Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday, 17 March 2020 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Productivity incentives and other alternative wage models have long been championed by the RPCs as holding the potential to dramatically increase worker earnings, however they have been vehemently opposed. Such opposing parties often claim that it is unfair to ask more of RPC workers – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Breaking its silence on deadlocked proposals around estate sector wages, The Planters’ Association of Ceylon issued a statement clarifying its position on stalled negotiations that commenced on the directive of the Government on 14 January.

In deference to this presidential directive, CEOs and other officials representing the 21 Regional Plantation Companies (RPC) met with various different stakeholders including Government officials and trade union leaders on 17 separate occasions with a view to reaching a compromise on wages.

Throughout, the RPCs had maintained that a feasible compromise to deliver the demand of a monthly wage of Rs. 25,000, without pushing the dangerously escalating cost of production and gratuity payments any higher, should be the priority.

Multiple alternative wage models capable of enhancing earning capacity have been proposed and tested on a pilot basis by RPCs with great success. The most promising of these has been the revenue share model, which aims to convert workers from daily wage earners into entrepreneurs who – much like tea smallholders – would be placed in charge of a given block of land and would be paid based on their harvest. Such a model would offer vastly greater flexibility, freedom and dignity to estate sector workers.

This would have been fundamentally empowering for RPC workers, who could then decide when they want to go into the fields, and work according to their own time, while balancing their obligations to family. In instances where such models have been piloted, there are examples of RPC workers earnings between Rs. 40,000-Rs. 80,000 in a single month.

The final proposal put forward by the RPCs calls for a 2kg increase to the estate norm for tea and a 1kg increase in rubber, together with a return to a productivity and attendance linked wage structures, which had previously been agreed to by trade unions and the Employers Federation of Ceylon (EFC) on behalf of the RPCs in 2016, but was later scrapped solely on the instance of trade union leaders during the protracted negotiations of 2018.

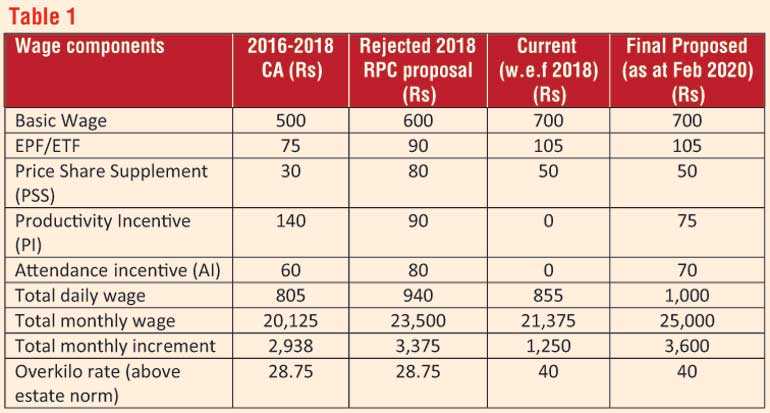

In December 2018, trade unions declared strike action in response to the industry’s penultimate offer of a 20% increase on the basic wage up to Rs. 600, a 33% increase in the AI up to Rs. 80, and a 20% increase in ETF/EPF up to Rs. 90 in addition to the PI and PSS, leading to a maximum total daily wage of Rs. 940, amounting to an average increase of Rs. 3,375 per month per worker.

Following further heated negotiations, a final deal was struck for a monthly guaranteed wage of Rs. 21,375. Crucially, at the insistence of the trade unions, all proposed productivity and attendance incentives were scrapped, despite them raising the possibility of workers earning in excess of what they were demanding, provided they raised their productivity by just two kilos more.

“Our industry has been facing some of the lowest prices on record at the Colombo auction. There were multiple reasons for this, including rising international competition, weaker buyer-side demand in key export destinations, as well as depressed auction prices – despite their being increases in FOB prices which are yet to be fully explained by exporters. These external conditions are also worsening due to recent impact of corona virus and the collapse in oil prices – which has further eroded the buying power of some of our most important export destinations like Russia. In such an environment, RPC costs of production have risen to Rs. 631 whereas our General Sales Average in December stood at Rs. 508. While the GSA has shown some improvement since then, these top-line improvements are totally cancelled out by further increases in cost of production.

“Despite this, trade unions insist on sticking to such archaic wage models as the daily wage system – which are rooted in a colonial past and best suited to the 1800s. This is an absurd position that does nothing for the workers themselves. As mangers, we would like nothing better than to simply give Rs. 1,000 a day or more, but given the fact that we are selling a product at a lower cost than we are producing it, how could such a path possibly be sustained without throwing the entire industry, and the nation into further debt? We are all experienced professionals who are legally bound to take decisions that will not result in our companies going into bankruptcy.

“All we are asking for in return for such an increase is a firm commitment to a marginal increase in productivity, but the trade unions are adamant that they want something for nothing, even if it collapses the industry. Given how unreasonable these demands are, we are confident that the Government will intervene prudently,” PA Official Media Spokesman, Dr. Roshan Rajadurai explained.

Productivity incentives and other alternative wage models have long been championed by the RPCs as holding the potential to dramatically increase worker earnings, however they have been vehemently opposed. Such opposing parties often claim that it is unfair to ask more of RPC workers.

Responding to these arguments, the PA stated: “Over the past few months we have been treated to many pundits who have emerged from the woodwork to make laughable claims in the media that increasing productivity using incentives is everything from inhumane to impossible – despite having zero practical experience in such matters. We wish to put those to rest once and for all.

“Estate norms usually average out at 18kg or more, while plucking averages based on this ancient daily wage model are between 18-21 kilos. On estates where the revenue share models have been practiced, workers have harvested an average of 30-35 kilos. But when traditional norm plucking has been undertaken, they have continuously averaged around 18kg. Hence we have clear proof that we can increase earning capacity by changing the wage model away from the age old norm plucking daily wage system.

“Typically, when men are deployed as harvesters in estates with older tea bushes which have lower yields, they are still able to harvest 16-18kg in just four hours. Usually our female harvesters are able to work faster than the men, and are deployed to harvest our most productive fields, so this idea that we can’t increase productivity is difficult to take seriously. Even in low country smallholder estates which are paid less than RPC workers at Rs. 30 per kilo, they are able to work in the sweltering heat and on terrain which not maintained nearly as well as in RPC estates and still pluck well in excess of 30 kilos. During the recently-concluded Best Tea Plucker Competition, we saw the winners plucking 19.4 kilos in just one hour! So the idea that we can’t even raise output by a mere two kilos by simply altering the wage model is simply and demonstrably untrue,” Dr. Rajadurai stated.

Another limiting factor on productivity in the field is the gang system – wherein tea harvesters working according to the daily wage model enter the field, harvest and take their breaks as part of a gang. Such systems have persisted for over 150 years, and are fundamental roadblocks to enhancing productivity given that typically, the most productive members of the gang are compelled by peer pressure to limit themselves to a speed of work that is in range of the plucking average of gang.

The PA went on to emphasise the fact that even going by the provisions of the 2016-2018 Collective Agreement between the EFC and Trade Unions, RPC estate workers were earnings sums far in excess of the national minimum wage for Government sector employees, paddy farmers, and others in the agriculture sector.

According to the provisions of the National Minimum Wage Act No.3 of 2016, the minimum monthly wage for all workers in any industry or service in Sri Lanka is Rs. 10,000, while the national minimum daily wage of a worker will be Rs. 400. Currently, Sri Lankan estate sector workers earn Rs. 21,375, provided they attend work for 25 days a month. If the most recent proposal on wages is accepted, this figure will increase to Rs. 25,000 per month. Notably, even under the previous agreement, monthly earnings stood at Rs. 20,125 per month. All of these figures are more than double the monthly minimum wage.

Hence contrary to the multitude of continuous criticisms which the industry has been subject to, RPC workers remained among the highest paid when compared with the tea smallholder sector which pays a daily wage of Rs. 590. Meanwhile workers in Sri Lanka’s often celebrated garment sector also receive monthly basic wages far below what RPC workers are paid with an average salary of Rs. 16,100 for 45 hours of work per week. The crucial difference being that garment sector workers are provided comprehensive incentives to raise their productivity, a move which the plantation sector has been consistently attempting to emulate in the face of stiff resistance.

“With the current system, we are obligated to offer 25 days of work, and if an employee comes in, and doesn’t even meet the plucking norm, we are obligated to pay Rs. 855 per day. This is so even if there is a drought, or low plucking, their lifestyle is not affected. Compare this to the plight of anyone else in the agri-sector, or even the dynamic and prosperous smallholder sector. If smallholders produced the same output as RPC workers, they would only earn Rs. 540 per day! If the weather was bad, or if they fell ill and couldn’t work, they would earn nothing. If a factory near them closes, they will have to spend on transport to sell to another factory – these are issues which are already unfolding in the sector as we speak and they are all hardships which RPC employees are insulated from,” Dr. Rajadurai noted.

By contrast, RPC plantation workers receive fully secured, guaranteed lifetime family employment with a mandatory 300 days’ work per year from 18 to 60 years until they retire. RPC workers are also paid EPF, ETF, Gratuity, 17 days paid holidays per year, attendance bonus, profit bonus, profit share, maternity benefits, three months fully paid maternity leave, free maternal and child care on the estate itself from conception to five years, free issue of medicines, drugs, vaccinations and vitamins, total Custodial Child Care on estate from three months to five years, all vaccinations from birth up to five years for children on the estate itself with paid leave granted for mothers. This is a system of benefits which is unique to Sri Lanka alone.

Also notable is the fact that while the sector’s workforce has dwindled to 135,000, RPCs still have to provide care to an extended population in excess of one million individuals, meaning that for every RPC worker, they provide care for another six individuals.

Moreover, Sri Lanka continues to pay the highest daily wage rate to its tea harvesters even in terms of US Dollar value at $ 4.72 per day whereas even today, other tea economies are paying closer to $ 2.5 per day.

Sri Lanka lags behind global competitors in plucker productivity. Plucking average in Sri Lanka’s largest competitor nations, Kenya, stood at 60 kgs, South India at 50 kgs and Assam with 36 kgs, where the norms in those nations had been set at 40 kgs, 34 kgs and 24 kgs respectively. Meanwhile, the daily wage in Kenya stood at Rs. 443.3, South India at Rs. 487.2 and Assam at Rs. 342 in 2016.