Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 15 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

JAKARTA/KUALA LUMPUR (Reuters): Facing a backlash in Europe over palm oil’s environmental toll, the world’s top producers are scrambling to find new markets and even striking unusual barter deals, such as exchanging Sukhoi jets for the edible oil.

JAKARTA/KUALA LUMPUR (Reuters): Facing a backlash in Europe over palm oil’s environmental toll, the world’s top producers are scrambling to find new markets and even striking unusual barter deals, such as exchanging Sukhoi jets for the edible oil.

The European Union is the second-largest palm oil export destination after India for both Malaysia and Indonesia, which dominate production in a global market worth at least $40 billion. But palm has come under increasing fire in Europe over its impact on forest destruction, encouraging producers to look at new markets ranging from Africa to Myanmar.

Threatened by crumbling demand in Europe, the industry is waging a public relations battle and pushing producers to enter more price-sensitive markets, where Indonesia should have an advantage over Malaysia due to its lower production costs.

“Our principle is we will not let go of even one tonne of trade contract or potential demand palm has globally,” Indonesia’s deputy Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Musdhalifah Machmud told Reuters.

Machmud said palm oil sales were being brought up in “every trade negotiation” Indonesia conducts.

Palm oil is used in thousands of household products, from snack foods to soaps, as well as to make biodiesel.

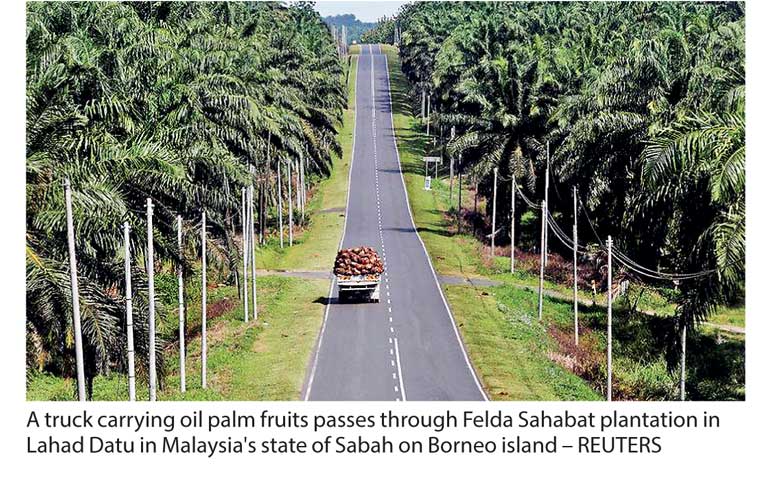

But the demand boom has spread plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia across an area of more than 17 million hectares – an area greater than the size of Portugal and Ireland. They are mostly carved out of rainforests, which critics say has lead to an increase in the greenhouse gases that warm the planet.

Environmental activists have pressured consumer companies into demanding that their palm suppliers adopt more environmentally sustainable forestry practices. But in Europe, politicians say the industry’s standards on sustainability do not go far enough.

So far, palm oil sales to the European Union have held up. Indonesian exports rose about 40% to 2.7 million tonnes in the first half of 2017 from a year earlier.

Indonesia’s overall palm exports were worth $18 billion last year, with EU sales accounting for 16%, the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (GAPKI) said. For Malaysia, the EU made up nearly 13% of exports, government data showed.

Europe is particularly concerned about the soaring use of oils, including palm, as a biodiesel fuel. Once regarded as a green alternative, an EU-commissioned report now says it creates more emissions than fossil fuels.

France said in July it will reduce the use of palm in biofuels over concerns of “imported deforestation”, prompting concerns from Indonesia that other European countries could follow suit.

In Germany, the environment ministry said it will press to amend an EU renewables directive to take account of the study showing “palm oil and soyoil caused, in comparison to other biofuels, very much higher greenhouse gas emissions per energy unit through indirect land use change.”

The European parliament In April voted to phase out unsustainable palm oil by 2020. The resolution endorsed a single Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO) plan for Europe-bound palm and other vegetable oil exports to ensure they are produced in an environmentally sustainable way. In addition to environmental damage, the industry has come under fire over frequent reports of land grabs, child labour and harsh working conditions. Some of the annual forest fires that send shrouds of smoke over parts of Southeast Asia have broken out on palm oil concessions that burn forests to clear land.

Indonesian Trade Minister Enggartiasto Lukita in May warned his EU counterparts that he might ask Jakarta not to buy Airbus planes in retaliation, the Jakarta Post reported.

GAPKI Chairman Joko Supriyono told a United Nations sustainability meeting in New York last week that Indonesian palm oil plantation governance met international standards.

Meanwhile, Indonesia is looking at new palm oil markets in Africa offering barter trades with palm oil. Lukita told reporters on a visit to Nigeria he had proposed to swap palm oil for crude oil.

Indonesia signed a preliminary deal last month with Russia’s Rostec to exchange commodities, including palm, as part of a $1.14 billion payment for 11 Sukhoi jets.

Indonesia’s Vegetable Oil Association executive director Sahat Sinaga said palm oil producers will open a marketing and research company in Russia, aiming to increase exports of 920,000 tonnes in 2016 by 4-5% per year up to 2023.

The group is also planning to open a storage facility in Pakistan, which imports 1-2 million tonnes of palm from Indonesia a year, anticipating further growth in demand.

The Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) says it will increase efforts to diversify into new markets such as Myanmar, the Philippines and West Africa regardless of the EU Resolution.

Malaysia’s plantation industries and commodities minister Mah Siew Keong said in June he met EU commissioners and members of parliament for talks. The ministry did not respond to a request for further comment.

Malaysia is more reliant on palm oil exports than Indonesia, shipping out more than 90% of its palm oil last year, compared to about 70% in Indonesia.

Production costs in Malaysia are also 10-15% higher than in Indonesia, analysts estimate.

“If EU doesn’t take up palm for biodiesel, demand for palm oil globally will fall and prices will be affected on the downside . . . which will impact everyone equally,” said Ivy Ng, regional head of plantations research at CIMB Investment Bank.