Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 28 August 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Hemal de Silva

By Hemal de Silva

The series of ‘Lost crops of Africa’ was published by the US National Academy of Sciences and Vol. 3 on fruits was published in 2008. Consulting Author and Scientific Editor Dr. Noel Vietmeyer explains in the foreword that these fruits described are indigenous species of African origin, multipurpose assets for relieving or reducing problems such as hunger, malnutrition, rural poverty, devastation from unsustainable land practices, fearsome diseases and their often added burdens for women, mothers and children across the vast and troubled landmass lying below the Sahara.

They are not literally ‘lost’ but forgotten or overlooked despite having been known to and fed the rural populations without receiving adequate scientific investigations and development to fully benefit from their inherent potential. Fruit trees are known to hold fragile lands together, combating such encroaching calamities as deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution, desertification, urban blight and perhaps even climate change.

Continuing, Dr. Vietmeyer states that for such reasons African fruits deserve the scrutiny of science but most of all they need the esteem and support of those who are not scientifically trained. Surprisingly few of the premier fruits of the Western world were developed by scholars; most are the products of farmers, horticulturalists, and amateurs giving a good example. To quote, “For instance, the current ‘standard’ avocado (‘Hass’) was discovered by the children of a mail carrier who, in the 1920s, was starting a small grove in the hills outside Los Angeles, USA. Unable to afford trees that were already grafted, he planted seedlings of unknown pedigree as rootstock, and then grafted the then-dominate ‘Fuerte’ variety o nto them all. All the grafts took but on one seedling. He intended to chop it down but his children loved the flavour of its fruits so much he was persuaded to save it and, today, almost all of California’s avocado comes from that single rogue seedling of Mr. Hass.”

nto them all. All the grafts took but on one seedling. He intended to chop it down but his children loved the flavour of its fruits so much he was persuaded to save it and, today, almost all of California’s avocado comes from that single rogue seedling of Mr. Hass.”

Considering the clearly stated objectives of the study as explained by Dr. Vietmeyer, prompted me to inquire why the species, ‘Pentadesma butyracea’ had been omitted despite the known potential which was explained by me? Was I surprised to be informed that, to quote, “The plant certainly looks interesting and promising” and suggesting that I write it up under the above title!

‘Father’ of Pentadesma?

Investigating in the jungles of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire, Prof. Vijai Shukla, the President of the International Food Science Centre (www.ifsc.dk) based in Denmark, had come across an unknown fruit which turned out to be that of ‘P. butyracea S’, of the family Clusiaceae. He has carried out extensive research on the species and the potential of the vegetable oil/fat extracted from the seeds. I can only urge Prof. Shukla to find the time to publish his research for the benefit of humanity. Prof. Shukla is an Indian-Danish food scientist, researcher and professor in lipidology and a central figure in the study of essential fatty acids.

Geographic distribution

Pentadesma butyracea is found in the forests of Tropical West African Region (TWAR), from Guinea Bissau to Cameroon and western most DR Congo (www.prota4u.org). This species had been introduced to Seychelles where it has become ‘invasive’, Singapore and Sri Lanka over a century ago. In the 1960s, seeds had been taken from Africa and tried out in China, in the Yunnan and Fujian provinces where they have grown successfully and reported to be producing fruits satisfactorily.

The existence of two mature trees has also been reported in a National Park in Tanzania. Dalziel in The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa (1937) and Irvine in Woody Plants of Ghana (1961) describe this species. The species has so far not been established on a commercial scale. Probably the only small plantation that can be inspected is in Sri Lanka. It was established in November, 2009.

The interest in Africa

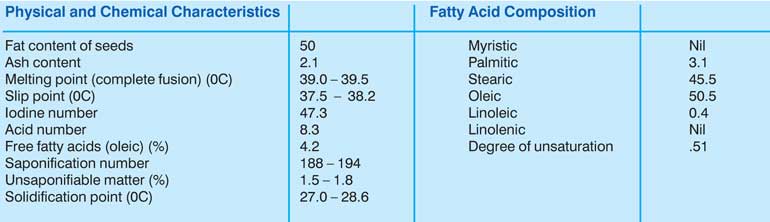

Dr. D. Adomako (Ghana) published in 1977 the specifications of the oil/fat in ‘Fatty acid composition and characteristics of Pentadesma butyracea fat extracted from Ghana seeds’. This information is given in table 1.

Dr. Adomako states that this species is well known in the Brong Ahafo region in Ghana and it will reach maturity in seven to eight years.

Since then, several Scientists in Benin, Prof B. Sinsin, C. Avocèvou, Dr. P. Tchobo, for instance have reported their research on the species and the oil/fat. Presently further research is being carried out to improve the efficiency of the extraction of the fat. In the TWAR, it is only in Benin that the exact locations where the species exists have been identified by Dr. A.N. Natta. Several Lipid Scientists in the EU have carried out research on this vegetable fat. Since 1977 it was known that Pentadesma fat is a substitute for cocoa butter. PROTA describes the species and some of its less important potential.

Why has there been no interest in any African country to start the establishment of this species begs for an answer. After being informed of the existence of thousands of Pentadesma trees in bearing, some greater than 100 years old in Seychelles, my brief proposal to the FAO, Rome received an immediate response with the offer to consider a grant of $ 300,000 within two years to organise the production of the fat.

In addition to the production in Benin, this is the only way to start the commercial production of Pentadesma fat right now by collecting all the fruits produced in the trees in bearing in Seychelles that are entirely wasted. The trees in bearing even if they are within the National parks will not be an impossible task to locate as they are all growing in small islands. The grant offered by the FAO was unfortunately refused by the relevant officials of Seychelles. This information was passed on to many in Benin, Burkina Faso, Togo, Ghana and Ivory Coast as these countries too could have obtained the same assistance to develop the production of the fat as a NTFP but, there appears to be no interest.

Why an interest in Sri Lanka for a ‘Lost Crop of Africa’?

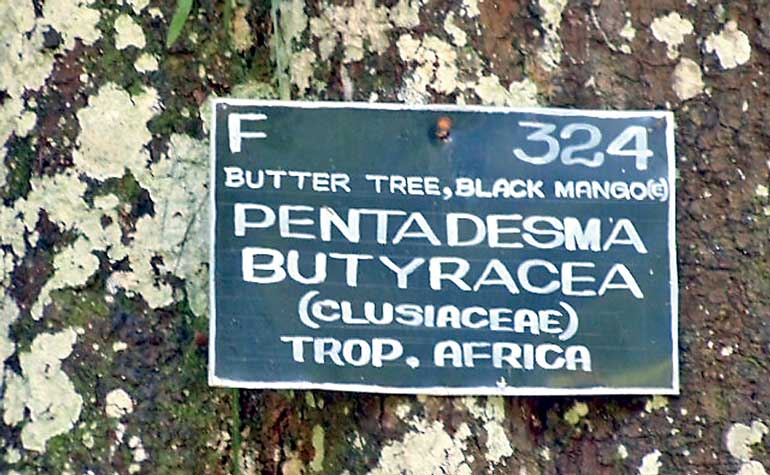

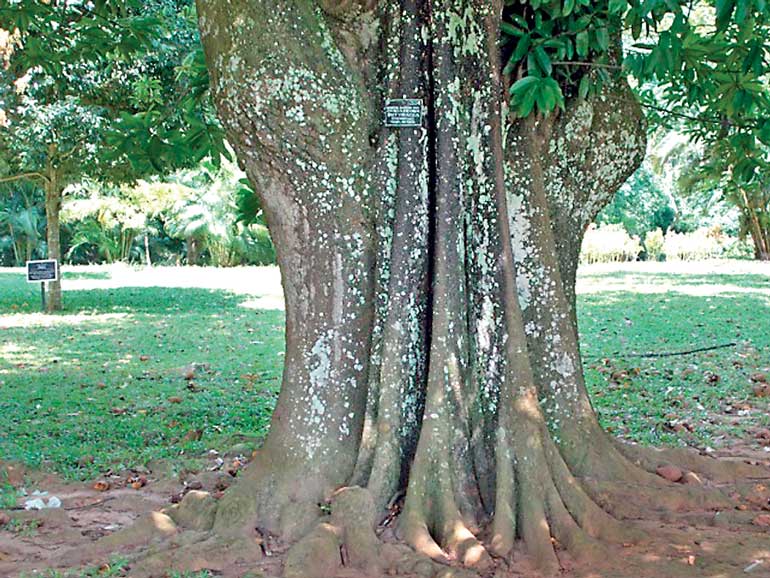

After all by 1987, there was just one tree at the National Botanical Garden (NBG), Peradeniya planted by an unknown benefactor in 1897.

Based on Prof. Shukla’s research, it was proposed to establish this species on a large scale in Sri Lanka starting about 1988. By a coincidence, I was an unofficial member of the team led by Prof. Shukla when they inspected the single tree at the NBG in 1987. I saw a big tree without any flowers or fruits on it. Subsequently, lands were inspected in Systems B and C in the Mahaweli Irrigation Project. At that time, lands for a large scale project to establish a perennial tree crop were only available in the dry zone, with or without irrigation.

118 year old Butter Tree in 2015 – Sri Lanka

Being aware of the climatic conditions in the dry zone and the necessity for adequate moisture for this species, I suggested to Prof. Shukla to consider taking on lease, app. 650 acres of abandoned rubber, in the possession of the Inland Revenue Department. My suggestion was accepted and the land was inspected by several involved with the project. Finally, a British planter was sent from Malaysia to inspect the estate in Matale. The inspection was of the slope and nothing else and he had reported the chosen estate not suitable for Pentadesma, a perennial tree crop.

If not for this baseless opinion, there would have been Pentadesma plantations of over twenty five years by now and very likely, a substantial extent under this tree crop in Sri Lanka. The trial project in several areas in systems B and C was not successful and the proposed project was given up after about one year.

I was unofficially involved with this proposed project for a very short period until my suggestion for establishment of the species in Matale was given up. Many others were involved with it from the inception until the pilot project was finally abandoned about two years later. Many Sri Lankan professionals would have learned the potential of the species and the final objectives of the project but, no one appears to have taken any interest in at least growing this tree crop on a small scale in Sri Lanka despite the availability of a substantial quantity of fruits and seed produced annually on the existing mature tree at the NBG!

20 years later, on 30 November 2007, remembering the particular tree I had seen in 1987 in the company of Prof. Shukla, prompted me to make inquiries about it. First of all, I had to find out its botanical name, which I was not aware of! Contacting the librarian at the NBG, it was given to me after sending a messenger to find it from the name board (picture below) fixed to the tree. From that day onwards, most of my many hundreds of inquiries by e-mail remained unanswered and unacknowledged but, the few replies received provided valuable information.

During the past almost eight years, like the proverbial tortoise I have kept moving forward slowly. I have been fortunate to find at least a good part of the potential of this species. By 2007, in addition to the big tree another two trees had been planted in the NBG about 1994.

118 years old tree (SL)

In 2008 at my request, our younger daughter brought back two fruits found fallen under the tree when she had visited the NBG. This was my first look at the Pentadesma fruit. I tasted the fruit and planted the four seeds. The fresh seeds germinated quickly. I obtained more fruits and raised 25 seedlings quite easily. This is the reason why it had become ‘Invasive’ in Seychelles. There was no necessity to plant the seeds as they germinated producing seedlings where the fruits decayed. In SL there was no organisation or individual willing to consider planting these seedlings. In 2009, the owner of a tea plantation expressed willingness to plant it on his estate and wanted seeds to be obtained for the purpose. When the seeds were ready for collection from the NBG, he backed out without a reason. Having placed the order for a few kilos of seeds,

I had no option but, to take it. It was quite a surprise when I went to the NBG to find 25 kg of seed waiting for me to bring back. I had no idea what to do with them but, I decided to purchase the seed and brought the lot by public transport on two occasions, cleaned and kept them moist to retain the viability. When each individual Regional Plantation Company (RPC) could have established this species on at least one ha of land, none showed any interest at all.

The many organisations involved with agricultural projects ignored the information offered to them. One and a half months later Roshan Rajadurai, former CEO of Kahawatta Plantations PLC decided, to my great relief to purchase the seeds. I handed over the best seeds and some that had already shown signs of germination, retaining the balance for drying. I had at least germinated and raised a few seedlings by then but, no one had even seen the seeds before.

One question asked from me by the Manager of the estate was how to place the seed for germination as rubber seeds are germinated keeping it in a particular way. My reply was to keep the seed in a moist seed bed and the shoot would grow upwards and the root would grow the other way. In fact this is how the seed germinate and grow. Subsequently, I learnt that Karunadasa, the Assistant on Hunuwala Estate, Kahawatta had raised the seedlings successfully and planted in the limited area despite not knowing anything about the species. When it was growing satisfactorily, he had taken a greater interest and started applying a little fertiliser as well.

Five and a half years later the immature trees are growing satisfactorily though none have reached maturity. When these trees come into bearing I expect many to take an interest in growing it. There will also be fruits for trying out its processing and value addition as well as seeds for planting on new lands.

When informed, the Director and the Head of the Plant Science Dept. of the Rubber Research institute of Sri Lanka showed an interest in the species and I was able to arrange for them to collect a lot of seed from NBG in July, 2012. Their intention was to introduce the species to several Rubber growing estates.

Manfred Harrer, a Food Engineer from Colombia contacted me having seen a comment I had made on Pentadesma. In 2012, he flew to Sri Lanka to take back Pentadesma seeds. With these seeds and another lot I sent him later, he has successfully established a pilot project. I have also sent some seed to Vietnam for a trial planting.

Part 2 will be published tomorrow

(The writer is an Associate of International Food Science Centre A/S, Denmark. He can be reached via email [email protected].)