Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 11 November 2019 00:42 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Tea Exporters Association

The sustainability of Ceylon Tea or the Sri Lankan tea industry depends on how efficiently and effectively it can adapt to match the changing global consumer preferences and consumption patterns. The tea industry needs to be competitive in production, marketing, logistics and product form etc. It must face the market realities and redefine its business strategies and reposition the product lines to achieve this task.

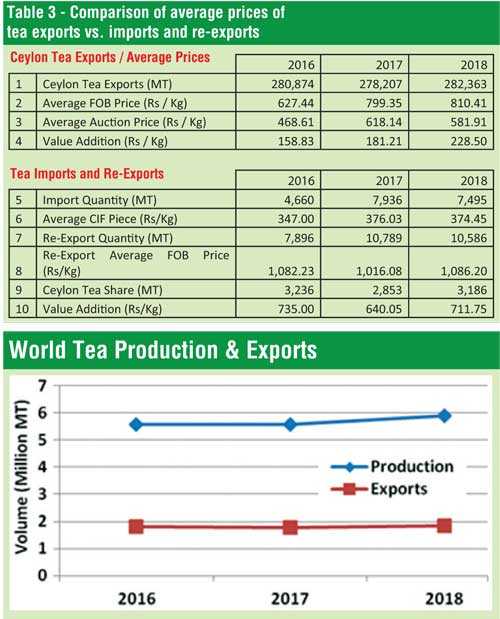

The global tea market is highly fragmented, with several players occupying the market share. At present, about 35 countries produce and export tea, allowing the international buyers a wide range of selection of products. According to available data, in 2017 the world tea production reached 5.69 million MT, registering a growth of 124 million kg over 2016, but the world tea exports recorded a decline of 9 million kg. The growth in world tea production continued in 2018 as well, and registered at 5.89 million MT, an increase of 134 million kg over 2017, but exports increased only by 63 million kg. As a result, the year 2019 commenced with a surplus of about 200 million kg in the world tea market, making a huge challenge to the tea-producing countries to adapt to the global tea market situation.

Currently Sri Lanka tea is sold through the Colombo Tea Auction that brings many buyers and sellers to a single platform, leading to a very transparent price discovery. The free interplay of supply and demand in the auction system creates a competitive environment and determines the correct price. The tea prices are also influenced by the quality and product reliability. The auction system ensures that the highest bidder is awarded the tea and there is no squeezing of prices as claimed by some producer members. The average tea prices realised at some world tea auction centres during the last three years reveal that Colombo Tea Auction always get better prices than its competitors (Table 1).

Imposing a minimum price for tea at the auction will drive away the demand which is currently experienced. The producer has all the liberty to withdraw any tea from the auction if it does not fetch a reasonable price. Whilst all other producing countries are liberalising the sale of tea, we are trying to impose more restrictions. It’s globally accepted that the market forces will determine the best price for any product or service.

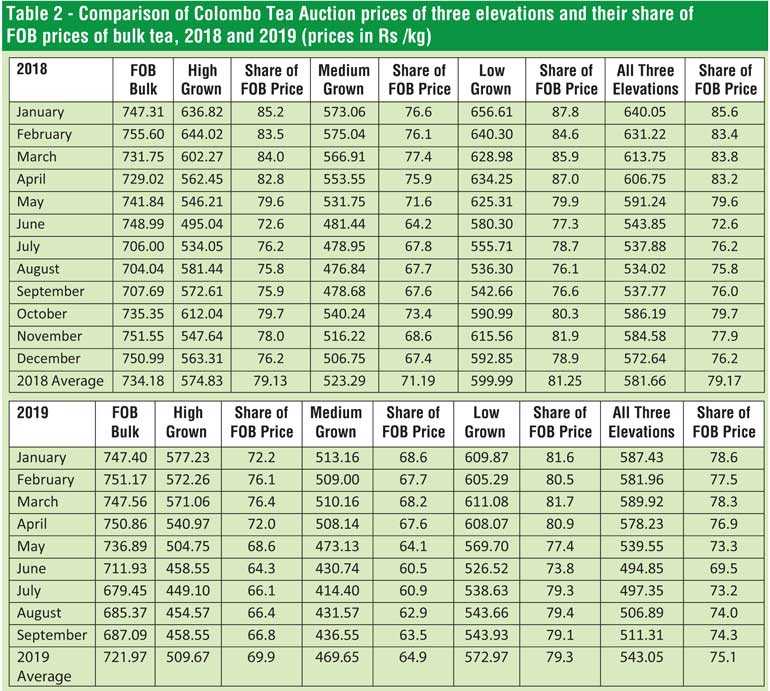

The low grown elevation contributes about 64% to the annual Sri Lanka tea production, while the contributions from high and medium grown elevations are about 21% and 15% respectively. The bulk tea shipments contain either high grown tea, low grown tea or blends of all three elevation teas. Therefore, comparing average FOB prices of bulk tea with average auction prices of high grown tea gives a distorted picture on the tea auction and export prices (Table 2).

Buyers’ conundrum

The above data reveals that, the cost of tea or producers share in the average FOB price of bulk tea is between 75%-80%, leaving only about 20% - 25% to the exporter. It should be noted that, the share of export price received by the exporter is not his profit but the available portion of the export price to meet all his expenses.

The Colombo Tea Auction by-laws require that buyers settle the full cost of tea to the producer within seven days after purchase of tea from the auction, compared to 14 days in Kenya. The exporters of bulk tea are compelled to offer 60-120 days of credit to foreign buyers due to the heavy competition in the world tea market. In respect of markets like Iran, Syria, Russia etc., longer credit periods are offered, as the buyers need more time to pay the suppliers due to international sanctions on their banking systems. However, the exporters are expected to operate at the tea auction every week to procure their tea requirements, and also to support the producers with borrowed money from banks at high interest rates. Hence the finance cost is a major element in the cost structure of tea exporting companies. The other costs of company overheads, storage, transport, freight, tea flavour, CESS and Tea Promotion Levy etc. are also to be met within the 20% – 25% share of the export price. The export CESS and Promotional Levy account for approx. 2% of tea auction price and payable in advance. The tea producers are a fortunate group to receive the payment within a very short period of seven days, compared to other producers / suppliers in the country.

The tea exporters expect a guaranteed product from the tea producers when they purchase tea at the auction. The compliance with ISO 3720 minimum standard, free from any extraneous matters and compliance with international food safety standards are some of the quality parameters expected by the tea exporters. However, most tea producers do not strictly adhere to such requirements, and as a result, the tea exporters have been compelled to invest in tea cleaning machinery also for cleaning of tea before shipping to foreign buyers. The exporters bear additional expenses to ensure the purity of tea to foreign buyers, when it should have been done by the producer before teas are offered for sale.

Decline in quality and production

The decline in tea production in Sri Lanka during the last six years has led to an unethical competition for green leaf. The traditional plucking norm of “bud and two leaves” has been forgotten by many producers. The quality standards of tea produced 10-15 years ago have deteriorated substantially resulting in depressed prices at the auction. Sri Lanka was famous for production of quality tea, and it appears that some producers have forgotten of how to make a good cup of tea that appeals to global consumer. The producers cannot produce just any tea and expect higher prices. They should produce good tea that is required by the international buyers. There is a substantial price difference between the good tea and poor tea at the auction, and producers should make every endeavour to enhance the quality of poor tea that could automatically increase their auction averages.

Ceylon Tea was the preferred component in the blends of many multinational brands some years ago. Due to the deterioration of quality, high prices, and its volatility, most global brands have reduced the Ceylon Tea component in their blends, and today Ceylon Tea accounts for maybe less than 3% in the top three global tea brands. Even the demand for Dimbula and Uva seasonal teas have been diminished, as some producers adopted short term measures to induce seasonal characteristics, which eventually killed the demand and depressed the auction prices. Further, it’s worth mentioning that the demand for mediocre Orthodox rotawane teas is diminishing by the day, limiting the demand only for extraction purposes.

Too many factories

There are too many tea-manufacturing factories in the country, with no noticeable new tea being cultivated. According to Sri Lanka Tea Board, the country has about 710 tea factories for production of 320 million kg of tea, compared to 110 tea factories in Kenya for production of about 400 million kg of tea. Most tea factories operate below their capacity, due to non-availability of adequate quantities of green leaves, and as a result the cost of production is very high. Though the volume of tea crop has declined during the last six years, the numbers of tea factories remain the same. Due to high demand for bought leaf, the factory owners accept any quality of green leaf, and pay premium prices to the suppliers, which is not a sustainable method.

The MRL issue

The EU, Japan, Taiwan and a number of other tea-importing countries have introduced strict MRLs (Maximum Residue Level) for tea imports to ensure safety of the product for their consumer. Although the glyphosate issue was resolved in October last year, high MRLs continue to affect the Sri Lanka tea exports. The exporters get samples of tea tested through foreign laboratories to ensure that they meet with MRLs required by the importing countries prior to effecting the tea shipments. The exporters spend a substantial amount of money on testing of tea samples as each test cost about $ 200.00 per sample. Such expenses are also to be borne within the exporters’ share of the FOB price. In the recent past, some tea shipments were returned from Germany and Taiwan due to high MRLs and other quality issues, but exporters have no recourse either from producers or state regulatory bodies. The MRL issue has driven away some premium buyers, resulting in a decline of tea prices at the Colombo Tea Auction. The producers are required to comply with food safety standards of tea-importing countries as other tea-producing countries are prepared to meet with such requirements. Sri Lanka has already lost and continues to lose market share to Kenya, Vietnam and India over the MRL issue. Ceylon Tea is no longer considered to be the cleanest tea in the world, and is losing its competitive edge.

Value-addition more profitable

The 1981 Sri Lanka Tea Board regulation for import of tea for re-exports was introduced with the objective of promoting export of value-added tea from Sri Lanka. Only CTC tea, green tea and specialty teas are allowed to be imported under the scheme, while orthodox black tea is not permitted. This restricted scheme is monitored by Sri Lanka Customs and Sri Lanka Tea Board, and all teas imported for re-exports are properly accounted for by the regulators. The samples are checked by SLTB prior to importation to ensure that they meet with required standards. All leading Sri Lankan tea brands have benefited from the scheme, and 75% of the re-exports are in value-added form compared to 35-40% for pure Ceylon Tea exports.

The blend component of re-export of imported tea purely depends on customer requirement or the market segment that is targeted by the Sri Lanka tea brands. The price of imported tea is not a criteria specified in the regulation. However, it is a known fact that price of some imported tea is lower due to the low cost of production, but better in quality than some of the local tea. The re-exported teas are labelled as “Ceylon Tea blended with other origin tea” and not as Pure Ceylon Tea. The value addition accrued through re-exports is more than the value addition per kg for Ceylon Tea (Table 3).

Most exporters have invested in tea packaging and bagging machinery, provide employment etc. under the prevailing scheme for re-export of tea to enhance their brand portfolio, and any tinkering with the scheme could have an adverse impact on the local value-addition of tea, performance of brands etc., and exporters moving away from Sri Lanka to places like Dubai or free zone in India also cannot be ruled out.

Unscrupulous practices

It is reported that some unscrupulous businessmen are engaged in import and export of tea using different HS codes (non-tea). The Sri Lanka Tea Board, Sri Lanka Customs and other regulatory bodies should take action against such illegal activities. If any illegally imported teas are coming to the auction, it can come only through the tea factories, and as such the producers have a responsibility to prevent them coming to the system.

Changing trends

Global consumers are moving away from traditional tea products. The fruit tea/flavoured tea/milk tea/functional tea and RTD products etc. are the preferred tea products among the younger generation. The producers should understand the changing global market scenario and adapt to such changes. If Sri Lanka wants to cater to the mass market of tea, its price may not be acceptable to the packers. On the other hand the specialty tea or the top end of the global tea market is looking for good quality tea, and as per the current standards only about 100-120 million kg of Ceylon Tea will qualify for this segment. It will be useful for the producer segment to have information on world tea market trends regularly, and adapt to changing requirements while controlling their production and operational cost. Most plantation companies have tea export companies within their groups and under the same management, and hence they will be able to obtain first-hand information on the global tea market from their own colleagues.

If the tea producer members are of the opinion that the auction system is not the best and there is more money in the export sector, or believe that they should get 100 % of the export price, they can make use of the facility given by the Sri Lanka Tea Board to export 50% of their production in bulk form direct to the foreign buyers. Then only they will come to know of the challenges, difficulties, and other pitfalls faced by the exporters.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we would like to reiterate the fact that all stakeholders should manage their cost efficiently to withstand the pressure from international market situation. The Sri Lankan tea producers should look at using the modern technology, digitalisation, and product diversification to reduce their operational cost. While the domestic expenditure is controllable, the international prices are beyond the control of all stakeholders. The Sri Lanka tea producers cannot dictate terms to the foreign buyers, unless they can supply a unique product that cannot be matched by other tea-producing countries. Even the traditional low grown markets are not safe anymore as India, Vietnam and Kenya have increased their production of orthodox tea, which is in high demand due to better quality and competitive prices. The policy makers should not make any hasty decisions on the free market operation of the tea industry without consulting all stakeholders.