Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 15 November 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A discourse on restructuring Sri Lanka’s many governance structures, namely the president, the parliament, provincial councils, municipal councils and pradeshiya sabhas, is imperative considering the immense burden on taxpayers to maintain these institutions in the name of democracy.

The introduction of provincial councils under the 13th Amendment added an expensive nine chief ministers and 446 provincial councillors while recent amendments to the local government structure sent the number of local government councillors beyond the 9,000 mark.

In addition to the big burden on the Government’s recurrent expenditure bill, it is evident that the political culture of the elected members to these numerous institutions creates a substantial detrimental impact on the social fabric, particularly in rural areas.

The powers of the Executive Presidency have been lessened under the 19th Amendment and it was evident over the last five years of Yahapalanaya that the presidency has its own merits and demerits. I have an opinion on the presidential system reforms but this article focuses on practical reforms proposed to restructure the parliamentary and provincial council systems in order to achieve a lean democracy, reducing the burden on taxpayers. If implemented, the Government can divert colossal recurrent expenditure on provincial councillors towards development.

Provincial councils were introduced under the 13th Amendment as a power devolution tool designed to deliver a power sharing mechanism to ethnic Tamils in the North and East seeking self-rule. However, it is an established fact that by and large provincial councils are a white elephant and have not produced their intended outcomes after their implementation in the Northern and Eastern provinces.

The 13th Amendment and provincial councils were introduced in a hurry without substantial deliberations and as a result created an expensive second tier parallel governance structure in the country. There were 455 elected representatives added to the system, resulting in a heavy burden on Government expenditure.

It is not a practical move to abolish provincial councils or reform the powers vested under the 13th Amendment in a hurry due to the Indian sensitivity attached to it. However, it wise to explore all avenues to rectify key weaknesses in it. The preferential voting system menace and cost of maintaining 455 provincial councillors are critical issues that can be rectified by innovating a solution within the existing constitutional framework.

One national election for Parliament and provincial councils

Sri Lanka can have a lean democracy by electing a common set of electoral members to provincial councils and Parliament through a single national election. Members elected will be vested with devolved powers under the 13th Amendment as Members of Provincial Councils (MPCs) while discretely performing national legislative duties as Members of Parliament (MPs).

Only 250 MPs for both Parliament and provincial councils

With such convergence, the country can realistically limit the total number of elected members within both provincial councils and Parliament to 250. Almost the entire additional cost incurred by maintaining 455 provincial council members as a result of the 13th Amendment can be saved through such an arrangement. The number of State-paid people’s representatives and their numerous other costs such as payments for personal staff, transport, telephones, accommodations, vehicle permits, etc. can be drastically cut down.

The total of 250 elected members compared to the current total of 680 (225 Parliament members and 455 provincial council members) is more than a 60% reduction in the total number of MPS and MPCs in the country. However, the current provincial council physical infrastructure, administrative layer and other resources will be required to exercise the powers vested to the provinces through the 13th Amendment.

Mixed electoral system

The national election can be held based on a 65% to 35% mixed electoral system to elect electoral members based on the first-past-the-post (FPTP) method and Proportional Representation (PR). Single vote marking for a constituency’s candidate is more appropriate to avoid complexity. The vote marked for the candidate is also counted for the candidate’s party or group in the district proportional vote calculations.

160 FPTP seats

160 electoral members can be elected based on the FPTP method for 160 (Section 98) existing electoral constituencies.

90 PR seats

A further total of 90 electoral members based on PR is proposed to be elected for nine provinces (22 electoral districts). Members are elected based on the district proportional votes received by the contesting political party or independent group. Respective provincial councils can be formed by combining the elected members of relevant districts.

Accordingly, approximately 65% of electoral members (160) are elected through the FPTP method and 35% (90) are elected based on the PR method.

Replace preferential voting with District Proportional List

District-based preferential voting can be abolished by introducing a District Proportional List (similar to the existing National List).

The District Proportional List can be submitted by each contesting political party or independent group prior to the national election. The District Proportional List has to be prioritised on the name order decided by the contesting political party or independent group at the time of submitting nominations. District proportional vote-based electoral members are elected as per the name order submitted by each party or the ‘Closed List’ method.

District quotas for proportional representation

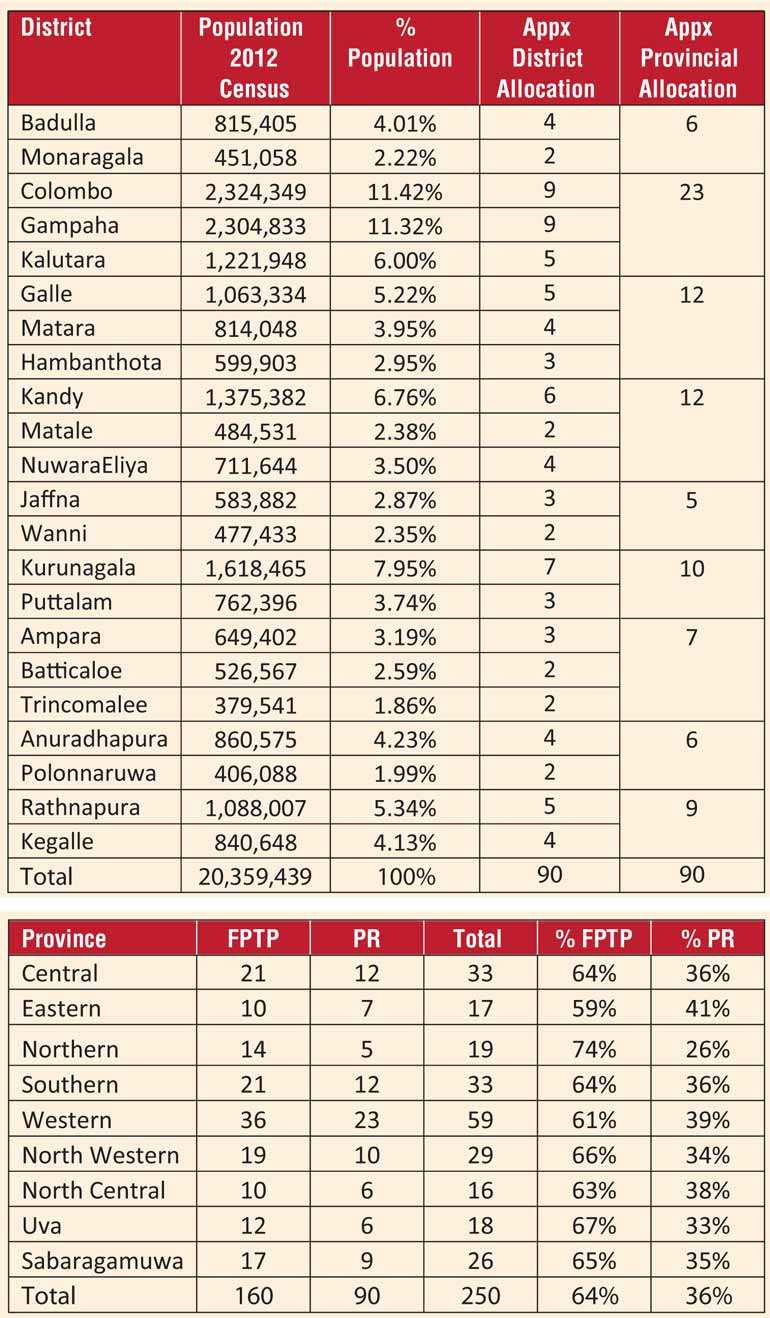

The distribution of 90 seats among the 22 electoral districts (hence nine provinces) can be decided considering the population and geographical extent of each province or based on a similar suitable formula.

An example of the proposed district proportional seat quota based on population (or perhaps on registered voters) is listed below. The district quotas given below are proposed only to demonstrate a methodology and a more accurate and fairer formula could be developed through further deliberations.

Election of district proportional vote-based members

Elected member allocations for proportional votes received by each political party or independent group in a district can be decided based on the district proportional votes received by each party. An established formula used in other mixed electoral system democracies can be used to calculate the ‘Relevant Number’ and ‘Resulting Number’ (Article 99, 14th Amendment) for the allocation of each district’s elected members.

The National List

The National List was intended to elect members based on the national proportional votes received by each party. Based on the proposed format, a total of 90 electoral members were elected based on proportional votes.

The National List also accommodated experts and specialists from various nationally important disciplines to contribute their services to the Legislature. They too can be accommodated on the District Proportional List (DPL). Hence, the existing 29 National List seats based on Section 99 (A) can be abolished. However, if the National List has to be accommodated for the further benefit of minor parties, a list of 20 National List MPs can be accommodated by reducing the number of district propositional representation-based elected members to 70.

Composition of provincial councils

A tally of 250 electoral members elected through the National Election will perform the duties and functions of respective provincial councils vested under the 13th Amendment as elected members of those provincial councils.

An example of the distribution of the 250 elected representatives to all provincial councils and the Parliament is provided below. Accordingly, approximately 65% of electoral members (160) are elected through the FPTP method and 35% (90) are elected based on the PR method.

As per the table, a 65% FPTP to 35% PR ratio can be roughly maintained at the provincial level too. The allocations and methodology presented are to establish the concept. Final allocations and minor anomalies (e.g. Northern Province and Western Province) can be rectified and perfected through further deliberations by experts.

Number of ministers can be limited by the Constitution

The number of national ministries and provincial ministries can be limited through the Constitution as already enacted through the 13th Amendment. More meaningful figures for such limitations are 25 national ministers and five provincial ministers, including the chief minister for each province. Since 45 provincial ministers could shoulder the bulk of the policy implementation burden of devolved subjects, there would not be a great necessity to appoint deputy or junior ministers at the national level. If junior ministers are to be appointed due to the ruling party’s internal compulsions, the total number of national ministers and junior minister could still be limited to 25 portfolios to handle powers not devolved to the provinces. This measure too would save a considerable portion of Government expenditure.

Cross overs

It is shameful to watch the ugly cross over dramas during vital elections and it is imperative to rectify the situation through constitutional moves. It is proposed to elect new electoral member through an electoral by-election or from district proportional “Closed List”, when an electoral member is lawfully removed by the party as result of a cross over.

Risk of a defunct legislature

In the event a whole provincial council or a group of electoral members boycott or do not exercise national legislative duties, there is a risk of national legislature becoming defunct. Such risks can be averted by vesting necessary powers with the provincial governor, the parliament and the president in ascending order to dissolve and call for provincial by- elections or electoral by- elections.

Reforms strengthens power decentralization as well as unitary character of the state

With the proposed convergence, provincial councilors are further empowered with broader political power. But as they are participating in the national legislative function ,the unitary character of the state is safeguarded. This is a unique advantage of the proposed solution.

Duty of the Next President

Once elected , the new President will be the head of state of all citizens. His responsibility is to hold the nation together irrespective who voted whom and lead the reforms agenda to achieve peace and prosperity for the country.

The salient feature of the current constitution is that no government under 1978 constitution got absolute majority other than in 1989 and 2010 general elections. As a result , governments are becoming weaker and weaker. Smaller parties hold governments to ransom with demands that are entirely politically motivated. Many a time this has become a hindrance to progressive policy making by successive governments.

Hence meaningful constitutional reforms are urgent. However constitutional reforms need two third majority in the parliament. This can be only achieved by inviting a group of progressive opposition members to support the urgent constitutional reforms and provide necessary two third majority. Once elected , we look up to the new President to use his mandate by the people to bring key political forces and entire nation together to lead constitutional reforms necessary to rectify the key weakness in the status quo. The objective of the above outlined formula is to emphasize the need for an out of the box solution and trigger a discourse for progressive constitutional reforms.

The writer a is an Engineer by Profession. He holds a BSc Engineering Degree from University of Moratuwa and MBA from University of Hull UK. He can be contacted at [email protected].