Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 6 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

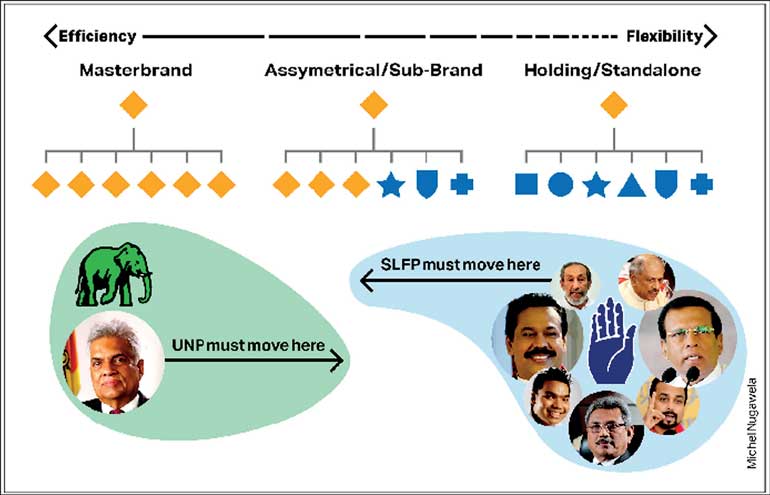

Politics, as they say, makes strange bedfellows but can the increasingly fractured Yahapalanaya Government survive the next general election? The organisational logic of a brand architecture strategy can clarify the offerings of both parties and guide efforts to manage and maximise the value of their relationship.

Politics, as they say, makes strange bedfellows but can the increasingly fractured Yahapalanaya Government survive the next general election? The organisational logic of a brand architecture strategy can clarify the offerings of both parties and guide efforts to manage and maximise the value of their relationship.

Political parties closely resemble company-wide masterbrands. They encompass a wide range of beliefs, factions and interest groups under a common symbol, much like Land Rover’s well-diversified portfolio targets serious off-road enthusiasts with the Defender and status-seeking yuppies with the Range Rover Evoque.

Examples such as Land Rover (or Ford, Gillette and Kelloggs) demonstrate how brand custodians carefully develop their portfolio strategies to ensure that individual product lines do not obscure or compete with the identity and positioning of the masterbrand. A narrow definition of its TG – “an active male, high net worth demographic between the ages of 34-54” – enables Land Rover to continue developing sub-brands for diverse sets of consumers who share the experience or appearance of adventure. In branding, the trick is to manage how sub-brands can add to or modify the associations of the masterbrand.

This is the very challenge that President Maithripala Sirisena faces as he contends with a powerful Rajapaksa faction – the Mahinda sub-brand – that appears to have become bigger than the SLFP masterbrand that hosts it.

Over the years, and quite unwisely, the party has enabled extremists and opportunists to reach a critical mass of power. Coalitions can be powerful currency for smaller parties that have little chance of gaining power, but they exact a heavier price from national organisations like the SLFP which are required to make greater policy compromises, emphasise and defend the coalition record, explain their philosophies, and organise people to vote.

By identifying itself so closely with the UPFA, the SLFP has won elections but progressively lost its identity, which today is dwarfed by personalities – or sub-brands – who compete to secure and wield power, often at the expense of a stronger party organisation. This simple inverse relationship also informs the organisational logic of a brand portfolio: a strategy of proliferating sub-brands only works at the expense of the masterbrand.

Interestingly, as the SLFP masterbrand is obscured by its unruly sub-brands, the UNP emphasises a rigid masterbrand strategy that maximises control over its portfolio. The Party Leader and Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, has no sub-brands to contend with – unlike former UNP Leader J.R. Jayewardene, who managed a portfolio of charismatic personalities like Lalith Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake.

Similar to auto giant BMW’s line extensions that vary only in price, quality and features – 3 (small), 5 (medium), 7 (large), M (high performance), Z4 (roadster) and X3/X5 (SUV) – today’s UNP maximises awareness through a single purpose and image that mirrors Mr Wickremesinghe’s continued resistance to populism and adherence to democratic pluralism. Efficient and consistent? Certainly. Able to connect with new target groups and segments? Unfortunately not, for masterbrands work best when they target consumers that share similar category structures. It is sub-brands that create opportunities to reach, build and sustain relationships with new audiences. It is sub-brands that connect to new trends, ideas, beliefs and values which appeal to different voter groups, and, in turn, positively add to or modify the associations of the masterbrand.

In fact, it is the very absence of sub-brands within the UNP – energising new viewpoints, beliefs, and philosophies that are propagated by winsome personalities – that hinders the party from enriching its masterbrand with new and productive values. If the UNP is to be perceived as a socially progressive party, it must admit more intellectually ambitious and compelling personalities into its ranks. And if it is to appeal to younger voters, it must give prominence to more youthful leaders.

Both the SLFP and UNP must redefine themselves to reignite meaning and recapture the public imagination. Both parties require productive masterbrands that honour their equities while appealing to diverse audiences.

For the UNP, the objective is a branding strategy that increases market share by reaching a larger, more diverse audience; this can be achieved through a greater role for its sub-brands. For the SLFP, the objective is a strategy that maximises its equity and brings greater unity and efficiency to its portfolio; this, however, requires greater control and rationalisation of its sub-brands. If both find this balance, and through it a common purpose, they would be stronger partners within an important National Coalition Government that continues to keep the extremists at bay.

(The writer is CEO, MND/Sri Lanka partner for Interbrand.)