Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 3 February 2021 00:14 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central Bank has taken unprecedented monetary policy measures to ease credit access and to reduce borrowing costs with the intention of raising private investment so as to revive economic activity.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central Bank has taken unprecedented monetary policy measures to ease credit access and to reduce borrowing costs with the intention of raising private investment so as to revive economic activity.

But the private sector demand for bank loans does not seem to be picking up adequately due to the uncertain market conditions in the backdrop of economic fallout from the pandemic and the global economic setback.

To make matters worse, the deterioration of the rupee in recent weeks amidst mounting debt commitments diminishes investor confidence, as explained in my previous column in Daily FT (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Rupee-is-under-stress-with-mounting-debt-commitments/4-712268).

Monetary easing measures

The relief measures provided by the Central Bank since early last year to the households and businesses hit by the pandemic have been quite extensive. It has implemented a series of monetary easing measures including sequential reductions of the policy interest rates and Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR), thereby injecting substantial liquidity into the market and significantly lowering borrowing costs.

Concessional credit schemes were also introduced to facilitate the activities of Small and Medium-scale Enterprises (SMEs), alongside debt moratoria granted for businesses and individuals distressed by the pandemic.

Further, the Central Bank has accommodated government finance requirements by directly purchasing Treasury Bills at several primary auctions.

Private sector credit growth slowing down

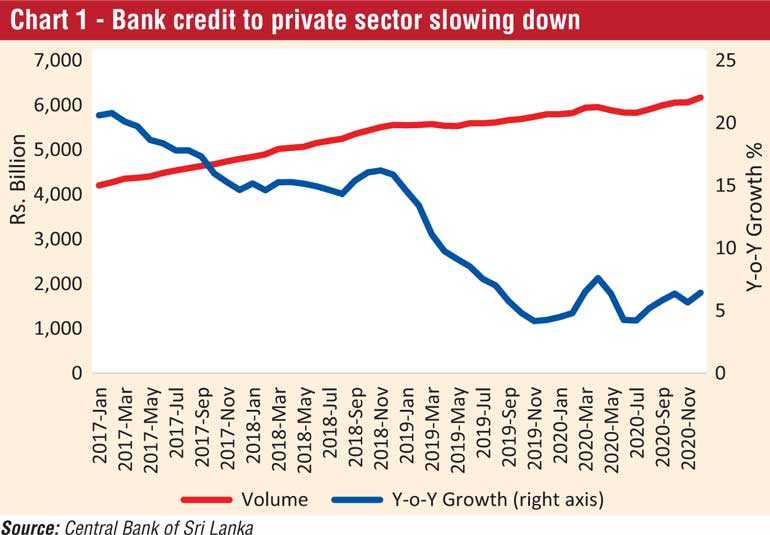

Deceleration of bank credit to the private sector was evident even before the outbreak of the pandemic reflecting the long-term downturn of economic activities. Year-on-Year (Y-o-Y) growth of private sector credit was down to 4.5 in January 2020 from a peak level of 20.6% two years ago (Chart 1).

Following the monetary easing measures adopted by the Central Bank in early 2020, the private sector credit growth surged to 7.6% by April 2020. But it fell again to 4.2% in July 2020, and hovered around 6.0% during the last quarter of the year.

The continuation of the pandemic has delayed regular business activities indefinitely, and thus, entrepreneurs seem to be reluctant to fully utilise bank credit even at low cost.

Credit to public sector rising rapidly

In contrast to the downward trend in private sector credit growth, the Government has been increasingly relying on bank credit to finance its budget deficit triggered by substantial tax cuts.

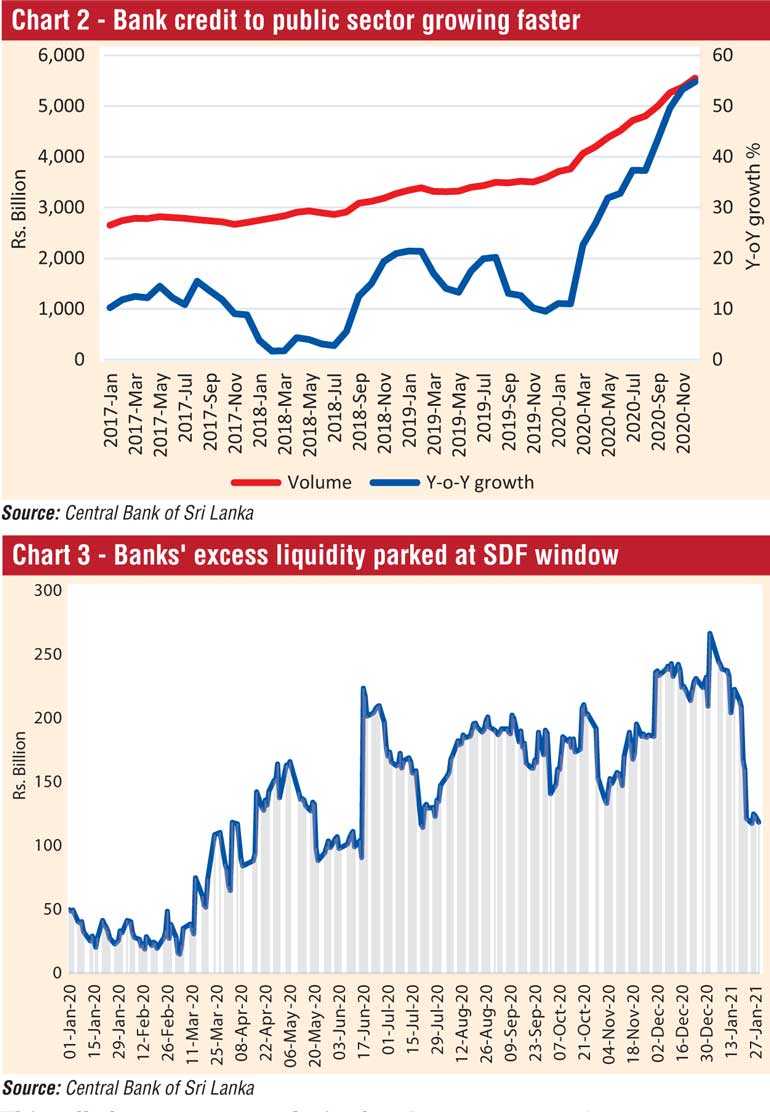

Thus, bank lending to the Government and public corporations has risen at a rapid pace (Chart 2). The Y-o-Y growth of lending to the Government was as much as 64.4% by the end of 2020, compared with only 9.9% a year ago.

Bank finance is also used in large scales to run the loss-making state-owned enterprises. The Y-o-Y growth of credit to public corporations reached 22.5% at the end of 2020 from 8.3% a year ago.

As a result, the public sector has overcrowded the financial market preempting resources from the private sector. In fact, the Government has immensely benefited from the prevailing low interest rate environment to finance its growing budget deficit at low cost.

Meanwhile, the plight faced by the individuals in low-income categories depending on interest earnings in this situation is a matter of concern.

Excess market liquidity has adverse consequences

Growing credit to the public sector has brought about a rapid increase in the money supply causing excess liquidity in the economy. The money supply rose by as much as 23.4% in 2020, compared with 7.0% in 2019. Money supply as a ratio of GDP, which reflects market liquidity, rose from 46% in 2019 to around 54% in 2020. It is likely to be as much as 63% this year, according to the author’s projections.

The excessive growth of money supply in such manner has adverse implications for external balance and inflation. Effects of excess liquidity on the balance of payments are not felt yet due to import restrictions and lesser import demand for intermediate and investment goods due to the production setback. Once the economy returns to normality, much larger import volumes could be expected with adverse consequences on the external balance.

The emerging demand pressures and supply shortfalls are reflected in the headline inflation of the National Consumer Price Index which rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 6.2% in 2020.

Forward contracts banned

The rupee depreciation has become so severe in recent weeks that the Central Bank directed commercial banks to refrain from entering forward contracts of foreign exchange for a period of three months with effect from 25 January 2021.

Although this measure was claimed to be implemented to reduce exchange rate volatility, the forward markets, on the contrary, are widely used as a buffer to minimise foreign exchange risks and thereby to maintain exchange rate stability across major global forex markets.

Continuous foreign exchange tightening in such manner might give improper signals to the market adversely affecting investor confidence, thereby nullifying the anticipated beneficial effects of the Central Bank’s monetary easing measures. In other words, private sector demand for bank loans will continue to remain stagnant despite the rate cuts amidst market uncertainty.

Credit risks

The Central Bank drastically reduced the SRR from 5% to 4% in March 2020 and again to 2% in June 2020. SRR is the proportion of the deposit liabilities (demand, time and savings deposits) that commercial banks are required to keep as a cash deposit with the Central Bank. This together with other policy stimulus including six-month debt moratorium are expected to boost private sector credit.

Simultaneously, there is possibility of weakening the banks’ asset quality with rising Non-Performing Loans (NPL). The gross NPL ratio was rising even before the pandemic from 3.4% at the end of 2018 to 4.7% by the end of 2019. Then, it went up to 5.3% at the end of the third quarter of last year.

Such credit risks partly explain the slow growth of private sector credit, as banks seem to be cautious in delivering credit to risky businesses during the pandemic. Allowing for adequate risk premium to cover loan defaults, banks and other financial institutions may find it difficult to drastically reduce their lending rates, as anticipated by the Central Bank. This calls for a separate analysis of lending rates.

Meanwhile, commercial banks have a much safer lending destination, i.e., Government debt instruments. As explained earlier, bank credit to the Government rose rapidly in recent months.

The balance funds remaining as excess liquidity in commercial banks are conveniently parked in the Central Bank’s Standing Deposit Facility (SDF) window (Chart 3). Such risk-less deposits presently earn interest at 4.5% per annum.

Modified monetary policy stance needed

Business enterprises, particularly those in the small and medium sectors, as well as the poverty-stricken households would have been worse off following the pandemic, if not for the monetary easing measures carried out by the Central Bank.

Nevertheless, the Central Bank needs to supplement such interim policy measures with a coherent monetary policy framework – perhaps a modified version of the previously initiated Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) framework in conjunction with a firm commitment of the fiscal authorities to reduce the budget deficit to smoothen the post-pandemic economic order.

Mopping up of growing excess liquidity should be a priority area in such modified monetary policy framework.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)