Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Friday, 4 May 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dinesh Weerakkody

By Dinesh Weerakkody

Despite all the negative rhetoric about trade agreements, trade arrangements encourage the free flow of goods and services between the members. These agreements, which can be bilateral or multilateral, reduce or eliminate trade barriers such as tariffs and quotas. As such, they lead to the creation of new markets for businesses, facilitate the production of high-quality goods and enhance economic growth.

Often, changes in international markets can have a direct, positive or negative, impact on poverty. Such an impact may be a result of exogenous shocks (climate change), large market failures (e.g. financial crisis, high volatility in world prices), international agreements (e.g. multilateral or regional trade agreements), and unilateral policies of large economies (e.g. agricultural domestic support or biofuel mandates).

While the impact of these changes vary across countries, depending on their trade specialisation, degree of openness, and adjustment capacities, the domestic redistributive impact among citizens in a particular country can be quite pronounced.

However, there is ample evidence that poverty is not directly the result of a country’s share of trade. Rather poverty reflects low earning power, poor access to communal resources, poor health and education, powerlessness and vulnerability.

It does not matter what causes these features so long as they do not exist, nor what relieves them if they can be relieved. Trade matters only to the extent that it impacts the direct determinants of poverty and that, relative to the whole range of other possible policies it offers as an efficient policy lever for poverty alleviation.

Trade liberalisation may have adverse consequences for some – including some poor – that should be avoided or managed to the greatest extent possible. However, the general belief is that trade liberalisation promotes growth, which in turn, supports poverty alleviation.

In general, only a few people will end up as net losers. Trade policy should therefore generally not be closely manipulated with an eye on its direct poverty consequences, but set on a sound basis overall with recognition that some modification may be inevitable for political and other reasons with poverty being treated by general anti-poverty policies.

Trade barriers

More compelling is the dramatic upturn in GDP growth rates in India and China after they turned strongly towards dismantling trade barriers in the early 1990s. In both countries, the decision to reverse protectionist policies was not the only reform undertaken, but it was an important component.

In the developed countries, trade liberalisation, which started earlier in the post-war period, was accompanied by other forms of economic opportunities for example, a return to currency convertibility, resulting in rapid GDP growth.

Moreover, the argument that historical experience supports the case for protectionism is now flawed. The economic historian Douglas Irwin has challenged the argument that 19th-century protectionist policy aided the growth of infant industries in the United States.

Nor should the promoters of free trade worry that trade openness results in no additional growth for some developing countries. Trade is only a facilitating device. If a country’s infrastructure is bad, or have domestic policies that prevent investors from responding to market opportunities such as licensing restrictions, very little progress can be achieved.

Critics of free trade also argue that trade-driven growth benefits only the rich and not the poor. In India, however, after the economic and education reforms, nearly 200 million people have come out of poverty. In China, which grew faster, it is estimated that more than 300 million people have moved above the poverty line since the reforms were initiated.

Moreover, trade agreements open new markets for businesses, so competition increases. To withstand the competition, businesses are forced to build more quality into their products. Superior product quality means improved satisfaction for consumers. In addition, local consumers have access to a wider variety of products and services.

Biggest problem

Poverty is still the biggest problem in South Asia; large sections of people in South Asia do not have access to even safe drinking water and to basic sanitation services. South Asia is extremely diverse in terms of culture, politics, and religion. Such diversity entails difficulties in promoting regional cooperation. In fact, the speed of regional cooperation in South Asia has been slow compared to other regions.

Over the next few decades, South Asia needs to grow their economies at a much faster pace to eradicate poverty. They will need to strengthen and deepen their democracies and ensure the region is stable and secure. But that can only be achieved, if South Asia works together and promote more and more interregional trade.

With the expansion of markets comes increased business performance. In particular, small businesses can buy raw materials from other countries within the free trade area without incurring any additional costs and sell more goods in the expanded market. This leads to the creation of new jobs, as the businesses need more personnel to support growing operations. For example, according to the US Office of the Trade Representative, 6,000 new US jobs are created for every $ 1 billion worth of exports.

Another challenge for South Asia is to ensure their financial system is stable and easy to access, and also foster a political climate that creates confidence in their region.

Political risks

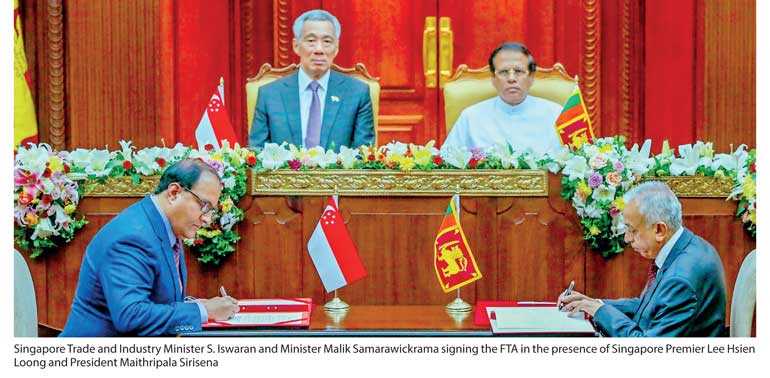

In general, trade agreements like the Singapore FTA can boost economic growth and jobs. With more job opportunities, the rates of unemployment go down and more people have more income they can use to support their families. The expansion of both local and foreign markets gives rise to new businesses, so the country can earn more national revenue from taxes.

However, trade agreements typically have huge political risks that needs to be managed at every stage by competent people. One example would be the movement of skilled talent resulting in local professionals getting displaced.

The story to sell is that trade arrangements, when competently negotiated, will not only boost trade and welfare and the soft political capital, but also provide opportunity for the young to have sustained income streams.

(The writer is a thought leader.)