Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday, 6 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Ruvaiz Haniffa

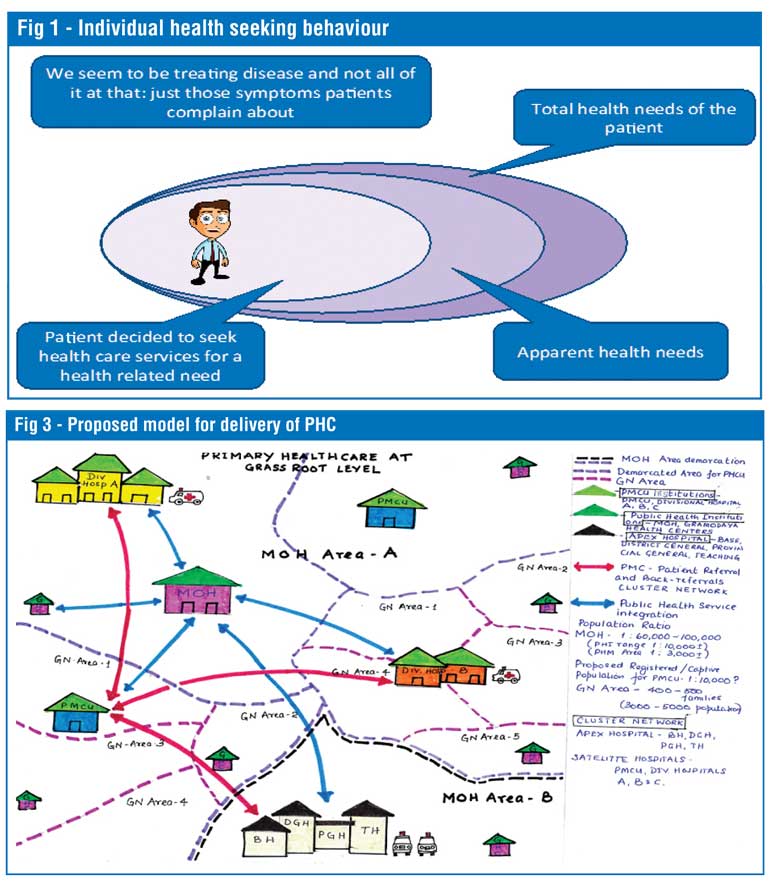

In today’s medical practice, the focus on the holistic or comprehensive care of the individual (as opposed to the patient) has become subservient to attempting to treat or manage illness in patients. The concept of preserving good health by incorporating and practising the preventive and curative aspects of medicine to achieve physical, mental and social wellbeing in individuals, families and communities by medical professionals adhering to the highest possible standards of professional ethical conduct seems to be a utopian ideal instead of a practical day-to-day reality.

There are numerous reasons for not being able to achieve this desired state but the problem is that over time Sri Lanka seems to be rapidly moving away from this ideal. We as doctors are forgetting why patients come to us. We are imposing our ‘superior’ knowledge and skills on patients more often than not in an unsolicited manner. In short, we have developed and come to accept as normal a system of doctor-centred care in which a medical condition or disease has become the fundamental issue requiring the doctor’s attention. We have lost the art of focusing on the holistic health needs of patients. A minuscule amount of these health needs will definitely require addressing medical conditions or diseases. This is why we need to shift our focus back to patients now more than ever.

I shall analyse the past and present of the Sri Lankan health system and attempt to answer the following questions and lay out a few proposals for change and how I see the Sri Lanka Medical Association’s (SLMA) role in such changes.

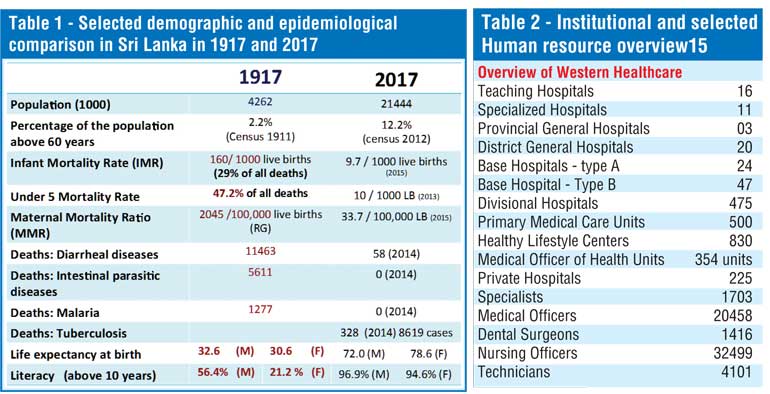

Sri Lanka over the past 100 years has transformed in terms of demography and epidemiology (Table 1). Sri Lanka has the highest aging population in the world and 1.7 million persons will be added to the elderly cohort during the next 15 years.

The relative contribution from mortality due to Non-Communicable Disease (NCD), which is currently very high (80.7%), is projected to remain high by 2030 (81.8%). Furthermore, 35% of Disease Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in Sri Lanka in 2015 was from three risk factors – poor diet, uncontrolled blood pressure and uncontrolled blood sugar - and more than 50% of the risk factors contributing towards DALYs in 2015 were found to be amenable to behaviour interventions or changes.

What this data shows is that risk factors which contribute to the highest morbidity and mortality in Sri Lanka are not disease-specific but are patient-specific, requiring patient-specific general measures rather than disease-specific interventions.

Sri Lanka is said to have a healthcare facility within 3.6 km of a household which delivers free healthcare at the point of delivery. The question we in the health system should be asking is what should these free healthcare facilties and the staff in them be doing to improve the individual or family and community health status in a rapidly-changing society with increased expectations of quality care in terms of personalised care.

Brief overview of healthcare system

Particular attention should be drawn to the 830 Healthy Lifestyle Centres, 500 Primary Care Units (PMCUs) and 354 Ministry of Health Units spread throughout Sri Lanka (Table 2). These are the points of delivery of Primary Ambulatory Curative and Primary Preventive Care. The Healthy Life Centres and PMCUs are severely underutilised due to the poor quality of care they currently offer leading to the ‘by-passing phenomenon’.

As summarised in Table 3, the State hospital-based Out-Patient Departments (OPD) accounted for 54,652,070 patient encounter episodes in 2015. The overwhelming majority of these visits were primary ambulatory curative care visits, which do not require secondary or tertiary hospital-based ambulatory care. In these settings the focus of attention should be the patients rather than the diseases in terms of screening for NCDs and treating minor health issues and referring patients to higher levels of care for ‘disease-specific’ health interventions and follow-up if needed.

Out of Pocket Expenditure (OOPE) on health

A comparison of Sri Lanka’s health status internationally is given in Table 4. Most of the health indicators are on par with developed countries. But what is alarming is that Sri Lanka is having a high OOPE on health (42.1%). This is of concern and given the demographic, epidemiological and health consumption or utilisation patterns, has the potential to push vulnerable sections of society into catastrophic health spending. This ironically is taking place in a State-sponsored healthcare system which is supposed to be free at the point of delivery!

According to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) of 2012/13, the average OOPE for health ranges from Rs. 213.88 to Rs. 7,323.68 with a mean of Rs. 1,488.28 per month for the total sample.

For households which incurred any health expenditure during the study period, the OOPE for health ranged from Rs. 609.16 to Rs. 9,419.44 with a mean of Rs. 2,557.03 per month.

Taking the OOPE per household as Rs. 1,488.28 per month, the total OOPE for Sri Lanka in 2012/2013 was Rs. 96 billion (excluding other indirect cost such as transport, cost of ‘bystanders’, etc.).

Analysis of the HIES in terms of specific disease and population groups is given in Table 5. It shows that if a household has a member suffering from a chronic disease who is elderly that household will have catastrophic health spending which is going to push them into poverty as a direct result of out-of-pocket health spending.

With an increasing elderly population and persons with NCDs, the average OOPE on health will show an exponential increase in the coming decades, further aggravating the problem of impoverishing healthcare.

In this context, has Sri Lanka got health system mechanisms in place to provide services to match the current and future healthcare consumption needs of our population?

In the seven decades since independence what we have done is:

More importantly in the seven decades since independence what we have not done is concentrate on the development of the Primary Ambulatory Curative Care Services both in terms of quantity and quality in both the state and private sectors.

A quick review shows that:

1.We have come to be very good at treating disease – eliminating polio, malaria and the control of communicable diseases to a point that these no longer are a major cause of mortality across the age groups.

2.We seem to be measuring the health status of our population based on the presence or absences of disease and infirmity – IMR, MMR, rates of hospital admission and number of ‘cases’ of a specific disease.

3.The number of disease-based health indicators we get are based on a number of patients who decide to seek ‘treatment’ from a healthcare facility geared to ‘treat’ illness (as opposed to facilities predominantly focused on preserving health while also treating ‘illness’) (Fig: 1)

4.We seem to have little emphasis on the ‘wellbeing’ of the population as a health indicator and even less emphasis on ‘taking care of the whole person’ in our healthcare system.

A conceptual framework for what needs to be done:

1. Need to shift from the concept of identifying, understanding and managing health from one of the ‘absence of diseases’ to one which identifies, understands and manages health from a perspective of ‘wellbeing’.

2. Need to shift from measuring disease as health to measuring wellbeing as health.

3. Need to address these health issues within and without the health system in a patient-centred manner.

The application, implementation and practice of Universal Health Care (UHC) in a sustainable manner within the Sri Lankan health system will allow today’s vision of shifting focus from diseases to patients to become tomorrow’s reality.

Role of a national medical association in this process:

1.Set up mechanisms to:

i.Address provision of UHC through patient-centred healthcare (Please see Fig 3)

nDevelopment of essential service package for primary – same healthcare at Primary Medical Care Unit (PMCU) settings for all

nDevelopment of technical guidelines for patient referral pathways for holistic healthcare – rational healthcare delivery guaranteeing Universal Health Care (UHC)

nDevelopment of staffing needs based on workload as opposed to staffing needs based on cadre requirements – guaranteeing quality care

ii. Create awareness and introduce healthcare innovations

nMake the shift from evidence generation to innovations and development in healthcare, setting up a Healthcare Innovations and Practices Hub (SLMA-HIPH) at the SLMA

2.Develop partnerships to increase access to healthcare

i.Between system – Primary, Secondary and Tertiary - and between Western and Traditional systems

ii.Between public and private sectors

3.Advocate at all levels for:

i.Patient centred, integrated healthcare delivery system

ii.Team based care addressing whole spectrum of patient needs

Through these developments the SLMA with other local and international partners envisage that the next decade or more in Sri Lankan health sector development will be dedicated to the development of Primary Ambulatory Curative Care.

We from the SLMA call upon all stakeholders to join us in calling on the Government to declare the next decade the ‘Decade of Primary Curative Care’.

(The writer is the SLMA President.)