Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 14 September 2021 01:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Oxford-educated prominent economist Deshamanaya Prof. W.D. Lakshman has certainly dented his reputation

Central Bank of Sri Lanka Governor Prof. W. D. Lakshman in a virtual media conference reported in the print media announced that he would resign from the post next week. He noted that Sri Lanka continues to be a developing nation because there are no underlying systems, processes and compliance structures in place and that no one can agree on a long-term policy.

Central Bank of Sri Lanka Governor Prof. W. D. Lakshman in a virtual media conference reported in the print media announced that he would resign from the post next week. He noted that Sri Lanka continues to be a developing nation because there are no underlying systems, processes and compliance structures in place and that no one can agree on a long-term policy.

Further he noted: “If you take a look at what happened over the past two weeks, this also played a role in my decision. If I decide to open up, I will comment on the reasons for my retirement, later.”

His resignation comes at a time when businesses are complaining that the banks are playing hide and seek with the foreign currency leading to an exacerbating of the volatility between the black and white forex markets in the country. Prof. Lakshman however omitted to even mention that during his tenure CBSL became a virtual printing press expanding the money stock by 2.8 trillion or over 35% (Daily FT – W.A. Wijewardena 13 September 2021).

During his tenure however, the financial sector over which the Central Bank provides oversight did a decent maintenance job given the extraordinary situation the country was in – i.e. the pandemic. Hardly any reforms happened and to some extent the discipline in the sector took a step back. With hindsight, the unassuming academic that was Prof. W. D. Lakshman was certainly not cut out for the role at this time.

Banking sector reforms

In 2003, when I became a director of a listed development bank and two years later a director of a listed commercial bank, the complexity of the banking governance requirements were not as onerous as it is today. It was possible to be a director of two banks at the same time.

With the changes that came in 2008-2010, the discipline in the sector was strengthened and the old boy network disbanded. The sector was forced to change. Statutory committees within the boards were mandated to provide oversight on financials, compensation, risk and compliance and governance. Directors were forced to keep in focus that depositors’ and lenders’ money accounted for nearly 90-92% of the capital employed. In lieu of this share ownership restrictions were imposed with a maximum of 15%.

Ironically, these rules did not apply to the government shareholders. This led to the interference by successive governments and their bureaucratic layers, to influence lending, decision making and appointments. Nothing much has changed unfortunately in the DNA of the banks.

For a start, if a competent board is appointed they must then have the freedom to operate towards the wellbeing of the institution, not to be subservient to powerful shareholders – private, state or acting in concert. Lending and delinquency management must be independent of the owners/shareholders/.

Many of the reforms proposed by the Banking Sector Consolidation Committee of 2016-’17 were never implemented. For a start the rules that apply to private shareholders must apply to State sector shareholders. The Government has two State banks to drive the national agenda, instead of using the private commercial banks.

The country badly needs a fully-fledged national development bank to ensure a long-term robust credit supply to facilitate the recovery. The privatisation of the development banks was a costly mistake of the reform agenda.

The way forward

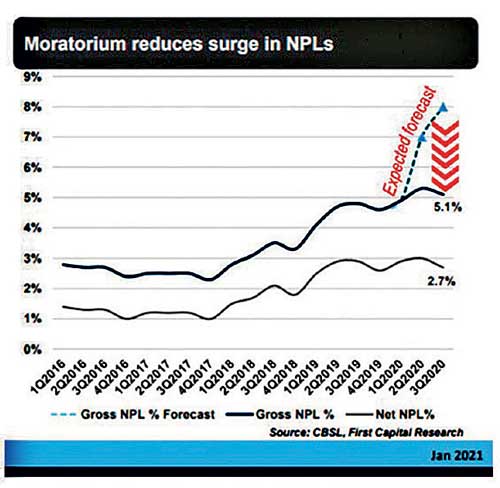

The COVID-19 pandemic was a major test to our financial system; the pandemic is not yet over and its economic and financial impact will play into 2022. Thus far the financial system has weathered the pandemic thanks to greater resilience from high capital buffers from BASL III and a bold CBSL policy response. The financial sector has surprised the analysts by reporting hefty profits despite tourism moratoriums and delayed loan recovery due to the pandemic.

According to Fitch Ratings, the national ratings on Sri Lankan banks remain constrained by the sovereign credit profile (CCC). Banks have however maintained strong capital positions during the pandemic and largely did not face large liquidity pressures because of the CBSL’s defensive actions to maintain liquidity levels well above regulatory minimum.

In the pandemic, banks and NBFIs are providing an important life line to individuals and businesses. Whilst expectations are huge, banks have an overwhelming responsibility to honour deposit payments whatever the currency in a timely manner. Banks cannot be expected to give prolonged moratoriums and honour this commitment. This is why a development bank that has long-term funding lines is urgently required.

The tourism sector will certainly recover by 2023-’24. The tourism industry is critical for the well-being of the country. They need therefore to be supported not by just extending moratoriums, but very much more. There are many options on the table. This is why the CBSL’s independence and leadership is so crucial for the future of the financial sector.

The irony is that the length of the current health pandemic and the depth of its severity is still unknown, therefore the financial sector must anticipate certain amount of adjustment/changes to their business model and balance sheet following the crisis to ensure that their partners also comes out of the crisis as winners. The challenges ahead for the next Governor are certainly humongous.