Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 4 November 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

One of the most talked-about election promises this week has been Sajith Premadasa’s promise to distribute free sanitary hygiene products. Labelling himself as a #padman, Premadasa tweeted that “until sustainable cost-effective alternatives are found,” he promises to provide sanitary hygiene products free of charge.

Indeed, access to menstrual hygiene products is a serious problem in Sri Lanka, and has become a popular issue across political parties. In March this year, SLPP’s Namal Rajapaksa also tweeted about the issue, asking: “What rationale could a Gov have to tax half its populace on a dire necessity? Is the Gov aware of studies on poor hygiene practices & cervical cancer?”

Taxing menstrual hygiene

Although 52% of Sri Lanka’s population is female, with approximately 4.2 million menstruating women, access to safe and affordable menstrual hygiene products remains somewhat of a luxury for many Sri Lankan women.

A leading contributor to the unaffordability of menstrual hygiene products in Sri Lanka is the taxes levied on imported menstrual hygiene products. Sanitary napkins and tampons are taxed under the HS code HS 96190010 and the import tariff levied on these products is 62.6%.1

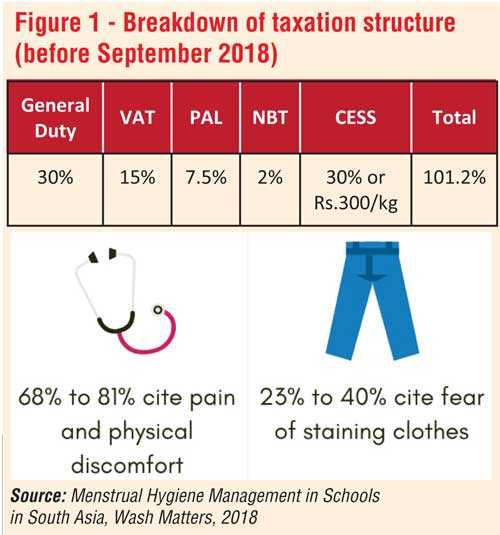

Until September 2018, the tax on sanitary napkins was 101.2%. The components of this structure were Gen Duty (30%) + VAT (15%) + PAL (7.5%) + NBT (2%) and CESS (30% or Rs.300/kg).2 In September 2018, following social media outrage against the exorbitant tax, the CESS component of this tax was repealed by the Minister of Finance.3 Yet, despite the removal of the CESS levy, sanitary napkins and tampons continue to remain unaffordable and out of reach for the vast majority of Sri Lankan women.

The average woman has her period for around five days and will use four pads a day4. Under the previous taxation scheme, this would cost a woman Rs. 520 a month5. The estimated average monthly household income of the households in the poorest 20% in Sri Lanka is Rs. 14,843. 6 To these households, the monthly cost of menstrual hygiene products would therefore make up 3.5% of their expenses. In comparison, the percentage of expenditure of this income category on clothing is around 4.4%.7

Internationally, repeals on menstrual hygiene product taxation are becoming increasingly common due to their proliferation of gender inequality and the resulting unaffordability of essential care items, commonly known as ‘period poverty’.8 Kenya was the first country to abolish sales tax for menstrual products in 2004 and countries including Australia, Canada, India, Ireland and Malaysia have all followed suit in recent years.9

The impact of unaffordability

The current cost of menstrual hygiene products in Sri Lanka has direct implications on girls’ education, health and employment.

According to a 2015 analysis of 720 adolescent girls and 282 female teachers in Kalutara district, 60% of parents refuse to send their girls to school during periods of menstruation.10 Moreover, in a survey of adolescent Sri Lankan girls, slightly more than a third claimed to miss school because of menstruation.11 When asked to explain why, 68% to 81% cited pain and physical discomfort and 23% to 40% cited fear of staining clothes.12

Inaccessibility of menstrual hygiene products also results in the use of makeshift, unhygienic replacements, which have direct implications on menstrual hygiene management (MHM). Poor MHM can result in serious reproductive tract infections. A study on cervical cancer risk factors in India, has found a direct link between the use of cloth during menstruation (a common substitute for sanitary napkins) and the development of cervical cancer13; the second-most common type of cancer among Sri Lankan women today.

The unaffordability of menstrual hygiene products is also proven to have direct consequences on women’s participation in the labour force. A study on apparel sector workers in Bangladesh found that providing subsidised menstrual hygiene products resulted in a drop in absenteeism of female workers and an increase in overall productivity.14

Towards a sustainable solution

If the Government is serious about finding sustainable solutions to the issues associated with unaffordability of menstrual hygiene products in Sri Lanka and promoting gender equality, it should be looking to slash the heavy import taxes currently levied on these products. Current taxation rates are keeping prices high and out of reach for a majority of Sri Lankan women. By reducing these rates, the cost of importing sanitary napkins and tampons will simultaneously decrease and stimulate competition in the industry, further driving prices down and encouraging innovation.

The conventional argument in favour of import tariffs is the protection of the local industry. However, in Sri Lanka, sanitary napkin exports only contribute a mere Rs. 25.16 million, or 0.001%, to total exports.15 Increased market competition would also incentivise local manufacturers to innovate better quality products and ensure their prices remain competitive for consumers.

Other common concerns pertaining to the issue of low quality products potentially flooding the Sri Lankan market if taxation is reduced are unlikely to materialise, since quality standards are already imposed by the Sri Lankan Government on imported products under SLS 111.

In addition, making these products more affordable would align with Sri Lanka’s commitment to Article 12(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which promotes the right of all individuals to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.16 By keeping prices high, present taxation methods are contributing systematic obstruction of many women’s right to equal opportunity to enjoy the highest attainable level of health, and thereby do not meet the ratified standards of the ICESCR.

If menstrual hygiene products are made more affordable, it is likely that more Sri Lankan women will be able to uptake their use. Sri Lanka should thus remove the remaining import levies on menstrual hygiene products as soon as possible, via the means of an extraordinary gazette.

Removing the PAL and General Duty components alone would bring taxation levels down by 43.9% to a total of 18.7. This would remove a significant barrier to girls’ education, women’s health and labour force participation, and create a wide-scale positive impact on closing Sri Lanka’s present gender gap and facilitating more inclusive economic growth. There has been a lot of rhetoric around keeping women safe and making them a priority this election – so what better place to start than this?

(Nishtha Chadha is a Research Intern at the Advocata Institute. Her research focuses on public policy, international relations and good governance. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Advocata is an independent policy think tank based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. They conduct research, provide commentary and hold events to promote sound policy ideas compatible with a free society in Sri Lanka. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, its Board of Directors, its Research Fellows or its Advisors.)

Footnotes

1 “HS Code Finder/Sri Lanka Customs”. Customs.Gov.Lk, 2019, http://www.customs.gov.lk/business/hsfinder. Accessed 11 June 2019.

2 Sri Lanka Customs. Tariff Guide 2019.03.15. Chapter 1: Section (6).

http://www.customs.gov.lk/tariffchanges/home. Accessed 14 Oct 2019.

“General duty = CIF value* customs duty rate

PAL (Port and Airport Development Levy) = CIF value * PAL rate

CESS levy = (value of the good +1 0%*value of the good) * CESS rate

Excise (Special provisions) duty = (value of the good + 15% of the value of the good + General Duty + CESS levy + PAL levy ) * Excise duty rate

Value Added Tax = value of the good + (1+10% of the value of the good + General Duty + PAL levy + CESS levy + excise duty) * VAT rate

Nation Building Tax = value of the good + 10% of the value of the good + General Duty + PAL levy + CESS levy + Excise duty) * NBT rate”

3 “Sri Lanka Lifts Tax On Sanitary Napkins”. Economy Next, 2018, https://economynext.com/Sri_Lanka_lifts_tax_on_sanitary_napkins-3-11961.html. Accessed 11 June 2019.

4 “A Woman’s Monthly Tax — Advocata Institute | Sri Lanka | Independent Policy Think Tank”. Advocata Institute | Sri Lanka | Independent Policy Think Tank, 2018, https://www.advocata.org/commentary-archives/2018/06/12/a-womans-monthly-tax. Accessed 12 Oct 2019.

5 Ibid.

6 Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016. http://www.statistics.gov.lk/HIES/HIES2016/HIES2016_FinalReport.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2019.

7 Ibid.

8 “Period Poverty: Everything You Need to Know”. Global Citizen, 2019. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/period-poverty-everything-you-need-to-know. Accessed 29 October 2019.

9 “Goodbye, Tampon Tax (at Least for Some)”. New York Times, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/09/health/tampons-tax-periods-women.html. Accessed 29 October 2019.

10 “Menstrual Hygiene Management In Schools In South Asia”. Wash Matters, 2018, https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/

WA_MHM_SNAPSHOT_SRILANKA.pdf . Accessed 11 June 2019.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Socio-demographic and behavioural risk factors for cervical cancer and knowledge, attitude and practice in rural and urban areas of North Bengal, India. Raychaudhuri S1, Mandal S. http://journal.waocp.org/article_26298_e73d70143926839642144a3724161d93.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2019.

14 Hossain, Md Irfan, et al. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the HERhealth Model for Improving Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Knowledge and Access of Female Garment Factory Workers in Bangladesh.” (2017).

15 Export Development Board Statistics, Export Database. (2018).

16 Assembly, UN General. “International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights.” United Nations, Treaty Series 993.3 (1966).

17 Calculations made by the Advocata Institute through the Tariff Calculator, Customs Department of Sri Lanka.