Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Monday, 27 June 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Kithmina Hewage, Chantal Sirisena and Suwendrani Jayaratne

On 23 June, Britain became the first country to vote to leave the EU, following a tense referendum and fierce campaigning on both sides. The final result saw the ‘Leave’ campaign win by a small majority: 51.9% to 48.1% and hours later, the UK Prime Minister David Cameron announced his resignation from office by October 2016.

What follows will be significant political and economic upheaval. After 59 years of the bloc’s history, this is a watershed moment and much uncertainty remains over what form the break up will take and the implications for not only the UK, but also its many trading partners, including the rest of Europe.

A tragic split

The EU referendum came about as a result of David Cameron’s campaign pledge for his second term as Prime Minister. He promised to reform the European Union and put it to a referendum before the end of 2017. Voters had been dissatisfied for many years by the continued transfer of power to the EU, immigration issues and the contribution of funds to a region that was struggling to emerge from the global financial crisis.

The issue was gaining considerable traction in the UK and led to the increasing power of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) who won the most votes in the European elections in May 2014 and ultimately spearheaded the ‘Leave’ campaign alongside prominent Conservative Party MPs such as Boris Johnson and Michael Gove.

In February of this year, Cameron finally struck a deal with the EU that would change the terms of Britain’s membership and to take effect immediately if Britain voted to Remain in the EU. The deal addressed many contentious issues including, denying migrants’ in-work benefits for four years and an exemption from “ever closer union”. However, critics of the deal said that it fell short of what was promised and did little to tackle high immigration and taking back powers from Brussels. Ultimately, it was too little, too late.

Demographic divide

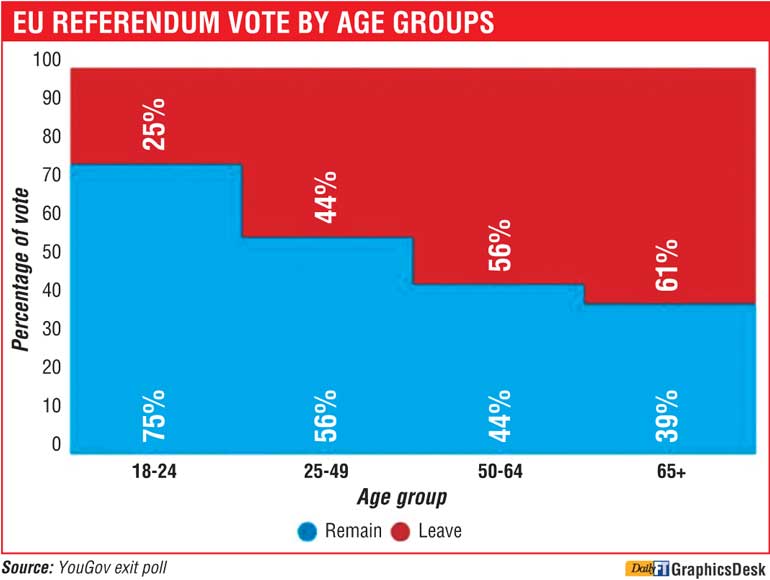

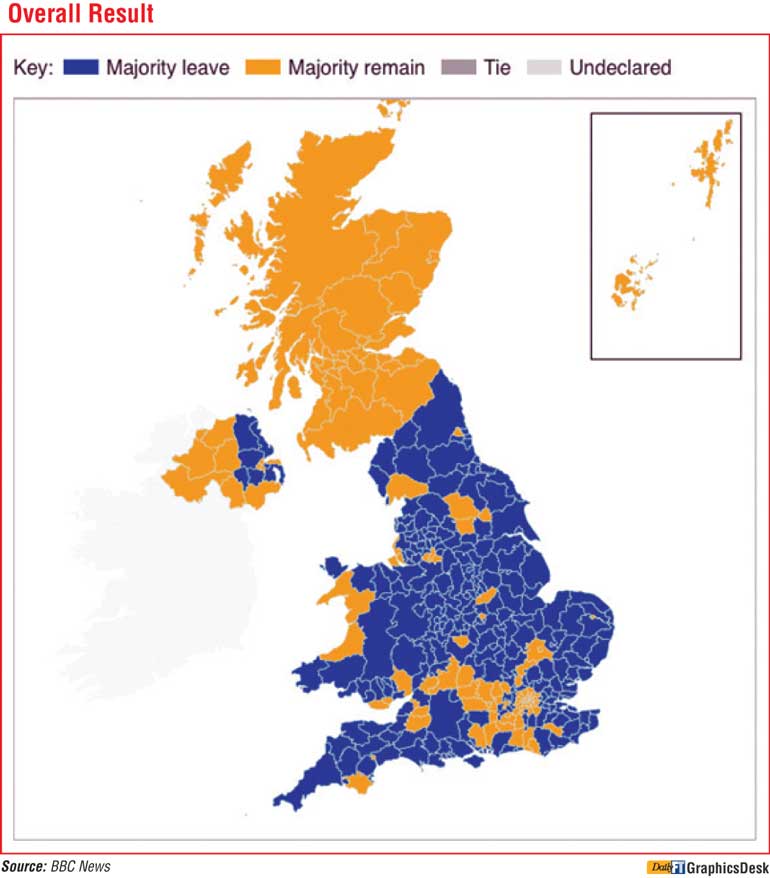

The final result saw a split in voting outcomes across the UK with Scotland (62.0%), Northern Ireland (55.8%) and London (59.9%) voting overwhelmingly to Remain in the EU. As expected, there was also a resounding vote from those under 24, voting to Remain by 75% to 25%. Areas with higher incomes and higher levels of education also had a greater tendency to vote Remain.

Rules for Exit - Article 50

The rules for exit – contained in Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon – are very brief. According to its provisions, the member state needs to notify the European Council of its intention to exit the Union and the two parties will negotiate a withdrawal agreement. Issues pertaining to financial regulations governing the City of London, trade tariffs, and movement rights of EU citizens and UK nations are likely to be included in this agreement. This agreement has to be ratified by the UK Parliament as well as the European Parliament and any member can veto the agreement if they do not agree to the conditions.

Treaties governing the Union will cease to be relevant to the UK at a date agreed in the withdrawal agreement or after two years of notifying the intent to withdraw. In fact, Jean-Claude Junker, the President of the European Commission was quite clear that “Out is Out” and no further negotiations about its status will take place if the UK decides to leave through the referendum. Therefore, in order to provide some policy direction and minimise confusion over the UK’s status in the EU, it is likely that Prime Minister Cameron is asked to trigger Article 50 almost immediately.

Trade with EU

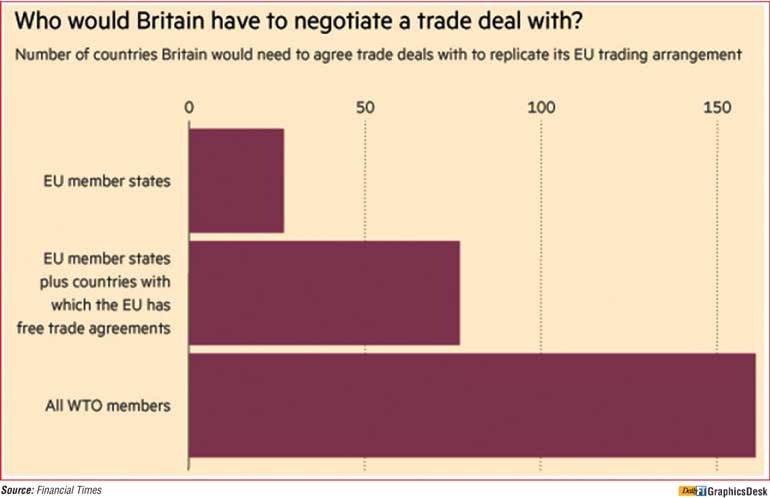

The UK’s trading position with the EU will be a matter of much discussion during negotiations on the withdrawal agreement between UK and EU officials. Upon leaving, the UK will be required to negotiate trade agreements with the remaining 27 members of the EU. These negotiations are likely to be arduous and require considerable political capital, especially from the UK.

The “Leave Campaign” was particularly critical of EU regulations and product standard requirements. Therefore, a new UK-EU trade agreement will have to revisit this issue and if the UK wishes to continue trading with the EU, it is likely that they will be required to re-accept previous conditions, at the least. In 2014, total UK trade accounted for nearly 900 b Euros with EU countries accounting for 53% of UK imports and 48% of UK exports.

Access to other markets

In addition to negotiating trade agreements with the EU, the UK will also be required to negotiate new agreements with other trading partners on a bilateral basis. In context, only 15% of UK total trade currently takes place with countries that are not members of the EU and are not covered by a trade agreement with the EU. The EU has existing Preferential Trading Agreements (PTAs) with 52 countries, and is negotiating agreements with another 72 countries. Therefore, the UK will be required to effectively re-negotiate or start negotiations with 124 countries.

During the campaign period, the pro-Brexit movement noted that the UK could continue to trade under WTO rules without the need for agreements. However, the UK does not possess its own schedule of tariffs, commitments on services, and agricultural subsidies at the WTO. Therefore, while agreements are not required to engage in international trade, they set out rules and regulations that protect UK companies from disputes and arbitrary actions from other countries.

British politics

The political ramifications of the referendum are already taking place with the announcement by Prime Minister David Cameron that he will be resigning from his post by October. The Premier’s resignation will catalyse a leadership battle within the Conservative Party with former Mayor of London Boris Johnson positioned as one of the favourites to take over. It appears that while David Cameron’s gamble to hold the referendum backfired, Boris Johnson’s gamble to break rank on his party leader and support the “Leave Campaign” is about to pay dividends. EU officials, in particular, will be keenly following the leadership battle since the new Prime Minister will be the leading exit negotiations for the UK.

In addition to the leadership battle, regional politics in the UK have gained a new lease of life following the referendum as well. The issue of Scottish Independence from the UK will undoubtedly be revisited after all 32 local authorities in Scotland voted in favour of remaining in the EU. The potentiality of a movement towards Scottish independence was highlighted further when in response to results, the Scottish First Minister and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP) stated that, “the people of Scotland see their future as part of the European Union”. The Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland Martin McGuiness made a similar statement by calling for a vote to on uniting Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

It is important to note that Scotland conducted its own independence referendum in September 2014 and narrowly decided to remain in the UK. However, political sentiments are likely to have shifted considerably with the overwhelmingly divergent directions envisioned by the UK and Scotland. While the direction of these movements is not immediately clear, they appear to be moving towards demanding independence.

Sri Lanka’s exposure to Brexit

Brexit is likely to slow down the economic activities of both the UK and other members of the Union. This will impact Sri Lanka’s exports, given the country’s dependence on both the UK and EU. EU is currently the largest export destination of the country with 28.8% of Sri Lanka’s total exports going to the EU ($ 3 b). UK accounts for 10% of total exports from Sri Lanka ($ 1 b) and 34% of the country’s total exports to the EU. In terms of imports, UK accounts for just 1.9% of Sri Lanka’s total imports and as such Sri Lanka enjoys a trade surplus with UK. Garments (HS 61 and HS 62) are the main export products from Sri Lanka to the UK, accounting for about 80% of Sri Lanka’s total exports to the UK.

Furthermore, if Sri Lanka is successful in regaining EU GSP Plus, the country will only be able to use the concessions till UK withdraws from the EU. Subsequent to that, if Sri Lanka wants preferential access to the UK market it will have to negotiate a bilateral agreement with the UK which is likely to take years given all the negotiations that are likely to place in the aftermath of the exit.

Sri Lanka will also be affected through the volatility in the capital markets. Given that the country is looking at raising capital in the international market, falling investor confidence may hinder its ability to raise funds. Investors have fled to the safety of gold and dollar investments, raising the price of gold to the highest in two years.

Much of the current political and market volatility can be expected to settle over the coming weeks as Britain and Europe provide a clearer direction of proceeding with Brexit. The multidimensional nature of the EU and the significance of the British market are likely to influence the global political economy. Therefore, Sri Lanka needs to closely watch the post-Brexit developments both in the UK and EU and accordingly adjust policies to maximise gains to the country.

(Kithmina Hewage and Chantal Sirisena are Research Assistants and Suwendrani Jayaratne is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka.)