukraine. In an exceptional feat of arms, in just six months of fighting they conquered most of the Ukraine and lay siege to both Moscow and Leningrad.

The sheer immensity of the land they had to conquer, exhaustion brought about by ceaseless effort and the gruelling winter, slowed and eventually denied the Germans the prizes they sought. In December 1941, when German thrust was at the end of its momentum, the Russians launched a massive counter offensive before Moscow, throwing the Germans back in disarray. However, soon they rallied and stopped the Russians, but paid heavily in men and material, in the course of intense winter fighting.

As the surprise Soviet counter-offensive of the winter of 1941 petered out in the freezing snows of the Russian wilderness, the minds of the German war planners began to turn to the inevitable summer campaign ahead, their successive offensive against a bloodied but defiant enemy.

1941

On 22 June 1941 the awesome German war machine, seemingly unstoppable, had launched itself at Russia (Soviet Union)-the largest country in the world, with a sudden and devastating ferocity. For this unparalleled attack the Germans had divided their four million strong striking force into three large army groups. Army Group North was to dash up to Leningrad, while bringing the Baltic area under its heel. The task of the exceptionally strong Army Group Centre was to thrust in to the Russia heartland with Moscow as the desired long stop. The Donets River was the ambitious summer target for the Army Group South, with Ukraine and Crimea as the rich prizes.

Only from an army of the calibre of the German Wehrmacht could a task of such sweeping ambition be demanded. No army in history had to conquer a land as vast, and an enemy as formidable, in just one furious campaign. To even contemplate such an undertaking, the attacker had to possess outstanding soldiery, combined with a capacity for extraordinary efficiency. Germany was obviously blessed with both.

The war opened dazzlingly for the Teutonic warriors. Punching huge gaps in the bewildered enemy defence lines, the formidable Panzer divisions of the Germans streaked across the Russian plains leaving the mopping up to the slower infantry divisions. These highly-trained men of the infantry, while fighting, regularly marched 30 miles a day, determined to keep cohesion with their comrades in the armoured units, relentlessly moving eastward.

But the country, that Germany had now locked horns with, was enormous, and the enemy exceedingly tough. The Russians fought with desperate courage, proving themselves to be exceptionally hard and resourceful fighters. It is testimony to the superlative quality of German arms that they, hopelessly over-stretched after six months of continuous fighting, almost achieved victory. In the north they surrounded Leningrad and imposed a crippling siege on the city. In the centre, German reconnaissance units stomped through knee high snow to the out- skirts of Moscow. In the south, most of Ukraine was theirs.

But the Russian bear, though dreadfully mauled, was refusing to lie down.

In this huge gamble the Germans had taken, even a near victory, amounted to a long term defeat. Although they were now deep in Russia, given the size of the country and its seemingly endless human resources, the enemy was still in a position to continue resisting strongly. The failure of the Wehrmacht to achieve total and essential victory in 1941 now necessitated a renewed offensive, which had to bring the enemy to heel once and for all. But after the dreadful winter battles of 1941, when Russians launched quite an effective counter punch, the Germans were not in a position to renew the attack on all three fronts. After much consideration they picked on the economically vital Southern Front, hoping their superior military could administer such a crippling blow to the Russians that they would be compelled to surrender. The Army Groups North and Centre were to remain on a defensive posture with a few local offensives to keep the Russian defenders pinned down.

1942

For the gigantic attack of 1942, the Army Group South was reorganised with Field Marshall Von Bock in overall charge. Under his command were several armies including the 2nd army, 17th army, the 6th army, the 1st Panzer army and the 4th Panzer army. Each of these armies was capable of delivering a crippling blow to the enemy, while the 6th was particularly strong with 11 divisions and an entire Panzer Corps in its establishment.

Operation Blue as the plan was named, though somewhat vague on its final objectives, envisaged among other things, reaching the Volga, bringing the large city of Stalingrad under control and gaining the Eastern Caucasus during the campaign. Again it was hoped that by menacing this vital area, they could compel the Soviets to commit its precious reserves, presenting the Germans with an opportunity to force the issue.

The Germans had no doubts about the superiority of their fighting men. Repeatedly, they had observed the wooden orthodoxy and the clumsy battle tactics of the Russian commanders. In contrast, the Germans were trained and encouraged to fight resourcefully. When necessary, their commanders did not hesitate to adopt bold initiatives and unconventional methods. Rather than attempting to overwhelm the enemy with superior numbers or often wasteful firepower, the Wehrmacht embraced the idea of effectively paralysing their foe with numbing speed.

On 28 June 1942, on an overcast day, Von Bock opened his offensive with predictable ferocity, within days splitting the Russian front in to rapidly disintegrating fragments. Once again the vaunted armoured divisions of the Germans advanced East across the massive steppe seeking an opportunity to mortally wound the enemy. Not only were they assured of their military supremacy, the Germans were also convinced of their racial superiority over an enemy their internal military magazines routinely described in disparaging terms such as- “degenerate looking Orientals, begging whining Asians, a mixture of low and the lowest humanity, truly subhuman”.

On 22 August 1942 elements of the German 6th Army, now under command of General Paulus, reached the Volga, in the borders of the Asian continent, a remarkable advance since June of 1941. Stalingrad, the city carrying the name of the Soviet dictator was in sight, tantalisingly within grasp.

On the 23rd of August, with predictable efficiency, the German Air Force began carpet-bombing the ill-fated city. The resulting fires turned Stalingrad in to a burning inferno of collapsed buildings, rubble and thick smoke. No human force could resist the German firepower in those conditions. Hitler who had baulked at the idea of committing his troops to city fighting in Moscow and Leningrad the previous year, now decided that he must have Stalingrad. Perhaps less sanguinely, but certainly with grim determination, Stalin had also decided that Russia would retreat no further.

So began the epic struggle between these two implacable enemies for a burnt out patch of the earth, which finally became the turning point of the Second World War. For the valiant Russian defenders there was little choice. They faced the fury of the German guns well aware that retreat only meant drowning in the freezing waters of the Volga. Besides, Stalin who knew how to impose his will, had placed Secret Service Police detachments in the rear with strict orders to summarily execute any Russian soldier disobeying the order to hold their ground to death. Such was their iron determination to give no further ground that the Russians during the battle of Stalingrad executed nearly 14,000 of their own men, for the offence of showing cowardice.

For the Germans, the battle for Stalingrad turned their world upside down. Their armoured divisions trained to capture something like 50 miles a day, were now advancing at snail pace, attempting to subdue burning city squares against an enemy who rarely showed himself. One single building would change hands several times in a day, each battle only adding to the corpses lying on the floor. In such close quarter fighting, German planes and tanks were often unable to join effectively, through the fear of hitting their own.

A Lieutenant with the German 24th Panzer division described the battlefield thus “Stalingrad is no longer a city. By day it is an enormous cloud of burning, blinding smoke; it is a vast furnace lit by the reflection of a million flames. And when the nights arrive, one of those scorching, howling, bleeding nights, the dogs plunge in to the Volga and swim desperately to gain the other bank. The nights of Stalingrad are a terror for them. Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for any longer; only men endure.”

While the fearsome battle was raging in this man made hell-hole of a burning city, hundreds of powerful German divisions were holding their impossibly long front line from the Baltic Sea to the Caucasus Mountains, unable to offer assistance. General Paulus himself could only commit eight of the divisions of the 6th Army to the crucial battle in the city, while assigning 11 divisions under his command to guard the large area under the Army’s administration and his exposed 200-mile-long flanks.

As the battle raged on in to the Russian winter, many a General warned of the dangers inherent in a prestige battle, where the German army was paying a price totally out of proportion to the city’s fast diminishing strategic importance. But the majority of the high command including Hitler, who held the Russians in contempt, could not conceive of a large-scale counteroffensive by them.

The Wehrmacht, which had traditionally prided itself on its cold rationality, was now acting increasingly on hateful prejudices, arrogance and unwarranted optimism. So General Paulus, the harried commander of the 6th Army, considered a competent staff officer, if slow-witted and unimaginative in the field, continued with tactics designed to grind down the enemy inch by inch, an approach which was essentially counter-productive to the numerically weaker, but technically superior Germans.

The German battle order in the Stalingrad area now presented Marshall Zhukov the Russian commander, legendary for his coolness under pressure, with a situation where he could turn tables on the enemy. The German 6th Army intent on gaining Stalingrad at any cost, was fully absorbed in city fighting. Its long and difficult flanks guarded mainly by satellite divisions from Rumania and Hungary, with only a sprinkling of overstretched German units for strength, were vulnerable. These satellite armies were far inferior to the Germans in fighting qualities, as well as in equipment. The nearest German formations of any size, were far away in the Caucasus absorbed in heavy fighting in the mountains.

Realising the opportunity, the situation presented, Zhukov decided to keep the battle of Stalingrad going even at such a heavy price, while secretly accumulating huge forces at the extremities of the German flanks. It was a hard decision. The men he ferried across the Volga to battle the Germans in the inferno of Stalingrad had extremely low chances of returning alive. But in order to keep the Germans firmly focused on the city, Zhukov was willing to pay with blood, for time. So for almost four months, the two armies continued to wage a ferocious battle for the few remaining square miles of the city of Stalingrad.

Then, in the early hours of 19 November 1942, when the freezing Russian winter was well advanced, Zhukov struck. The Russians, in two huge pincer attacks, pierced the flanks of the 6th Army moving rapidly towards Kalach, their intended meeting point. On their advance they met only feeble resistance from the Rumanians/Hungarians, the allied troops to whom the Germans had mainly entrusted the task of guarding the rear of the 6th Army.

On 22 November when the two pincer arms of the Russians met at the farming town of Kalach, they had entrapped the great 6th Army of the Germans. In the bleak, snow covered Russian Steppe, under a numbing winter mist, the turning point of the Second World War had been reached. Although, numbers given by various sources vary, nearly 300,000 Axis soldiers were lost in the great entrapment. It is reported that there were nearly 600 German doctors alone in the pocket, a pointer to the size of the sixth army’s deployment.

Although the Germans were to fight on doggedly for another two-and-a-half years, they had irretrievably lost the initiative. Despite valiant attempts six months later in the titanic battle of Kursk to wrestle back the initiative, from Stalingrad on, the Germans were largely an Army in defence.