Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 6 February 2017 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

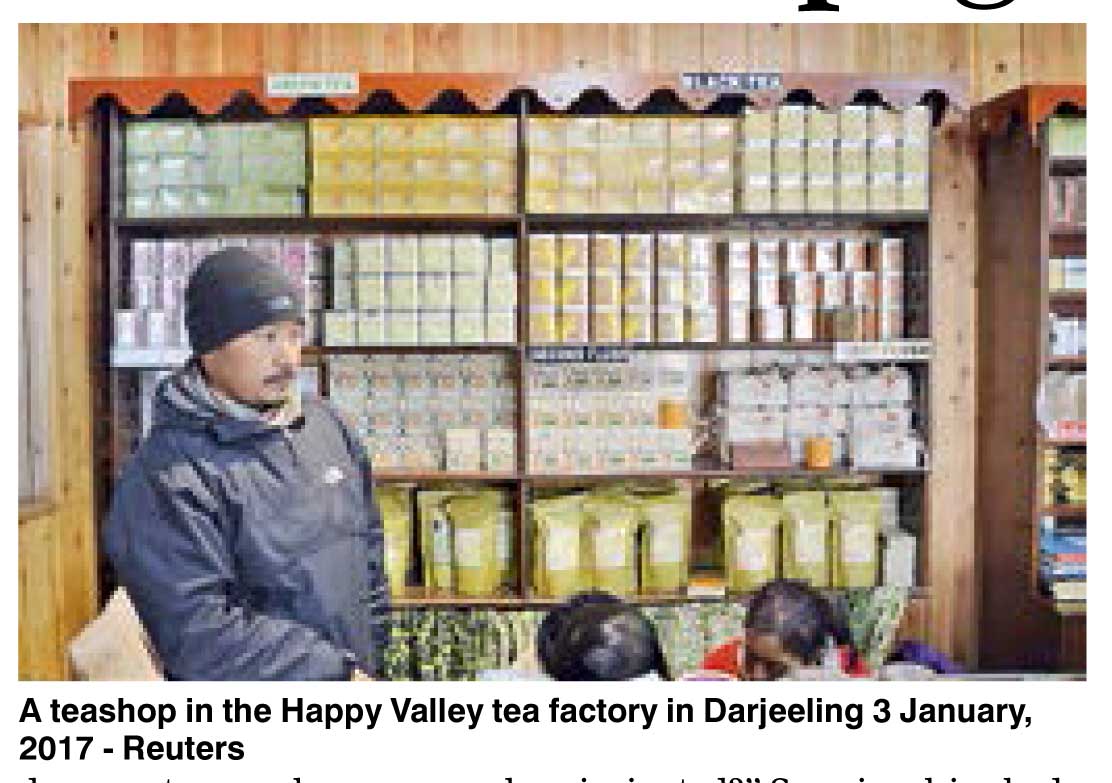

DARJEELING, India (Thomson Reuters Foundation): The future of Darjeeling tea, known as the ‘champagne of teas’ for its distinctive aroma, is in doubt as erratic rains compound other problems facing the industry, estate owners say.

Since 2012, worsening drought – and landslides caused by downpours – have weakened bushes and washed away soil in the famous tea region in the foothills of the Indian Himalayas.

Poor rains have also led to more pest attacks, with red-spider mite, tea mosquito bug and blister blight causing major damage to the crop, local tea experts say.

Yields have fallen to an average of 8,500 tonnes a year since 2010, down from about 10,000 tonnes a year between 2000 and 2009, according to the Indian Tea Association (ITA).

“Darjeeling tea is facing a big disaster,” Arun Singh, head of Goodricke Group Ltd, which has more than 10 tea estates in the region, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“Our crops decline every year due to climatic factors,” he said.

The Darjeeling hills, in West Bengal state, host 87 tea estates employing some 70,000 people. Annual turnover is about 4.7 billion Indian rupees ($69 million) a year.

The change in rainfall patterns is not the only pressure on the beverage, tea growers say. Rising labour costs, the loss of skilled workers to other jobs, falling demand, and aging tea bushes are also hurting tea production, growers say.

Climate change is just an additional obstacle to bringing in a harvest, they say.

“The bushes, which are 75 to 100 years old, need replacing to ensure a better crop,” said Shiv Saria, whose Gopaldhara company has four tea estates in Darjeeling.

The bushes produce less as they age, but replacing them is an expensive business – and one made more costly and uncertain by the erratic rains, scientists say.

It takes several years for the new bushes to start producing a harvest, and many are now not getting enough water to grow properly, according to Subhasish Sannigrahi, senior principal scientist of the Tea Research Association (TRA).

Irrigation is unlikely to be a solution, he said. “Darjeeling does not even have enough water for its growing population. How can the plants be irrigated?” Sannigrahi asked.

This year, as in previous years, the region has not had any rain since December, and growers are anxiously waiting to see what their harvest will be come March.

They have started planting new bushes, and also building walls to stop top soil from being washed away and to protect the bushes from landslides in the event of a sudden deluge of rain.

“I don’t think that Darjeeling tea production will come crashing suddenly, but every year its production is deteriorating, given the climatic and other challenges,” said Kaustuv Roy, head of the tea division of Andrew Yule and Company. ($1 = 68.0452 Indian rupees)