Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 23 May 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Bilesha Weeraratne

By Bilesha Weeraratne

Geetha is an unskilled and uneducated female from rural Sri Lanka. As she was saddled with financial issues and could not find a suitable job in Sri Lanka, she decided to seek employment in Saudi Arabia as a Female Domestic Worker (FDW). However, Geetha was clueless about how to proceed, and thankfully Somadasa – a Sub Agent from her village, helped her through the entire process. Now Geetha has a job (for which she did not have to pay any recruitment fees) that pays her a steady monthly income of Rs. 35,000; she also received over Rs. 200,000 as an upfront incentive for taking up the job.

Sub Agents like Somadasa play a significant role in the recruitment of migrant workers from Sri Lanka. However, to-date Sub Agents are informal stakeholders in the recruitment process. As such, currently, there is increasing interest in Sri Lanka to regulate Sub Agents and hold them accountable for their conduct. In this context, IPS carried out a study to better understand the relationship between migrants and Sub Agents and provide empirical evidence for policy recommendations to regulate Sub Agents in Sri Lanka. This blog is based on the findings of the study.

Sub Agents play a critical role in recruitment for foreign employment from Sri Lanka, by linking potential migrants with licensed recruitment agents. Licensed recruitment agents often operate in the city centres, considerably far off from the rural villages where potential migrants reside. This geographical distance limits licensed recruitment agents from adequately reaching out to their clientele. At the same time, the regulatory framework in Sri Lanka restricts licensed recruitment agents from establishing branch offices.

As a remedy to these legislative and capacity constraints, licensed recruitment agents have evolved to rely on Sub Agents, who informally operate at the grass root level in areas where potential migrants originate from, to work as a conduit between a licensed agent and a potential migrant.

This working arrangement between licensed agents and Sub Agents also fits perfectly with the needs of low-skilled potential migrant workers like Geetha, who come from less educated backgrounds and belong to the lowest socio-economic stratum of society. For them, the recruitment process for foreign employment is often strange, intimidating, and complicated. As such, these potential migrants are often reluctant to directly approach a licensed recruitment agent, but are more willing to go to a Sub Agent, who is usually a known person from their village.

Moreover, despite the absence of a formal recognition for Sub Agents, migrants have the misconception that Sub Agents are formal stakeholders in the recruitment process. As such, the services of Sub Agents are common in recruitment of Female Domestic Workers (FDW) to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

However, not all Sub Agents in Sri Lanka are genuine like Somadasa and not all migrants are as lucky as Geetha. As informal stakeholders in the recruitment process, Sub Agents are often criticised for their contribution to debt bondage and trafficking, over charging, forging documents, and misuse of power (i.e. illegally withholding the passports of potential migrants) in the recruitment process for foreign employment. The informal nature of their role and the absence of a regulatory framework to control their conduct contribute to low accountability and high levels of misconduct by Sub Agents.

As such, the government of Sri Lanka is attempting to regulate Sub Agents. However, regulating these informal stakeholders is a complicated exercise.

Similar to the rest of South Asian sending countries, Sri Lanka has previously tried and failed to regulate Sub Agents. In 2012, the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE) issued identification cards to Sub Agents through the respective licensed agents. However, there were more Sub Agents operating in the field than registered, and as a result unethical and unregulated activities of Sub Agents continued.

As such, in 2016 the SLBFE issued a circular requesting all licensed agents to return the identification cards issued to their respective sub-agents. This circular implies the government position of not recognising the operation of Sub Agents. However, the SLBFE did not take action against the non-return of identity cards or the continued operation of Sub Agents.

Now there is renewed interest to regulate Sub Agents. Specifically, in March 2017, a Cabinet Paper with recommendations to regularise Sub Agents was submitted by then Ministry of Foreign Employment, while the SLBFE is actively engaged in attempts to revise its Act to incorporate regulation of Sub Agents.

One common element across all these failed attempts is the lack of empirical evidence to guide regulatory efforts. The following are some interesting empirical findings on the unique and dynamic relationship between migrants and Sub Agents that are valuable for regulating Sub Agents.

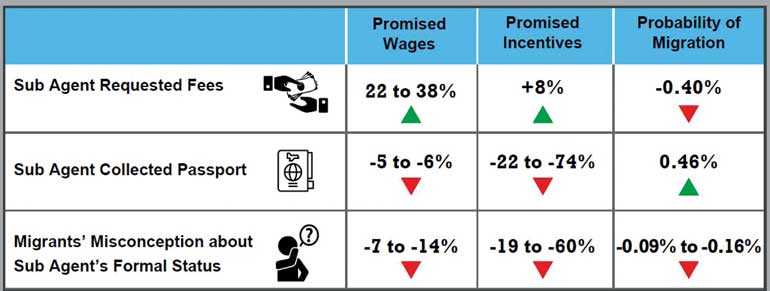

Based on rigorous analysis, the IPS study finds that:

Migrant’s misconception that the Sub Agent is a formal stakeholder leads to lower probability to migrate, lower promised wages, and lower promised incentives. When potential migrants are unaware of a Sub Agents’ actual formal status and have a misconception that they are formal, potential migrants are more likely to be intimidated, leading to accepting lower wage and incentive offers. Similarly, with such intimidation, potential migrants are less likely to follow up and pressurise Sub Agents about migration.

Collection of the migrants’ passports by Sub Agents leads to lower promised wages and promised incentives, but a higher probability to migrate. As per the existing regulations, as informal stakeholders, Sub Agents have no authority to collect passports. However, in practice, it is the Sub Agent who initially collects the passport from the potential migrant and hands it over to a licensed recruitment agent. As such, there are instances where Sub Agents hold on to passports while they ‘shop around’ for alternative licensed recruitment agents, until an attractive commission is offered to the Sub Agent. Simultaneously, this submission of passport deprives the potential migrant of alternative offers, as she is unable to approach other licensed agents or Sub Agents. This leads to lower bargaining power and related lower promised wages and incentives for potential migrants. However, lower financial outcomes are in the context of higher chance of migrating, because a passport is needed to process the final steps of the migration process, and often these final steps are carried out by the Sub Agent on behalf of the licensed agent.

(Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To share your comments with the author, please write to [email protected]. For more articles, visit our blog http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

A Sub Agent requesting money for his services leads to higher promised wages and higher promised incentives, but a lower probability to migrate. The status quo for recruitment of a FDW to the GCC countries involves zero recruitment cost to migrants. Yet, this finding reveals that recruitment fees are collected by Sub Agents, resulting in contradictory implications to potential migrants. Higher promised wages and incentives, coupled with lower chance of migration reflect the misleading nature of Sub Agents with ‘over promise and under delivery’. Fraudulent Sub Agents often offer unrealistically good recruitment packages, with slim chance of actual migration, and attempt to earn an income by misleading potential migrants.

Transition from potential to current migrant enables migrants to realise the actual status of Sub Agents. Given that Sub Agents are informal stakeholders, migrants start to realise the former’s actual status through own experience. But this self-realisation requires one to go through the entire recruitment process and perhaps endure exploitation, abuse, vulnerability, lower incentives and wages, and lower probability to migrate. If this information can be provided earlier on in the recruitment process, potential migrants could be saved from adverse experiences in the recruitment process, and possibly ensured better outcomes in terms of wages, incentives and probability to migrate.

The findings of the study provide valuable information to shape proposed revisions to the SLBFE Act to regulate Sub Agents.