Monday Mar 09, 2026

Monday Mar 09, 2026

Friday, 31 July 2020 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics’. All issues are political issues....”

George Orwell – Why I Write

At a time of tumultuous turmoil Rauf Hakeem has authored a book. It is a profoundly poignant produce by a politician. He has addressed the next generation. That earnestness must be celebrated.

I read plenty of books. It is not often that I am asked to review a book.

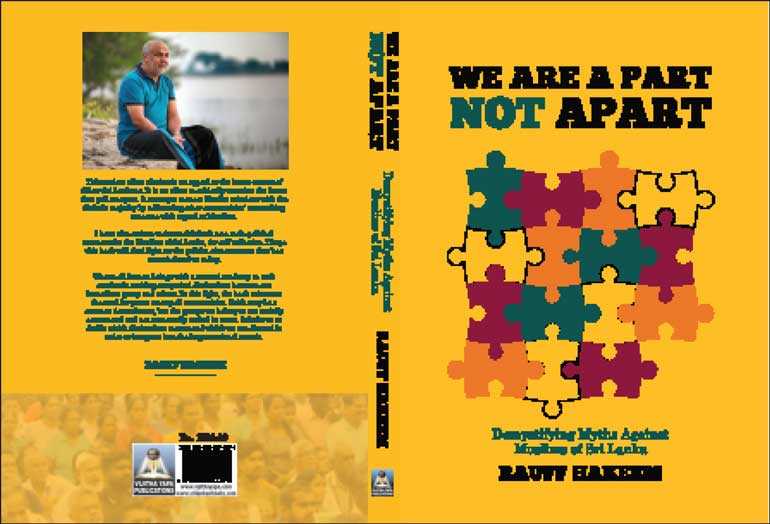

I was pleasantly surprised when I received Rauf Hakeem’s new book from Vijitha Yapa the publisher, with the terse business-like one liner enclosed a copy of the book ‘We Are A part, Not Apart’ for a review.

A jigsaw puzzle of multihued interlocking pieces adorns the cover. The strap line below the graphic depiction is a succinct statement of its contents – Demystifying Myths Against Muslims of Sri Lanka.

The book overall keeps to its undertaking although demystifying myth is easier said than done. Ours is Ravana land. Poor Rauf Hakeem has a tough task. He emerges reasonably unscathed.

I took serious note of the book. The title ‘We are a part not apart’ is both a cry of anguish and a courageous affirmation. The strap line is an explicit demarcation of a contemporary predicament.

The book is dedicated to the author’s loving daughters and their multicultural friends. I take a father who dedicates his book to his two daughters and their multi-cultural friends very seriously. Fathers do not offer daughters and their fiends their distilled wisdom lightly.

Chapter one explains how the Muslims of Sri Lanka fit in to the nation’s multihued mosaic. “A foundational fallacy that needs to be challenged is that Islam is an Arabic tribal monotheism”. Brought to this island by the Monsoon winds of the Indian Ocean, they are a community whose destiny is to adjust their sails to the prevailing winds. They must sail in solidarity or be shipwrecked in isolation.”

There are five chapters. Chapter 2 is a serious scholarly approach that debunks perceived fears of Muslim demographic amplification.

Chapter 3 offers a cogent exposition of Muslim cultural and social norms. Hakeem is honest about what is archaic among Muslims and brave in accommodating modernity’s inroads.

Chapter 4 deals with ethno religious extremism. A brief extract would demonstrate the charming courage of a politician representing a minority community trapped in the oxymoronic impasse of retaining idealistic consistency and paying the price of pragmatic leadership. He asks, “Is multicultural democracy an abstract concept or a lived experience?”

I will not go into the last chapter 5 – Towards a common future for all.

It is a book about being and doing. What I found most attractive is that despite being neck deep in competitive party politics, he has studiously avoided being self-congratulatory or defensive.

He has dealt with a serious subject in unsettled times of great turmoil. He has kept faith with his two daughters and their generation.

A pragmatic leader is focused on how to get things done. The idealistic leader is focused on a vision. The book depicts a man capable of managing the chemistry of idealistic allegiance and pragmatic rationale.

Hakeem is reconciled to the imperfections we must live with. But imperfections can be made less imperfect.

His ‘critical pluralism’ is an imaginative construct. The book is a good read for the politically curious and socially solicitous.