Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 10 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Chitral Jayawarna

Farming is an inseparable part of humanity. We are here today because of enormous progresses our men and women in past generations have achieved in the agricultural sector. It is the result of collective commitment throughout our civilisation. It has shaped the world.

|

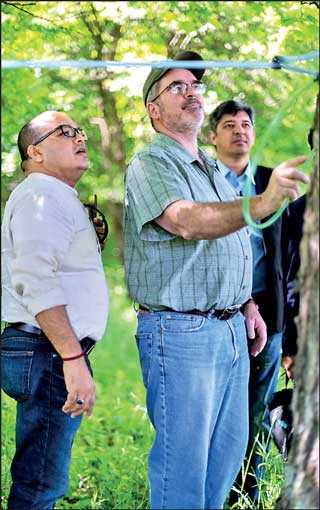

Chitral Jayawarna, Harold Howrigan and Elizabeth Howrigan |

During the training program I was offered to attend recently in USA, we were fortunate to experience an exceptional farming facility in Vermont. Here is their story. This is a story which is bigger than life. This is a story from which we Sri Lanka as an agrarian nation have greater lessons to be learnt.

2019 finds the seventh generation of Howrigans dairy farming and producing pure Vermont maple syrup in Fairfield, Vermont. The multigenerational family farm is now operated by brothers – Lawrence and wife Lisa, Mike and wife Penny, Harold Jr. and wife Bet, and their sons. There are four dairies and the maple operation; they are each passionate stewards of the land. The Howrigans are synonymous with maple and dairy in Vermont and continue a strong commitment to community and industry service; each participates in local, regional or national organisations and boards. They were recognised as the 2007 Vermont Dairy Farm of the year.

The Howrigans have been pioneers in producing pure Vermont maple syrup in these hills of Fairfield since 1876. It is an all-natural product. Nothing is added. No preservatives. Just pure Vermont maple syrup.

“We believe our product is the best in the world; many of our customers agree and return year after year. We consistently win awards and receive accolades at the Vermont Maple Festival, the Vermont Farm Show, the Franklin County Field Days and other venues,” Harold Howrigan Jr. said.

It all started when the younger Patrick Howrigan emigrated from Ireland by way of Canada and brought his parents and siblings to purchase their first dairy farm in Fairfield, Vermont in 1849. His son, William Sr. purchased the former Bailey farm in 1884 which is still the ‘Home Farm’. William, Jr. and Margaret married and raised their family at the ‘Home Farm’.

Harold Sr. was born in the stone house up on the hill. Harold Sr. and his wife, Anne, incorporated as HJ & A Howrigan & Sons, acquired other farmland and began expanding the maple business. Their three sons (Lawrence, Mike and Harold Jr.) and six of their grandsons (Brendan, Harold III, Adam, Ryley, Tim and Cullen) continue their legacy of tradition and commitment to future generations.

The art of making sugar and syrup from the sap of the maple tree (Acer saccharum) was developed by Native Americans of the North-eastern United States. Legend is that maple syrup and maple sugar was being made before recorded history. Native Americans were the first to discover ‘sinzibuckwud’, the Algonquin (a Native American tribe) word for maple syrup, meaning literally ‘drawn from wood’. Initially the maple tree was scored to collect the sap which was then boiled in a caldron until a thick maple syrup.

“We employ a unique blend of tradition with the latest technology to produce our pure Vermont maple syrup every year in the spring. Technological advances have proven to increase efficiency and production. Reverse osmosis is used to remove water molecules from the sap; the sugar content is increased which reduces the time needed to boil the sap precisely to 218 degrees Fahrenheit for our pure Vermont maple syrup....Vermont’s own ‘liquid gold’,” he said.

Sugaring season begins in mid-January and lasts into April. Nights below 32 degrees Fahrenheit and freezing and days that warm into the 40s is ideal. In this beautiful woodland environment sugar maple trees await early spring. Sugar made by the leaves during summer is stored as starch in the root tissues. As winter loosens its grip in February, the sugar maker taps the trees.

A sugar maple that is 10 to 12 inches in diameter at chest height will be about 40 years old and gets one tap. Some large maple trees in Vermont sugar woods are over 200 years old! Vermont sugar makers tap conservatively following recommended best practices. After the taphole is drilled a spout with tubing attached is placed in the hole and gently tapped in place.

Spring’s warmer temperatures coax sugar maple trees to turn stored starch back into sugar. Sap is made as the tree mixes ground water with the sugar. The sap is mostly crystal clear water with about 2% sugar. It takes 40 gallons of sap to make each gallon of maple syrup which has a sugar content of 66.9%. A typical sugaring season lasts four to six weeks. A pattern of freezing and thawing temperatures (below freezing at night and 40-45 degrees during the day) will build up pressure within the trees causing the sap to flow from the tapholes. The sap from pipelines is drawn quickly back to storage tanks at the sugarhouse using a vacuum pump.

From the storage tanks, the sap is put through a reverse osmosis (RO) process to remove a percentage of the water from the sap before boiling. The evaporation process sends clouds of sweet maple scented steam billowing from the sugarhouse cupolas and steam stacks. An evaporator is where the boiling takes place. Stainless steel pans sit atop an oil-fired arch, or firebox, which creates an intense fire of 600 degrees Fahrenheit. As the water in the sap evaporates, the sap thickens and as the sugar caramelises it looks like hundreds of golden bubbles in the front pan. When the thermometer in the pan reaches 219 degrees the syrup is ready.

“Maple syrup is measured by hydrometer or refract meter to ensure that the density, or measure of sugar content, is within a narrow band of 66.9° and 68.9° Brix. This is important to keep maple syrup shelf-stable and to prevent sugar crystallisation within the liquid syrup. The maple syrup is then filtered through diatomaceous earth to remove naturally occurring mineral particles and provide clarity,” Howrigan Jr. explained.

Maple syrup contains an abundance of naturally occurring minerals such as calcium, manganese, potassium and magnesium. And like broccoli and bananas, it’s a natural source of beneficial antioxidants.

Antioxidants have been shown to help prevent cancer, support the immune system, lower blood pressure and slow the effects of aging. Maple syrup is also a better source of some nutrients than apples, eggs or bread. It’s more nutritious than all other common sweeteners, contains one of the lowest calorie levels, and has been shown to have healthy glycaemic qualities.

Maple syrup was the original natural sweetener. Native Peoples in North America were the first to recognise 100% pure maple syrup as a source of nutrition and energy. Since then, researchers have been documenting that maple syrup has a higher nutritional value than all other common sweeteners. In addition, researchers have found that pure maple syrup contains numerous phenolic compounds, commonly found in plants and in agricultural products such as blueberries, tea, red wine and flax-seed. Some of these compounds may benefit human health in significant ways.

100% pure Vermont maple syrup and granulated maple sugar are delicious, healthful and all natural sweeteners that can be used in all your favourite recipes! Substitute 3/4 to one cup of maple syrup for every one cup of granulated white sugar. Decrease the liquid in your recipe by 2 to 4 tablespoons for each cup of syrup used. Add 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon baking soda, unless your recipe already calls for buttermilk, sour milk or sour cream. Also, decrease your oven temperature by 25 degrees as batters containing maple tend to caramelise around the edges more quickly.

Pure granulated maple sugar can be substituted one for one anywhere you use white processed granulated sugar. Maple syrup is now also being used as the sweetener for many value-added products such as: blueberry and other fruit wines, beer and malt beverages, gin, vodka, rum and bourbons, sparkling beverages and aged in bourbon barrels. Maple syrup is also being infused with a variety of herbs and spices to use in beverages, cocktails and sauces.

(The writer is an economist. He is working as Deputy Chief Manager at Sri Lanka Ports Authority.)