Monday Mar 02, 2026

Monday Mar 02, 2026

Monday, 14 September 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Moving forward, Sri Lanka should prioritise policy measures to support recovery in maritime trade

Introduction

The oceans, particularly maritime trade, have been the lifeblood of the modern global economy from the mid-20th century to the early 21st century. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the outlook for global maritime trade and the global economy. However, uncertainties remain on when global maritime trade might recover and what it means for Sri Lanka’s maritime industry.

The role of maritime trade in the global economy

There are different ways to study the oceans economy. The blue economy concept is popular in research studies but often lacks detailed data at the national level. Maritime transport – represented by the volume of container traffic – is a convenient way to empirically dissect the dynamics of the global maritime economy. From the mid-20th century to the early 21st century, maritime transport grew exponentially as changes in international trade, seaborne trade, and technology became interrelated.

The key game changers include the advent of container shipping where cargo ships carry their load in truck-sized 20-foot containers, the introduction of megaships, automation, alternative fuels, and development of world class ports. Maritime shipping is one of the most globalised industries in terms of ownership and operations.

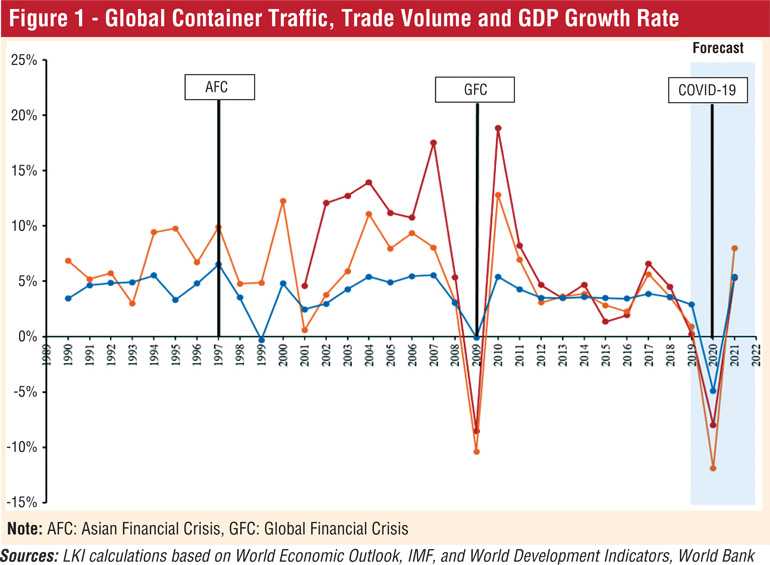

Global container traffic – in terms of twenty-foot equivalent units or TEUs – grew at some 12% per year during the heyday of globalisation in the 1990s and early 2000s to reach a capacity of 516 million TEUs in 2008. Much of this growth is due to dynamic East Asia and the Pacific, which made up half of global container shipping capacity (2008). Meanwhile, North America made up 19%, Europe for 8%, and the rest of the world (ROW) 20.6%. Powered by maritime trade, which accounts for 80% of global trade volume, the global economy grew at a healthy 4.3% per year (1990-2007).

The impact of COVID-19 on global maritime trade

According to LKI forecasts, calculated using IMF data and other sources, global container traffic is likely to fall by about -8% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The decline was especially marked in East Asia and the Pacific, while it was notable in North America and Europe. An uptick in global container traffic is expected at about 5.3% in 2021. . Global container traffic could recover from 731 million TEUs in 2020 to 770 million TEUs in 2021. This scenario could translate into the IMF’s projection of global GDP growth of -4.9% in 2020 and 5.4% in 2021.

Comparing the COVID-19 shock shown in Figure 1, with the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (GFC) shows a slightly larger fall in global container traffic (-8.5% in 2009) and a similar rebound in global GDP growth (5.4% in 2009). However, the post-GFC recovery in container traffic was not sustained in subsequent years. Instead, there was tepid global maritime growth (3.3% p.a. in 2013-2019) and GDP grew slowly (3.5% p.a. 2013-2019). Coming back to the post-COVID scenario, the global recovery in 2021 and beyond would depend on the duration of the pandemic and the effectiveness of the policy response.

Other downside risks also cloud the global maritime trade horizon. High debt levels of container carriers create insolvency risks for the shipping industry. The OECD estimates that cumulated debt of 14 major container carriers reached $ 95 billion by the third quarter of 2019. In addition, heighted trade and technology tensions between the US and China (and talk of economic decoupling) would hit global value chains (GVCs) centred on China and maritime trade. Finally, rising geopolitical and cybersecurity risks may also affect maritime trade.

In summary, LKI’s post-COVID scenario could indicate a bathtub shaped U period ahead for global maritime trade rather than a sharp and sustained V shaped recovery.

Implications for Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is strategically located in the centre of the Indian Ocean, roughly 10 nautical miles off the traditional East-West maritime trade route. The region sees some 60,000 ships passing through annually. In 2018, Sri Lanka accounted for 24% of container traffic in the South Asian region and typically grew faster (YoY) than the regional average. Much of this success is attributed to the performance of Colombo Port. Ranking 24th on the Lloyds List in 2019, Colombo Port is a small but a significant player in the region, acting as a major transhipment hub connecting to India and other countries.

The initial impact of the pandemic was a substantial fall in international trade, owing to demand and supply shocks. Being a key trading hub in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka experienced a fall in cargo volumes. According to the Department of Customs, 1,200 full container loads of import and around 525 containers of exports were cleared on a daily basis before the COVID crisis. These numbers have dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic to 524 containers of imports and 220 containers of exports – a 24% decline overall.

The export shock experienced earlier in 2020 was quite significant. Sri Lanka’s merchandise exports dropped 42% to $ 645 million in March 2020, with apparels falling 41% to $ 531 million and tea falling 50% to $ 62.5 million. This downturn continued in April, with merchandise exports falling further by 65% to $ 277.4 million. The magnitude of the shock was a result of dampened demand, as Sri Lanka’s key trading partners around the world imposed strict curfews and lockdowns. As well as a contraction in supply as local industries scaled back production due to import controls and lack of raw materials.

Broad import restrictions were imposed as early as March 2020 to address the foreign exchange crisis resulting from the pandemic. As such, imports to the country have been in a steady decline. Similarly, transhipment throughput in Colombo fell to 375,241 TEUs in April from 501,478 TEUs in March as neighbouring countries such as India and Bangladesh went into strict lockdown and border closure. Coupled with blank (cancelled) sailings by prominent carriers, the extent of the impact on Sri Lanka’s transhipment trade has worsened.

More recently, however, there are signs of a modest up-turn in Sri Lanka’s maritime trade. The Department of Customs has noted a slight rebound in cargo volumes, which are roughly doubling daily in August. New services which were introduced during the lockdown period helped Colombo Port remain functional but has also supported this upturn. For instance, paperless processes were integrated into many of the port-related services. Segments of the cargo clearing process and terminal operations were digitised and streamlined in order to ensure continued operations. The beaucratic procedure of submitting paper documents (such as the certificate of origin for certain products) in person, were also temporarily removed.

Exports rebounded sharply reaching $ 1 billion in July, after plunging to $ 250 million in April. This was mainly driven by the increase in demand for locally produced PPE equipment such as face masks, gloves, and other protective equipment. Export earnings from tea has also increased by 18% (YoY), due to changing consumption patterns and increased demand from Turkey and Russia. Transhipment volumes also recovered slightly, to 407,139 TEUs in May and to 452,131 TEUs in June. Volumes seem on route to pre-COVID levels, Sri Lanka used to process close to 450,000 to 500,000 containers of transhipment per month on average.

Moving forward, Sri Lanka should prioritise policy measures to support recovery in maritime trade. A couple of measures might be mentioned here. As the volume of cargo is rising, the safety and security of port workers should be carefully calibrated into calculations of port efficiency and competitiveness. The health of such essential workers, will play an important role in the recovery period and determine how efficiently the port operates. To aid this process, projects related to greater digitisation of port operations, promoting automation, and cutting of red tape pertaining to international trade should be implemented.

In order to mitigate port capacity constraints at Colombo Port, planned port developments including the delayed East Terminal project should be speeded up. A private sector-oriented solution like forming a public-private-partnership, through a competitive tendering basis with a multilateral development bank playing an honest broker role could be one way to approach this issue. Whatever solution is ultimately adopted, the best possible financial terms for Sri Lanka should be ensured as Colombo Port is a strategic national asset while considering the sensitivities of the neighbourhood.

Seen in purely commercial terms, Sri Lanka’s transhipment trade is heavily dependent on the Indian market and such trade seems at risk. Geopolitical concerns in Indian policy circles have prompted investment to upgrade major Indian ports through the Sagarmala Initiative and a planned transhipment port in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Policy response

More generally, a coordinated response at the global, national, and industry levels is needed to build the foundations for a recovery in global maritime trade.

At the global level, quiet diplomacy, and cooperation can help to address trade tensions and rising protectionism, maritime crime, and geopolitical risks. Coordination is also needed to tackle industry-specific issues. E.g. ensure better safety and security at sea, re-look at IMO 2020 environmental regulations, and enforcement of the Law of the Sea.

At the national level, countries should keep ports open (through, for e.g., staggered working hours and implementing health measures to minimise interference with carriers), invest in port modernisation, upgrade to world class customs/trade facilitation systems, and better link into global shipping networks. Stimulus packages are also critical to support demand, maritime industry restructuring, and social safety nets for displaced seafarers

At the industry-level, container carriers should adopt more resilient business models with risk management, debt restructuring, with a special focus on health services to seafarers. Excess capacity in carriers may need addressing through reducing ship speeds, scaping old ships, and cancelling orders new ship orders.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely impacted global maritime trade and the world economy. Global container traffic is estimated to contract in 2020, as world GDP and trade volumes have declined severely. Looking at the GFC experience and other indicators points to a recovery in global container traffic in 2021. Whether this is sustained or not depends on influence of various risks which cloud the global maritime outlook. A coordinated response at global, national, and industry levels is needed to set the foundations for a recovery in global maritime trade. Sri Lanka, being a strategic trading nation, should also push forth key policy measures which will not only aid the recovery process, but also address the growing maritime competition in the region.

(Ganeshan Wignaraja is the Executive Director at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. Pabasara Kannangara is a Research Associate at LKI. The opinions expressed in this piece are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.)