Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 21 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

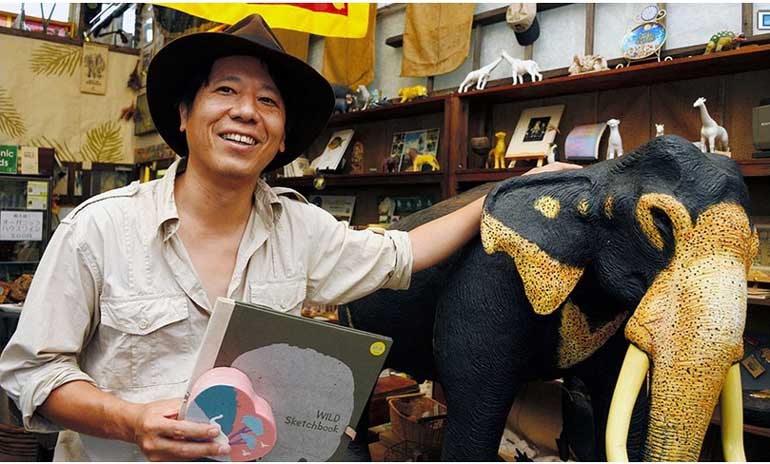

Hisashi Ueda sells paper made with elephant dung at his shop in Kita-Hiroshima, Hiroshima Prefecture.

Hisashi Ueda sells paper made with elephant dung at his shop in Kita-Hiroshima, Hiroshima Prefecture.

(Asahi Shimbun) After dabbling in Sri Lanka?s plastic, tea and gem markets, Hisashi Ueda struck gold using a more down-to-earth resource: elephant dung. His company, Michi Corp., began selling paper made with recycled pachyderm poo in 2002.

His company, Michi Corp., began selling paper made with recycled pachyderm poo in 2002. The Sri Lankan-produced “Elephant Paper” is now exported to more than 10 countries and has become a popular souvenir item at Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo and 70 other venues in Japan.

The paper feels somewhat rough and features irregular patterns of plant fibers.

Ueda’s link to the island nation in the Indian Ocean started with a chance meeting in the late 1990s.

One day, a Sri Lankan stranger asked Ueda for money at a train station in Tokyo. The man, a government official, was visiting the capital to solicit cooperation from Japanese companies for a planned technological training program for Sri Lankans.

Ueda gave him 10,000 yen ($84). The Sri Lankan was enormously grateful.

Back then, Ueda, a native of Gifu Prefecture in central Japan, exported second-hand industrial-use printing machines to other Asian countries. His Tokyo-based business was doing well, but day after day of routine work made him feel like he had reached a dead end.

He was looking for an eye-opening experience.

That opportunity came about in 2000, when the Sri Lankan invited Ueda to his wedding.

When Ueda, 44, visited Sri Lanka for the nuptials, he realized that mountains of garbage, a byproduct of the nation’s rapid urbanization, had become a serious problem.

Plastic bottles were mixed with all sorts of trash because separating recyclables from non-recyclables had not been rigorously enforced.

Ueda started a business of recycling plastic bottles in Sri Lanka, but he gave up after the endeavor proved economically infeasible.

He stayed in the country, living off his savings, and turned to trade in Sri Lanka’s famed tea and jewels.

One day, he learned about a local entrepreneur’s experiment in making paper with elephant droppings. He found the idea “amusing.” He also saw a business opportunity. Elephants are voracious eaters, and their droppings contain a high degree of plant fiber. Ueda set up a paper-manufacturing factory near the Elephant Orphanage on the outskirts of Kegalle. He also drew upon a technique used to produce traditional Japanese “washi” paper.

Factory employees collect the elephant feces at the orphanage. They dry and boil the droppings for a day for sterilization before blending them with used paper from local printing companies.

Workers thin out the mixture into sheets by hand and dry them under the sun.

The factory produces thousands of sheets a day.

The Elephant Paper has also reshaped the locals’ view of the species as a “troublemaker” that wreaks havoc on farmland into “the animal that makes money,” according to Ueda.

Ueda does not limit himself to just one line of business.

After the confusion that followed the Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster in 2011, he became interested in developing a self-sufficient lifestyle.

He moved his base from Tokyo to Kita-Hiroshima, a mountainous town of 20,000 in Hiroshima Prefecture. He became involved in whatever interested him, from running a caf? and a publishing company to fishing.

Always ambitious, Ueda’s to-do list for the coming years includes producing space food to sell to NASA.

“I have experienced the thrill of taking on something interesting in Sri Lanka,” he said. “I want to have an exciting life.”