Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 3 September 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

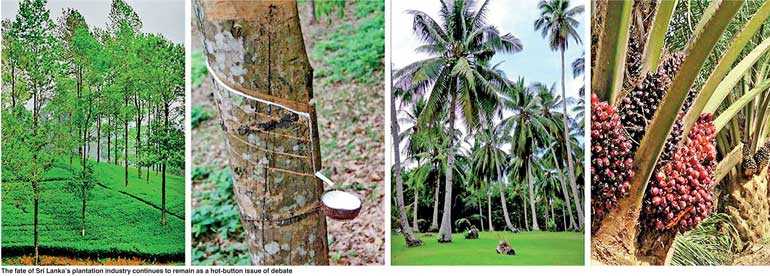

With the fate of Sri Lanka’s plantation industry continuing to remain as a hot-button issue of debate in the media, numerous views have been aired on the rationale behind the privatisation of State plantations in 1992.

In order to clarify the facts regarding privatisation and the conditions which made it necessary in the first place, the Planters’ Association of Ceylon facilitated a discussion with one of the prominent individuals who rendered yeoman service to the nation by helping to drive reforms to the industry at a time when they were sorely required: Dr. Romesh Dias Bandaranaike.

Having been closely involved with the initial privatisation, Bandaranaike was able to offer unique insights into the journey towards privatisation and some opinions on its legacy 25 years later.

“Going back to the time before privatisation, the plantations in the late 1980s were the biggest source of political patronage in the country. Politicians were using the resource to give jobs, transport contracts and provide numerous other benefits to their supporters. Even small portions of land itself were hived off for private benefit.

“The plantations of that era were constantly subject to political interference. The Management was not allowed to operate freely and were often forced to hire political appointees. Transfers and disciplinary actions were also frequently interrupted. This meant that even when people were caught being crooked, they were still retained. Meanwhile, numerous individuals with influence were attempting to profit off these plantations, and encroachments on these lands were becoming the norm,” Dr. Bandaranaike explained.

Given the magnitude of unethical political capital vested in the State plantations, and the inarguably worsening position of these estates as a result, he explained how it became clear to all stakeholders that some kind of radical reform would have to be implemented to save the industry and economy from collapse.

“From a numbers perspective alone, with the exception of a short period in 1987 when there was a huge boom in international markets, the Janatha Estates Development Board (JEDB) and the Sri Lanka State Plantations Corporation (SLSPC) made continuous losses and had to be heavily subsidised by the Government to the tune of Rs. 1 billion per year – which would be equivalent to Rs. 5 billion today,” Dr. Bandaranaike added.

He noted that a further Rs. 8 billion, five times as much in today’s rupees, was owed by the JEDB and SLSPC to the Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank as a result of a $ 300 million lending facility which was extended to the State plantations by the World Bank. While these funds were intended for the improvement of the plantations industry, there were no significant improvements and the plantations did not have the ability to repay the debts, and the Government was eventually compelled to absorb this debt.

The strategic thinker behind the privatisation exercise was the highly respected former Ministry of Finance civil servant, Faiz Mohideen, who later went on to become the Deputy Secretary to the Treasury, while Bandaranaike became the public face of the exercise. Overall guidance and connection to the highest levels of Government were provided by a three member Steering Committee chaired by the Secretary to the Treasury. Bandaranaike explained how an uphill battle was fought to bring industry stakeholders together to hold a discussion on the future of the Sri Lankan plantation industry and to find a way forward through the quagmire it found itself in following the assumption of management by the State.

“While the exercise as initially presented to the stakeholders was purportedly to find ways to improve the operation of the JEDB and the SLSCPC under State management, ultimately it was the then Chairman of the JEDB who first acknowledged that any measures identified as necessary to reform the plantation industry would be impossible to implement within a State-managed framework. There was simply too much bureaucracy and politically motivated interference to get anything done. The only hope was to bring in private management.”

“Once it was clear to the main stakeholders that efficient operation of the nationalised plantations was not a feasible option under State management, developments moved at a fairly rapid pace. Cabinet approval was granted by the then President Premadasa’s regime to bring in private management into the plantations under contract while the Government still retained ownership.

“Tender documents were drafted laying out clear criteria on how the selection would be done. A number of Sri Lankan companies with the necessary financial and management strength applied and following a detailed analysis, management contracts were awarded for 22 Regional Plantation Companies made up of most of the estates of the two State plantation corporations. This all happened with a sense of urgency because the damage that was being done to plantations under State management could no longer be denied,” he explained.

“Everything was done according to a strict procedure because we wanted these reforms to be above-board so they would last. In fact, after she was elected, President Kumaratunga appointed a Committee headed by the then Secretary to the Treasury to investigate and report on the exercise of bringing in private management. The Committee report gave a clean bill of health to the process.”

“After some years of private management on a profit share basis without direct investment it became clear that the private sector needed to invest its own funds into the estates to get the best out of them, because the Government could not afford to do so, and also because this was the best way to ensure that invested funds were not wasted but put to profitable use. This was the next stage, which happened under the Presidency of Chandrika Kumaratunga, when the private sector purchased shares in the RPCs, resulting in full privatisation.”

“In the context of the entire privatisation exercise, it is vital that we all understand that while it is proper to debate methods through which plantations can be improved, we must all remember that no matter how bad the situation gets, there can be nothing worse than a reversion to State management,” he added.

Commenting on the present status of the RPCs, Dr. Bandaranaike noted that producers – RPC and smallholder alike – were likely to benefit from a re-evaluation as to the approach and model for selling tea.

“The auction system that we have in place at present is problematic. Especially in today’s world where we have such a large volume of transactions taking place online, it seems like a relic of a bygone era. We must look at ways of allowing producers to link up with buyers more directly.

“There are instances when a single buyer will be able to purchase the entire produce of an estate if it is of a suitable quality and effectively marketed. We have to streamline our processes to cater directly to these types of niche opportunities while also adding more value locally,” he stated.

However, Dr. Bandaranaike noted that moving to a completely free market for tea sales without interference and sales regulations by the State is bound to be difficult to achieve because of the large number of parties, including in the private sector, with a vested interest in continuing the present arrangements.

He further noted that another crucial factor for the industry moving forward will be with regard to succession in leadership in a manner that preserves and enhances the knowledge base of future leaders in the plantation sector.

“Ultimately, it is crucial to have intelligent, knowledgeable, people in charge, not just at the heads of the companies, but also at the superintendent level. More often than not, a good superintendent will make even an estate that performs poorly produce significantly better results, whereas a bad one put in charge of a profit making estate can bring down productivity and profitability in short order.”

“Over generations, planters have developed their own systems of meticulous record keeping that has helped to pass on knowledge on best practices for each estate, but I believe more work can be done to codify this information and pass it down. Ultimately it is not just about good agricultural knowledge. Good management also requires good relationships with employees and the ability to motivate them to perform,” Dr. Bandaranaike suggested.

In the context of growing challenges facing the industry as a result of fluctuating international market prices and sharp variations in productivity as a result of adverse climatic conditions he also advocated for the creation of reserve funds within each RPC to be set aside to handle future “bad” years, which are guaranteed to arise from time to time.

Shifting his attention to the ongoing losses of the State-owned plantation sector, these were the estates which for a number of reasons were not included in the original exercise of bringing in private management, Dr. Bandaranaike called for the further privatisation to be carried out of these estates in smaller blocks, than the present RPCs. The Government is presently subsidising losses by these estates exceeding Rs. 1 billion per year. Provident fund and retiring gratuity payments are also very much in arrears in this sector.

“In my view these lands, after excluding areas which fall within conservation areas, should be sold outright to anyone who can come up with a sustainable, profitable business model, after making suitable arrangements to address the relatively small amounts of labour on these lands. While some lands would inevitably just be acquired by speculators, they will ultimately end in the hands of those who wish to put it to productive use. There would definitely be some innovation, and even if it is to set up a boutique hotel; that is still a more productive use than what is taking place under state management with most of these lands,” he said. “With agricultural innovation, such as successful growing of a new crop, if one person makes a success of it, others will follow, this is the Sri Lankan model of entrepreneurship.”

“One of the main obstacles to this type of privatisation is the Land Reform Act, which restricts ownership of agricultural land to 50 acres per person or company. In my view, there was an original rationale for the Act, because land ownership before its implementation was highly skewed, mostly due to historic reasons, either because some ancestor got large tracts from past kings, or handouts given by the British to favoured parties. There has now been a redistribution of these lands and there is no longer any reason to restrict ownership, particularly when viable commercial agriculture needs tracts of land much larger than 50 acres. However, I do believe that this legislation will eventually be replaced.”