Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Wednesday, 22 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By S.P. Upali S. Wickramasinghe

By S.P. Upali S. Wickramasinghe

The Innovators to Industry (I2I) proposal is important. We have had many inventions slipping through our fingers and finding their way into other economies and the sad fact is we are quite unaware all these losses taking place. We have asteroids named after our student inventors but today their inventions are not known here.

All of us may know the story of the Land Master of our late Ray Wijewardene; did we ever stop to learn a lesson and correct the system?

I have had two shocking experiences with the Patents and Trade Marks Office of Sri Lanka since 2002, which I think should come to the public domain in order that in the future these things will not happen and also as a warning to those that seek assistance of this institution in the future.

The Patents and Trade Marks regime is bound to be the via media for the country to financially benefit from the sale of patents and trademarks – processes and products developed by the Sri Lankans.

The National Intellectual Property Office of Sri Lanka (Patents and Trade Marks Office) is expected to provide protection and to promote inventions, designs, at the same time be a source of income to the nation.

The sale of patents and trademarks contribute a substantial income to the national exchequer in the developed world. That ladies and gentlemen, is the last thing our Trade Marks and Patent Office considers as their perspective.

I was surprised to find a patent that had been granted by the Assistant Director – Information and Examination, which had a serious technical mistake, which even a student at OL would not have missed. That error should have been corrected prior to the grant of the Patent Licence.

Such a faux pas is not expected from a national body. Since our patents are not in the internet, the country escaped being laughed at.

In December 2002, I filed six trademark applications. Since I was not informed whether the trademarks had been accepted, I sent many a reminders under registered post to the then Director General. There was no response.

Bold silence at the Trademark Registry

A response to those application came only in 2017, that also with the recently-appointed Director General in Office when I reminded her of this problem.

In contrast, I have seen many advertisements by lawyers for trademark owners outside Sri Lanka, with warnings of prosecution if their trademarks are violated – to my knowledge there had been two such “prosecutions”.

I was warned by a leading agriculturist, inventor, academic, to guard myself against patenting any process. He said that when patents are filed, one had disclosed his process and is open to theft of his process by the unscrupulous.

A well-known tool manufacturer in the US had copied, without any reference to him, a tool for which he had obtained patent. The matter was settled by litigation. In that litigation he had been backed by a major company in the UK.

This gentleman did not know me personally, but having heard of my work, contacted me via the editor of a popular English daily. Those days I used to write to the Island and the Daily Mirror regularly.

All industries require energy, which at present is obtained from fossil fuels. The biggest consumer of fossil fuel based energy is the petroleum industry itself followed by the alcohol (ethanol) distillation industry. Any reduction in the requirement of external energy – fossil based – will help to reduce the cost of producing ethanol. Beneficiaries would be found among the users of ethanol as a substitute, adjunct, to petrol and diesel also the alcoholic beverage industry.

I had formulated a process by which the alcohol distillation can be carried out at zero energy. What was required was a minor adjustment to the system – no increase in the inventory.

I have been attempting to sell this process. Every attempt to sell this process since 2002, resulted in the party contacted treating the proposal as being incredulous. In fact one gentleman went the extent of reminding me of Harry Houdeni – a “magician” of sorts or a hoodwinker, a trickster.

Regardless of failed promises and warnings, I ventured to seek a patent for a process which is less controversial. A process to produce a stationery file that could be made to stand erect and can be easily tagged – as in a library. In the library the books are stacked upright, supported on the sides by L shaped steel stabilisers (anchors), by referring to the spine of the book one could identify the contents within.

With that experience, without considering the prior warning, I ventured to the patents Office (SL) without seeking assistance abroad e.g. Singapore or India, to seek a patent for this stationery file that was developed by myself.

I was a fool, I wasted my money. Let this be a warning to other fools who wish to venture to the National Intellectual Property Office of Sri Lanka (Patents and Trade Marks Office). This attempt was to test the waters. The application was filed with the Patent and Trade Marks Office on 17 December 2016 after paying the stipulated fee of Rs. 4,025.00.Ref LK/P/1911.

A patent application is submitted in two sections (i) Prior Art section – where the applicant deals with system that is in existence and pin point their short comings (weaknesses), which he proposes to improve on (ii) the proposed system that will help to overcome the said deficiencies.

My proposal was to improve on the existing stationery filing systems and ways and means of over - coming the identified deficiencies.

The size of the paper that is very popular is the A4 size sheet, 220 mm x 295 mm.

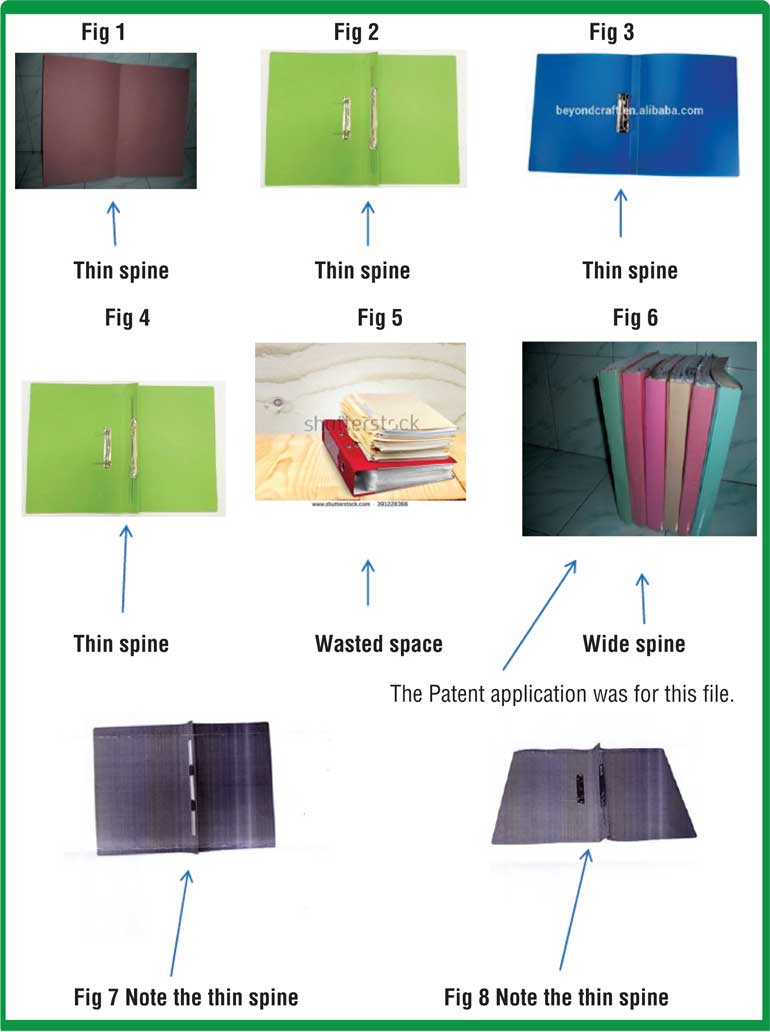

All the filing systems in the market were 240 mm x 340 mm in size. The material of construction were (Fig 1) Bristol boards (Rs. 10.00 per unit), (Fig 2, 3 and 4), plastic board (Rs 60.00 to Rs 65.00 per unit) and (Fig 5) box files with four to eight arched prongs (Rs 400.00 – Rs 440.00 per unit).

The files in Figs 1, 2, 3 and 4 were not rigid, they (i) could not be stacked upright (standing), the papers within tend to sag or hang down (ii) very few sheets could be filed as the spine was either non-existent or not broad enough (iii) the files could not carry the identity of the material within, as they did not have a wide spine (iv) the support to the papers within was at most about 84% of the height of the A4 paper.

In fact in most of these files, the covers fold on itself. The Bristol board cover is the one example. The only system that could meet the base requirement were the (Fig 5) box files with four to eight arched prongs, however they had about 25% wasted space, too bulky and too heavy to carry.

Fig 6 was 220mm x 295mm x 30mm. The spine was 30mm x 295mm.Such a spine can be easily tagged. The material used was a Bristol board. In the photo the files had been anchored by two steel “L” shaped angles on either side. This design provided solutions to all the negative factors identified.

Another positive factor in this design was that it could be in the market at prices as low as Rs 30.00 per unit, providing the manufacturer with a profit margin of about 100%.

As there was no response to this application from the Patent registry, I phoned the office, to be told that the application will be taken up for evaluation only at the end of 18 months of filing.

I contacted the Director General, with the possibility that the extreme eventuality would be the Patent Office granting a patent to a dead body – my age. This led to an evaluation of the application without the 18-month lapse. On 5 June 2017, the Assistant Director Information and Examination informed me that the application was being rejected. The following reasons were adduced.

Lack of novelty

and inventiveness

1. Information disclosed by the above patent application cannot be considered as novel or to involve an inventive step (improvement to technology) when compared to existing techniques/products in the relevant technical field. (Details of some commonly available commercial products are attached herewith for your information). See Figs 7 and Fig 8.

2. Claims do not define novel or inventive technological features but are merely directed to design options of the products such as length, width, material, etc. Hence this application cannot be accepted for grant of a patent under Section 63 of the Intellectual Property Act. Where the said section define a patentable invention should be novel, involve an inventive step and industrially applicable.

3. You may make your written submission against this refusal within three months from the date of the notification.

The submission against the refusal was made on the 22 June 2017 (Registered Post delivered to the front office on the 27 June 2017. There was no response to the submission. A further reminder was sent on the 5 September 2017 (Registered Post) and handed over to the front office on 7 September 2017. No response to date.

The irony of the Assistant Director’s findings was well illustrated by the photographs of the so-called commonly-available commercial products that were attached. See Figs 7 and 8. These files are of the category 240mmx 340mm with hardly any spine (note the A4 sheet is 220mmx295mm). Unfortunately the examples Fig 7 and Fig 8 are the very types that I have said need improvement Ref Fig 2, Fig 3 and Fig 4.

My comments:

1. “Merely directed to design options of the products such as length, width, material, etc.” Those are the basic grounds on which I am seeking the patent.

2. “Claims do not define novel or inventive technological features”. The claim and how novel and inventive was attached to the application/proposal. The application itself was vetted by an officer of the Patent and Trade Marks front office prior to submission.

3. “Should be novel, involve an inventive step and industrially applicable.” An invention is considered novel, when it moves outside the common track, in this case Fig 6 represent a development which is outside the common track viz. Fig 1,Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4, Fig 7 and Fig 8.

An invention need not be design of a rocket engine to have a value. On a US-based inventors forum, I find many simple variations of the standard as being acceptable as a novel product.

The Assistant Director had not indicated the criteria used to determine the sample in Fig 2, Fig 3 and Fig4 as being different from the samples Fig 7 and Fig 8. and promote those files in Fig 7 and Fig 8 as being “suitable”, furthermore the grounds on which the Assistant Director arrived at the conclusion that the file in Fig 6 was not novel, was not indicated. Such arbitrary decisions are not within the parameters of a good judgement.

The variation from the standard is based on the ability to keep it upright, without damaging the documents within. That provided the file in Fig 6 the required novelty and is the inventive step.

Industrially acceptable – nobody, least of all an administrator, could define what is industrially acceptable until it is placed in the market.

However the following should have been a guide to the Assistant Director:

“Considering the economic advantages of the design/patent sought for viz.:

1. The cost around Rs 15 to make – based on retail prices of the materials and machine cost. Prices of files in the market were provided against each design (see above).

2. Could be in the market at Rs 30.00-50.00 per unit.

3. The investment is low and could be recouped within a very short time – few months if not weeks.

4. The potential market could be as high as 3,000,000+ pieces per year.

Under these circumstances I tend to wonder whether anybody at the Patent Registry wished to get into business of making and selling stationery files or had an idea of selling this design to a favourite investor.

One is reminded of what the inventor referred to earlier suffered from.

There are few more comments which I consider sine qua non.

1. There is said to be a latent period of 18 months prior to the evaluation of the application. This is a negative feature, because of the following factors

(i) An unscrupulous employee of the Patent Office could pass on the information to an investor leaving the inventor to bear the loss. (ii) Early approval is the essence of the process. (iii) I have accessed many patents obtained elsewhere in the West – generally the patent is granted within two years of submission. (iv) In majority if not in all the patents granted the identity of the examiner is provided. In some instances, the examiner provides additional sources to justify the grant of the patent.

2. Patents obtained are placed on the internet. This serves two purposes, help others to pin point shortcomings to improve on them and the most important, facilitate the sale of the patent, in which case the net beneficiary is the country.

3. The patent applications should be evaluated by a board of competent personnel, not by an employee of the Patent and Trade Marks Office. The evaluation should be open and the board should expect the patentee to justify his application.

I do not want to be rude, however the manner in which this and the matter on trademarks had been handled make me sceptical of the bona fides of the National Intellectual Property Office of Sri Lanka.

In fact the possibility of some unscrupulous person at the patent office going into business or selling this process to a third party cannot be considered remote. That is Al Caponisque in character.

In which case one could consider that office at Maradana – 400, D.R. Wijewardena Mawatha as a branch of late Al Capone’s office in the US – Al Capone’s office in the Far East.

(The writer could be reached via [email protected].)