Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 6 April 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

State Minister Arundika Fernando

State Minister of Coconut, Kithul, Palmyrah and Rubber Cultivation Promotion and Related Industrial Product Manufacturing and Export Diversification Arundika Fernando was wrong in asking ASP Eric Perera to go easy on small-scale producers of illegal liquor.

State Minister of Coconut, Kithul, Palmyrah and Rubber Cultivation Promotion and Related Industrial Product Manufacturing and Export Diversification Arundika Fernando was wrong in asking ASP Eric Perera to go easy on small-scale producers of illegal liquor.

As ASP Perera correctly explained, police officers cannot make arbitrary distinctions between law breakers who are small scale and who are not. This country is plagued by abuse of prosecutorial discretion. It is wrong to demand that investigatory discretion be further abused too.

But the State Minister has a point. We should not be misdirecting scarce police resources on prosecuting producers of alcoholic beverages. We should change the law to reduce the financial incentives of operating illegal stills.

The Minister of Public Security was wrong to transfer a law-abiding and apparently efficient senior police officer. Instead of engaging in such actions harmful to the efficient functioning of government (another consequence of the 20th Amendment), he should have focused his attention on the parlous state of law and order in this country.

More than half of the police force of over 88,000 is still deployed on VIP security almost 12 years after the decapitation of the LTTE; and 30 years after the decapitation of the DJV, the military arm of the then JVP. Laws are not enforced without fear or favour. Most people are told to catch the law breakers and bring them to the police station. Sometimes the police are a greater threat to citizens than criminals.

The story of Scotch

Most decision-makers in this country have a liking for Scotch whiskey. Therefore, the story of Scotch may be more persuasive than the stories of arrack and baijiu (which will also be told).

As the distilling of whiskey became more popular in Scotland, legislators sought a piece of the action. The first taxes on Scotch were introduced in 1644 which led to an increase in illicit whisky distilling across Scotland. By the 1820s, as many as 14,000 illicit stills were being confiscated every year. More than half the whisky consumed in Scotland was illegal. It was even said that King George IV drank nothing but illegal Glenlivet.

In 1823 the Excise Act was passed, which permitted the distilling of whisky on payment of a license fee of GBP 10, and a set payment per gallon of proof spirit. Next time you partake, examine the label. It is likely that the bottler of your favourite beverage traces its origins to around 1823.

Even after COVID-19 and a punitive tariff imposed by the United States, earnings from the export of Scotch whiskey amounted to GBP 3.8 billion in 2020. The year before, it was GBP 4.9 billion. This does not include earnings from related activities such as whiskey tourism. Over two million visits to Scotch distilleries per year were reported before the pandemic hit.

The story of arrack

The story of arrack

Arrack manufacturing was developed during Dutch rule of the coastal areas. Exports grew rapidly under early British rule. Unlike its Scottish counterpart, the Excise Ordinance of 1834 consolidated legal production in a few large companies and made the pot still distillers illegal. Exports ceased.

It is possible that concerns over quality of the product, including periodic methanol poisoning, led to restrictive licensing. The manufacturing and consumption of hali arakku (arrack from pot stills), derogatively described as kasippu, was a major element of life in the coastal belt. The battle between the police and illicit distillers was never ending. When the men got incarcerated, women ran the business.

It is this ancient tension that Arundika Fernando gives voice to. People believe the Government-sanctioned liquor is too expensive or that its quality has been compromised because of the incentives set in place by the excise taxes. Or they simply prefer the taste of the local product. The gap between what the Government-sanctioned liquor is sold for and the cost of producing hali arakku is large, permitting significant expenditure on bribes.

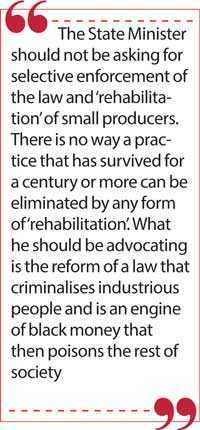

The State Minister should not be asking for selective enforcement of the law and ‘rehabilitation’ of small producers. There is no way a practice that has survived for a century or more can be eliminated by any form of ‘rehabilitation’. What he should be advocating is the reform of a law that criminalises industrious people and is an engine of black money that then poisons the rest of society.

Reform the law

There are reasons to worry about excessive consumption of intoxicants. People can get sick and, in a publicly funded healthcare system like ours, the costs of treatment will be borne by all. People have been using intoxicants of various forms throughout history, suggesting that stamping out the practice is unrealistic. Yet it is wise to do things like control advertising of alcohol, which Sri Lanka has been doing since the 1990s, and to promote moderation.

It is unlikely that the Sri Lankan excise and police authorities will ever be able to fully stamp out pot still production. The resources needed for stronger enforcement would cause further harm to the weakened law enforcement that exists today.

Government should look at a comprehensive solution that includes rationalisation of excise taxes, whereby what now goes under the table to politicians and police personnel comes to the State. Encouragement should be given to the development of premium brands associated with colourful narratives that can do well in export markets and even in the wealthier market segments within the country. Arrack-centric tourism should be promoted. Reduction of excise taxes combined with a reallocation of enforcement resources will create the right conditions for the needed focus on ensuring the quality of the manufactured output, putting a stop to what many believe to be rampant tampering. The world’s most consumed alcoholic beverage is not whiskey. It is Baijiu, the most famous brand being Moutai. What used to be quick way of getting drunk has been undergoing an extraordinary transformation in recent times, with all sorts of premium products and brands being developed and marketed outside China. Some bottles are priced in the thousands of dollars.

Sri Lanka’s arrack has greater potential than the Chinese firewater. But the potential cannot be realised only by the old established big companies. Legalising small producers and unleashing their innovative energy is the essential precondition for Sri Lanka regaining its position as an exporter of premium alcohol products from coconut, kithul, and palmyrah. The State Minister should proceed with confidence. If the President is against this kind of initiative, he would not have created a separate Ministry for Coconut, Kithul, Palmyrah and Rubber Cultivation Promotion and Related Industrial Product Manufacturing and Export Diversification. There is only so much you can do with coconut ekels.