Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday, 19 February 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Kithmina Hewage

The UK economy could shrink by 2.5 to 4% in the long run after leaving the European Union (EU), and that’s a best-case scenario. The reality, however, could be starker, as the UK stumbles from one political-economic crisis to another, since its Brexit Referendum in 2016.

Prime Minister Theresa May has failed to garner the required support in Parliament for a proposed deal, leaving the country on the verge of a no-deal Brexit. The situation has been complicated even further with the passage of several votes in the Parliament in January. This article will discuss some key questions regarding the current state of Brexit, potential outcomes, and their respective impacts on Sri Lanka.

What happened since the Brexit Referendum?

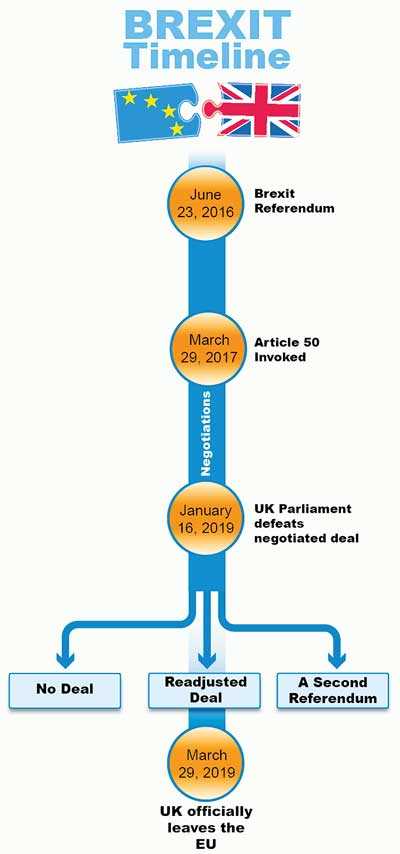

Since the Brexit Referendum in 2016, the UK formally invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on the EU and set a withdrawal date for 29 March 2019. During this time, the UK has also been in negotiations with the other 26 EU nations to agree on a “divorce deal” – an agreement that lays out the terms of exit between the UK and EU.

Contrary to what was promised by pro-Brexit campaigners during the lead up to the referendum, the EU has taken a tough stance in negotiating with the UK. While the EU would prefer that the UK remain in the EU, it is more concerned by other countries potentially leaving in the future. Thus, it is intent on keeping the union strong amidst Brexit, while demonstrating to its member nations with inclinations to leave that they will be worse off outside its membership.

In November 2018, the UK and the EU agreed on a withdrawal agreement and among a plethora of issues, some of the key concerns revolved around how much the UK will have to pay for withdrawing from the partnership (approximately £39 billion), the status of UK citizens currently living in the EU and vice versa, and the avoidance of a physical border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The agreement also established a transition period between 29 March 2019 and 31 December 2020 for both parties to negotiate a trade agreement and allow businesses to adjust more smoothly. However, the UK Parliament overwhelmingly rejected the agreement by a remarkable 432 votes to 202. This represented the biggest margin of defeat by a British Prime Minister in modern history.

Why do so many oppose the agreement?

The biggest point of contention is regarding what is commonly referred to as the “Irish Backstop”. Neither the EU nor the UK want to create a physical border barrier between Northern Ireland (part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (an independent nation which is a member of the EU) due to political and economic reasons. Politically, a physical border may jeopardize the Irish Peace process while from an economic standpoint both countries are heavily interdependent on each other.

Considering this, both parties agreed to establish a backstop, which commits the entire UK to the EU Customs Union, while Northern Ireland is also bound by many rules of the single market, until a long-term trade pact is agreed. This could potentially mean that the UK is bound by EU rules without having a voice in shaping them as an EU member, indefinitely. This proposal, faced severe opposition from hard-line Brexit supporters. Since rejecting this proposal, the parliament has requested the Prime Minister to renegotiate the backstop with the EU, yet the EU has also stated that they are not willing to compromise any further on the matter.

Meanwhile, pro-Remainers believe that the agreement does not provide adequate safeguards to UK businesses that will be affected after Brexit. In a post-Brexit world, British exports to the EU will face tariffs, making them less competitive. Meanwhile, restrictions on the movement of persons after Brexit has also led to several financial companies moving their offices from the UK to mainland Europe. For instance, US banks Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, and Citigroup have already moved $283 billion worth of balance-sheet assets to Frankfurt while HSBC – Europe’s biggest bank – is also moving its European Headquarters from London to Paris.

What happens next?

As noted earlier, the critical deadline is looming. While the Prime Minister attempts to renegotiate a deal with the EU, uncertainty reigns and several potential outcomes exist.

No deal

A no-deal Brexit is the ultimate nightmare scenario for all parties concerned as Britain will move out of the EU overnight with no safeguards or transition periods. Moreover, Britain will also lose any leverage it currently possesses with the EU in order to negotiate a favourable trade deal separately. Oxford Economics forecasts that a No-deal Brexit will knock 2% off the UK economy by the end of 2020.

Meanwhile the IMF predicts a long-term negative impact of close to 7% of GDP growth in the absence of a deal or a negotiated FTA. Similarly, the Bank of England controversially estimated that the UK economy would contract by 9.3% in 15 years of a No-deal Brexit. Cognisant of these impacts, the parliament has voted in favour of avoiding a no-deal Brexit. However, given recent developments, the likelihood of this has increased even further and the British Government has already initiated contingency plans for this outcome.

(b) Readjusted deal

Following the defeat of the deal, the UK Parliament has since passed several amendments instructing the Prime Minister to re-open negotiations with the EU. EU officials, on the other hand, have stated that they are unwilling to open up the legal text for further negotiations. In the unlikely event that negotiations reopen, May could attempt at passing an amended deal – especially regarding the backstop. The passage of such a deal would be a significant political victory for the Prime Minister, but is highly unlikely given the wide spectrum of opposition that currently exists.

(c) A second referendum

If the political deadlock over an amended deal persists and the likelihood of a No-Deal Brexit increases, the Prime Minister is likely to call for a second referendum. While some prefer another referendum that includes the option of remaining in the EU, others believe that it should not be.

Crucially, the European Court of Justice has already ruled that the UK has the right to revoke Article 50 unilaterally, which leaves that option open as a means of last resort for the Prime Minister. That said, the Prime Minister is likely to face severe backlash from her conservative pro-Brexit colleagues if a second referendum was to be put forward. Given domestic rules of a referendum, the likelihood of a second referendum before 29 March is slim.

What does this all mean for Sri Lanka?

The UK is the second largest destination of Sri Lankan exports (approx. 8.3% of total exports) and accounts for roughly 30% of exports to the European Union. Crucially, garments and rubber products are the biggest export from Sri Lanka to the UK (approx. 80% of exports to UK) and they benefit from EU GSP+ concessions. This means that the outcome of Brexit will have a direct impact on Sri Lanka’s export sector. If a No Deal Brexit takes place, the UK will no longer fall under the EU GSP+ and Sri Lankan exports could potentially face tariffs. That said, British authorities have indicated that, at least in the short term, they will extend the same preferential concessions to which they have committed. However, this would require the UK parliament to pass the required legislature and even minor lags in passing such Legislature may have impacts on Sri Lanka. More importantly, the negative economic impact, especially of a No Deal Brexit, on both the UK and the EU could lead to an overall depletion of demand for Sri Lankan exports as well.

Whilst acknowledging the importance of GSP+, however, it is important that the Sri Lankan export sector adjust to an imminent post-GSP+ era. Sri Lanka is projected to achieve upper-middle income status during the next three and five years, and upon graduating to this status, will no longer qualify for GSP+ concessions either to the UK or the EU.

Therefore, considering the potential economic shocks that may arise out of Brexit and the loss of GSP+ in the near future, Sri Lanka is best served by urgently looking at diversifying its export markets whilst also improving its natural competitiveness in order to insulate itself from specific external shocks such as Brexit.

[Kithmina Hewage is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]