Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 18 February 2019 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Many are of the opinion that unless conscious efforts are made, inter-ethnic conflicts of the past may recur or perpetuate as inter-ethnic tensions and pose fresh challenges to national harmony and social integrity – Molly Mueller, Asia Foundation

In an article titled ‘Sri Lanka Launches Plan to Become Trilingual Nation’ appearing in the Asia Foundation website(https://asiafoundation.org/2012/03/28/sri-lanka-launches-plan-to-become-trilingual-nation/), on 28 March 2012, Molly Mueller stated Sri Lanka is a multilingual, multiethnic and multicultural country striving to maintain its diversity and yearning to forge a national identity transcending its differences.

“The two major linguistic communities – Tamil and Sinhala – maintain their languages for in-group communication and also use them for official purposes in their territories. Both languages are regarded as National Languages and the two communities equally value their mother tongue as the key to social identity, as an instrument par excellence for cultural expression, and as the most authentic resource for preservation of traditional knowledge, values and wisdom. They fully endorse the primacy given to their languages in the education policy.

“English, a shared legacy of the colonial past, is valued in contemporary society as a life skill, as an inevitable resource for modernisation and upward social mobility, and also essential for gaining access to specialised information and content not yet available in their own languages. English is considered necessary for quality education with a general consensus to provide early access to it at the primary level itself and the present policy caters to these aspirations

“Recognition of both Tamil – a Dravidian language – and Sinhala – an Indo Aryan language – as National Languages may have enhanced and equated their symbolic status, but in the absence of language planning for bilingualism, the two communities have been allowed to grow in segregated fashion, and communication problems have not only survived but have grown in complex ways to affect both social and political spheres. Many are of the opinion that unless conscious efforts are made, inter-ethnic conflicts of the past may recur or perpetuate as inter-ethnic tensions and pose fresh challenges to national harmony and social integrity.”

Official Languages Policy

According to the Official Languages Policy of Sri Lanka, a person is entitled to be educated through the medium of either of the National Languages; recently, English has re-joined Sinhala and Tamil languages as a medium of education; both Sinhala and Tamil are the languages of administration throughout Sri Lanka; the maintenance of public records and the transaction of business in public institutions are done in Sinhala in all the provinces of Sri Lanka other than the Northern and Eastern Provinces where Tamil shall be used; however, the Sinhala or Tamil linguistic minorities of the Northern and Eastern Provinces, or of all the other Provinces respectively are enabled to have their business attended to through the medium of their own native language, or another language of their choice; the language of legislation and that of the courts, too, are both Sinhala and Tamil; all laws and subordinate legislation are enacted or made and published in Sinhala and Tamil, together with a translation in English. When citizens feel that their language-related rights are being violated, there is provision for legal redress.

Eight years ago, a 10-year master plan was launched for a trilingual Sri Lanka. The Government of the day also could claim credit for initiatives such as the One thousand Mahindyoda centres of technical excellence, the LLRC report and the action plan, the report and the recommendations contained in the Paranagama Commission of enquiry on Missing Persons. The Mahinda Chinthana plan itself was a useful document that provided the citizens of Sri Lanka a pathway to the future for the country as envisioned by that regime.

These initiatives are mentioned not with a view to holding a candle to the then regime, but to record an appreciation for some visionary initiatives of the Government which would have helped Sri Lanka to move from the aftermath of a debilitating war to a new future as Sri Lankans.

A trilingual Sri Lanka

In respect of a trilingual Sri Lanka, the LLRC report recognised its fundamental importance as a pathway to long term reconciliation amongst the Sinhalese and the Tamils and all other communities in the country. It deal extensively with this – See ‘Promoting trilingual education at school,’ http://www.moe.gov.lk/llrc/index.php/promoting-trilingual-education-at-school.

Rohana Wasala writing in a national newspaper on 2 December 2010, under the title ‘The Ten-Year Master Plan for a Trilingual Sri Lanka,’ http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=12570) said: The 10-year National Master Plan for a Trilingual Sri Lanka (2011-2020) to be launched as a presidential initiative is going to be a massive implementation-oriented language management exercise, probably the most ambitious ever of its kind. A survey carried out by an independent research organisation for the Public Survey and Research Unit of the Presidential Secretariat has revealed a clear perception among Sri Lanka’s major ethnic communities of the desirability of a three language system for strengthening national harmony. This is a good trend that should be encouraged and exploited, for the success of any language planning enterprise will ultimately depend on its acceptance by the people.”

Sajit Prematunga writing in a national newspaper of 23 June 2011 on ‘The Ten-Year National Action Plan for a Trilingual Sri Lanka: Redefining language’ (http://www.dailynews.lk/2011/06/23/fea01.asp), had this to say about the 10-year plan: “Nearly 90% of Sinhala speaking people cannot communicate in Tamil and cannot communicate effectively in English. Whereas 70% of Tamil speaking people in Sri Lanka cannot communicate in Sinhala. But the new Presidential initiative on a trilingual Sri Lanka plans to change this. A salient feature of the Presidential initiative for a trilingual Sri Lanka is the redefinition of language. ‘The initiative will not promote Sinhala and Tamil as mere instruments of communication, but as a holistic cultural package,’ said Presidential Advisor and Coordinator of the program ‘English as a Life Skill’ and the initiative for a trilingual Sri Lanka, Sunimal Fernando. ‘Language is an expression of culture. Knowledge of Tamil culture will facilitate empathy and affection for its culture in the Sinhala people and thereby encourage people to learn the Tamil language. The same goes for Sinhala.’”

Good initiatives abandoned

To the best of this writer’s knowledge, Sri Lanka has not had any kind of plan for trilingualism either before or since the launch of that plan in 2011. Unfortunately, with the change of government in January 2015 that plan, as well as the other reports and plans noted above, have not been actioned by the succeeding government perhaps simply because they were the initiatives of the Rajapaksa regime.

Any objective-minded person would have realised the value of these initiatives and had they been even remotely visionary, would have improved on these if they thought they needed improvement, and would have carried on the implementation. Even President Sirisena who was intimately associated with these useful initiatives as a senior cabinet minister in the Rajapaksa regime, has been silent about these initiatives and neither he nor the Government of Prime Minister Wickremesinghe has come up with viable alternatives in place of these initiatives.

Vision and an action plan

The focus of this article is the ‘Trilingual Sri Lanka’ vision. This vision is vital to the future of the country as without the ability to communicate with each other in Sri Lanka and with the rest of the English-speaking world, we would continue to remain as frogs in a pond. However, a vision alone is not sufficient and there in a need for an action plan (if the previous plan is not good enough for this Government) to make this vision a reality.

It is known that trilingualism has been introduced in schools although it is not clear whether this has been done across the board throughout all schools in the country. The writer is personally aware of some schools where this policy has not been introduced, and it is for no fault of the schools. It is due to a simple reason. It is because there are no teachers to teach language whether it is the written language or the spoken language or both.

The difficulty in finding teachers is a monumental task as we have not had a concerted effort to implement trilingualism till 2012 and we have not had a plan to identify teacher requirements, and equip them to teach the three languages.

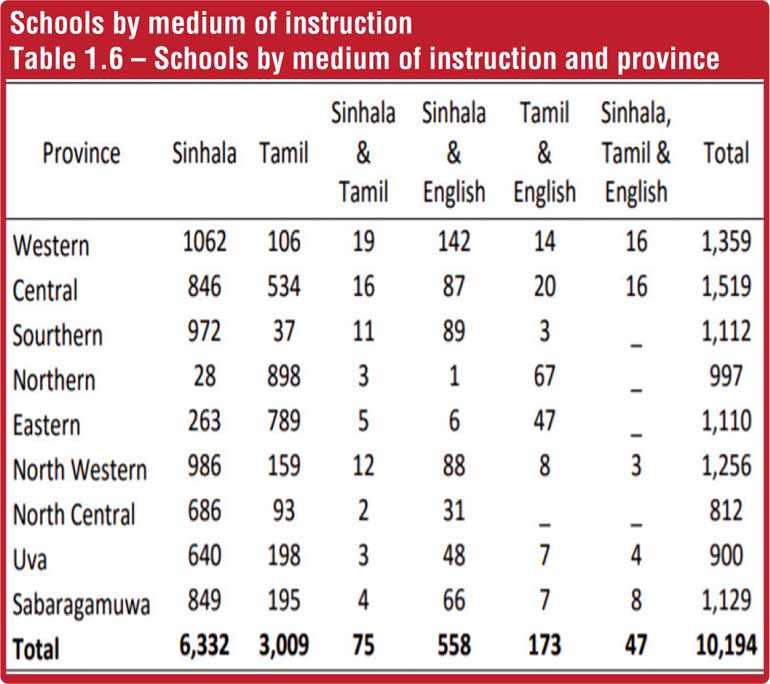

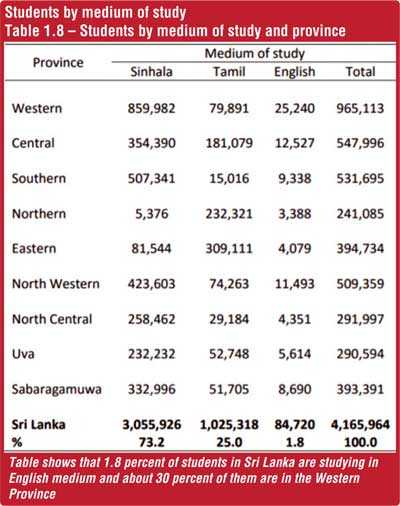

The tables below (1.6) extracted from the Sri Lankan Department of Education School Census Report 2017 does not show the number of schools where all three languages are taught and not necessarily where the medium of instruction is available in all three languages. If trilingualism for the education ministry is the latter then, then trilingualism has a very long way to go.

The table 1.8 shows that language of study is still in the proportion of the Sinhala and Tamil population demographics in the country with perhaps some Muslim students studying in Tamil.

Table 1 shows that language of study is still in the proportion of the Sinhala and Tamil population demographics in the country with perhaps some Muslim students studying in Tamil.

In schools, the compartmentalisation by the two languages Sinhala and Tamil is evident even as of 2017.

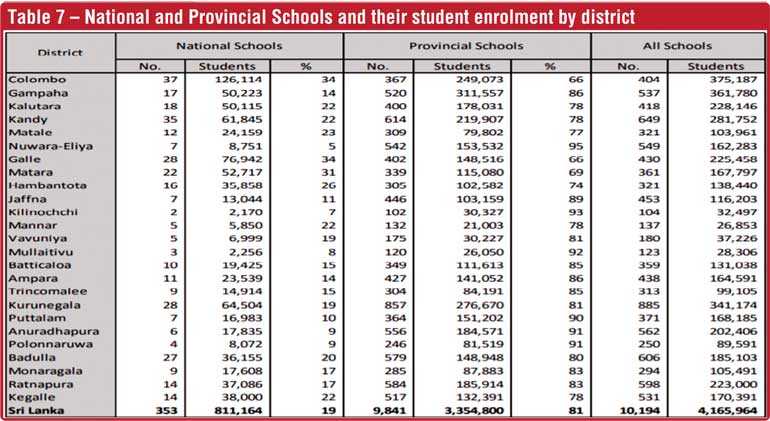

One of the huge challenges for the Ministry of Education would be to find teachers who at least have minimum competencies to teach the three languages. With over 10,000 public schools in the country this cannot be an easy task.

However, if trilingual Sri Lanka is to become a reality, there will have to be such teachers who could be deployed to all the public schools in the country. This too cannot be done in a short period of time and this is where a long term plan to develop such a competency amongst teachers is necessary.

Tech to the fore

The country has other choices as well. This is to make use of technology that is available today to undertake online teaching of the three languages. The Mahindyodaya concept was about setting up of 1,000 technology excellence centres for students above a certain grade. Considering that Sri Lanka has a good Wi-Fi coverage in most parts of the country, language laboratories could be set up progressively in all schools so that teaching could be done online either through a national centre or provincial centres. A school could have a minimum of one such laboratory with a computer and a multimedia and an internet connection.

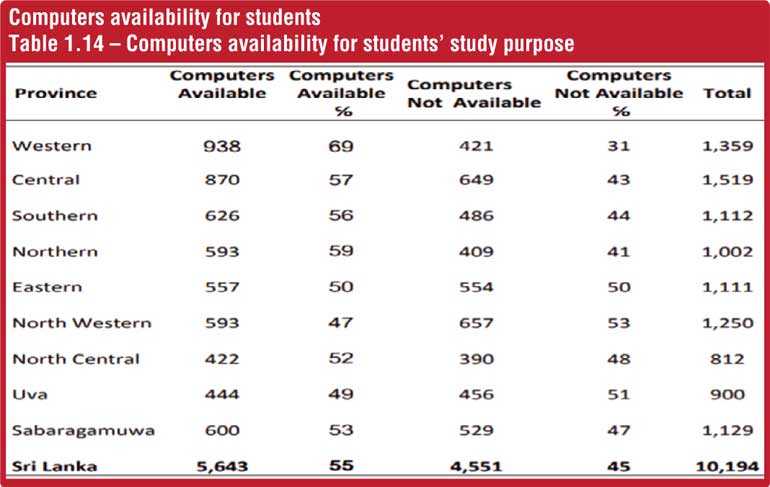

According to statistics in the 2017 education census report, 55% of Sri Lankan public schools numbering 10194 have computers while 45% do not. In theory, an online training program could commence in 55% of the schools provided they have Multi Media and an internet connection.

While statistics on computer availability by type of school, i.e. whether they are national schools or provincial schools is not available, it is more likely that all national schools would have computers and also access to the internet. If this were the case, online teaching could commence in all national schools in the first instance, and progressively be introduce to all provincial schools.

Teaching methods in many parts of the world, in developed as well as in developing countries are now based on a mix of face to face teaching and technology oriented methods such as online and offline (as an example, lectures and notes are provided in soft form and students are not compulsorily expected to attend lectures for some subjects) teaching.

Wi-Fi in teaching

Sri Lanka is yet to capitalise on the advent of Wi-Fi in teaching. As it is fairly common practice in Sri Lanka, everyone is waiting for the Government to take the initiative with regard to innovations in teaching methodologies. Why not the private sector? Why couldn’t the Wi-Fi providers in Sri Lanka form a consortium and provide Wi-Fi access to every nook and corner of the country? Why couldn’t they also invest in providing computers and multi-media to schools who don’t have them and work with provincial education authorities to set up at least one teaching laboratory in every school in the country? The return on their investment will be very quick for the consortium members when more and more schools commence using Wi-Fi for teaching.

From all accounts it appears that since independence, Sri Lankan politicians have achieved very little in promoting and implementing a language policy that could unite its citizens and overcome its divisions while enjoying the pleasures of a diverse population and its cultural practices. The non-government sector too has not helped as much as they could have.

Sri Lanka’s cultural diversity is as rich or richer than its natural beauty. The inherent kindness of its people fashioned by its many religions and cultures is something that many other countries that do not have Sri Lanka’s diversity would die for. Sadly, Sri Lankans have from time to time killed each other trying to wreck this diversity. As a consequence, they have become poorer as a society by running back to its silos and not seeing the beauty that is around then.

It is time all political leaders and the leaders of our civil society sat down to work out a national plan to make Sri Lanka a trilingual nation where its diversity is recognised as its greatest asset.